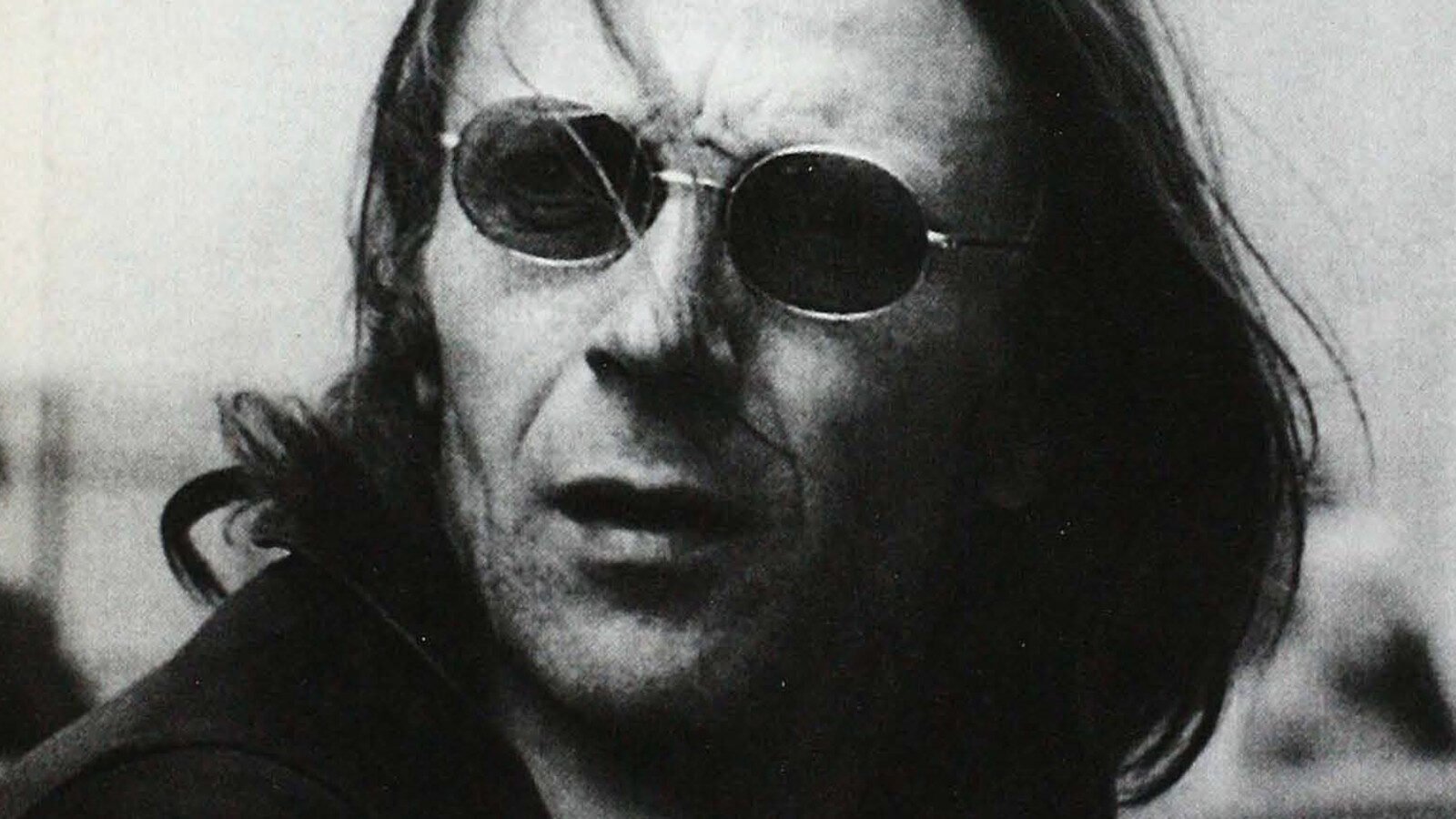

Blue Collar Dandy

I must have met Jean Eustache for the first time in 1962, at the office of Cahiers du Cinéma. I had the impression that he was the only person there who had absolutely nothing to do with movies. He would arrive every evening just before six to pick up his wife Jeanette, the magazine’s secretary, and would leave with her a few minutes later, all the while maintaining an air of the utmost discretion.

I must have met Jean Eustache for the first time in 1962, at the office of Cahiers du Cinéma. I had the impression that he was the only person there who had absolutely nothing to do with movies. He would arrive every evening just before six to pick up his wife Jeanette, the magazine’s secretary, and would leave with her a few minutes later, all the while maintaining an air of the utmost discretion.

So, a few months later, I was very surprised to hear that he’d just finished shooting a medium-length film called Les Mauvaises fréquentations (Bad Company, 63), which won two prizes at Evian’s 16mm Film Festival. Honestly, I was pretty wary of Eustache, and the sudden plunge into directing of “Jeanette’s husband,” this self-effacing prince consort, seemed strange, to put it mildly. In retrospect, I’m sure that his reserve at the Cahiers office was due to a certain timidity around the already illustrious Truffaut, Godard, Rivette, even Rohmer, the moving forces behind the magazine. But at the time, the unfavorable impression influenced my critical attitude toward Les Mauvaises fréquentations. The film was a fairly naturalistic depiction of a sentimental adventure that turns sordid at a dance in the Paris suburbs (in the town of Robinson, a few miles south of Paris—thus the film’s alternate title, Du côté de Robinson). “Vanity is but the surface” goes Pascal’s famous pronouncement—such was my first reaction to this movie centered around very mediocre people. But in the film’s favor were its rigor, its absence of easy effects, its observational exactitude, the precision of its soundtrack, and Eustache’s creation of a specific rhythm that seemed to coincide with everyday reality.

Eustache (the eu is not pronounced as in Eunice, but as in “writer,” with a silent e) would take a big step forward with Le Pére Noël a des yeux bleus (Father Christmas Has Blue Eyes, 66). It has the same devotion to reconstituting a natural ambiance, this time Narbonne in the southwest of France (one of Eustache’s two native territories, along with Pessac, near Bordeaux). The film had a provincial, slightly down-and-out, seedy quality, but it also had a certain warmth, Jean-Pierre Léaud’s peculiar dynamism, and a light, amusing touch. It also had a great finale in which the words “au bordel” (“To the brothel”) are repeated innumerable times, bringing to mind the final sequence of Vigo’s Zéro de conduite.

To see Eustache turning from fiction to documentary was surprising, especially since most filmmakers move in the opposite direction. But the line between documentary and fiction is a fine one. Fiction, for the most part, is based in the premeditated reproduction of something previously observed, whereas documentaries ostensibly observe the reality of the moment. The term “documentary” is in itself weak. For instance, in La Rosiére de Pessac (The Rosebush of Pessac, 68), Eustache gives us a sort of composite reality. He returns to his hometown and, with the mayor’s permission, films the election of the community’s most virtuous young woman. But the contest reveals the hypocrisies, incongruities and general ridiculousness that dominate such campaigns, obsolete in the infamous year of 1968, just before the events of May. La Rosiére de Pessac is a film that makes almost everyone laugh, but Eustache does nothing to influence the local politicians’ speeches or behavior: the Mayor’s pontifications, filled with massive blunders, become increasingly funny. Ironically, lacking the distance necessary for self-knowledge, the Mayor loved the film—he was far too much himself to judge himself sanely (a beautiful example of the ambivalence contained within the perception of reality, which allows each individual to appreciate a film for completely different reasons). The natural ambiguity of La Rosiére de Pessac is so much stronger and less artificial than any conceived by screenwriters. Eustache’s film is a triumph of unprompted deadpan humor.

The documentary option was also justified by economy: an hour-long film like La Rosiére de Pessac could be shot in two days, with no actors to pay. The small crew was not hired for the length of the shoot but paid according to actual time worked. The total cost was 35,000 francs, about $20,000 in today’s terms. As independent filmmakers rarely received funding from the French Government before May ’68, this was a solution for those who wanted to work. The film did good business: during its first two years in release, it earned more than three times its cost.

Eustache’s next documentary, Le Cochon (The Pig, 70), co-directed with Jean-Michel Barjol, was completed in an even shorter time: one day. It records a traditional practice that’s now almost vanished: the slaughter and butchering of a pig on a farm in the southern Massif Central. With scrupulous respect for popular traditions, the film features an amazing soundtrack in which the sound and originality of natural voices remains captivating, even though the thick patois and onomatopoeic accents make the actual spoken words incomprehensible.

Faced with the financial impossibility of mounting his autobiographical feature Mes petites amoureuses, Eustache made the two-hour Numéro zéro, also shot very quickly, and then decided not to show it a paradoxical attitude at a time when most filmmakers were fighting to gain the largest possible audience for their work. (He forbade me to look at the film even though I was its official producer, and told the programmers of the Tours Festival that he would allow them to show Pére Nöel only if they selected it sight unseen.)

Numéro zéro consists of a series of long, stationary takes in which Eustache’s grandmother tells her life story, rich in family conflicts and unusual events. I came to know this grandmother well, a deftly verbose, passionate character who feigned blindness in order to receive an invalid’s pension. Even though I was in a rush the first time I visited her place, I so enjoyed listening and learning from her that I stayed for a whole hour. Grandparents played an important role in the lives of many French filmmakers during this period. The generation born in the Twenties often sent their children to the countryside to live with their grandparents: this allowed the children to be better fed during the German Occupation, and the parents to enjoy life immediately after the war. The result was a reverence for grandparents and a rejection of the father and mother—a crisis that fertilized a number of artistic careers. Numéro zéro even inspired a television series about grandmothers. In 1980, for financial reasons, Eustache agreed to create a digest version of the film for broadcast, called Odette Robert.

Still blocked by French cinema’s economic system, Eustache spent many no long months writing La Maman et la putain (The Mother and the Whore, 73). He was obsessed by this autobiographical project, and constantly dreamt about it. In 1971, lacking funds and with nothing else to do, he offered to edit my film Une Aventure de Billy the Kid. In front of the Moviola, he would recite the dialogue he had written in his big notebook the night before, without pausing from his editing. The screenplay was a series of conversations (a bit like Rohmer), and he was trying it out on me, as he had on others, testing our reactions to the paradoxes formulated by his hero Alexandre, who would be incarnated by Jean-Pierre Léaud. What emerged was a sort of right-wing anarchism, not so far removed from that of Céline’s novels. It wasn’t inspired by ideology but by Eustache’s inherent need to provoke, and in the aftermath of 1968, right-wing anarchism was provocative indeed. It was also Eustache’s retaliation against the cinematographic system that had excluded him. The success of The Mother and The Whore probably rests on Léaud and Eustache’s need to make this improbable anti-conformist logorrhea work. But the film also captured the speech, and particularly the actions, of post’68 behavior, without sugarcoating. It could be said the movie’s strength lies in its insolent mixture of right-wing sentiments and sexual leftism.

The strength of the film also lies in its length (three hours and 40 minutes), even though nothing much happens in traditional dramatic terms. This was the moment of Rivette’s L’Amour fou (67), Kramer’s Milestones (75), and Oliveira’s Doomed Love (78), films that imposed themselves on spectators used to a never-ending supply of 90-minute product. In Eustache’s case, he held and renewed interest by alternating his main characters during the course of the film.

Long before shooting, Eustache asked me if I thought there might be a chance the film would be officially selected by the Cannes Film Festival. I said yes: of the three French films selected each year, there was often one that contrasted with the norm, representing a more unusual or experimental style of directing. Eustache always had Cannes in mind, and the jury wound up giving him (despite, but maybe because of, the scandal around the film) two important awards and international recognition.

Now the toast of the town, Eustache could revive his old project Mes petites amoureuses (My Little Love Affairs, 74). The story is set in his hometown, and seen through the eyes of a 13-year-old boy. Again, apparently a complete change of direction: after jumping from regionalist documentaries to the most auteurist Parisian fiction ever created, Eustache returned to the provincial chronicle, centered on a more or less average child. Four years before he actually shot the film, he told me he wanted to reconstruct his childhood: every wall section, every tree, every electric pole. According to Eustache, this was the only way to precisely render childhood impressions on film.

Mes petites amoureuses is very successful in the way that it brings certain French rituals to light—for Eustache, the very core of his work. In this case, it’s the rites of adolescent courtship: traditional places for flirtation during walks, the repertoire of romantic moves made by boys and girls, and the distances maintained between them, first kisses. Among the other French rituals faithfully recorded by Eustache: the disembowelment of a pig, the election of the Rosière, suburban dance parties (Les Mauvaises fréquentations), strolls down the streets of Narbonne (Le Pöre Noël), even café conversations in Paris’ sixth arrondisement (The Mother and The Whore).

Audiences were no doubt surprised and disappointed to find that the director of the scandalous Mother and the Whore had made an apparently harmless movie with a G rating. The commercial problem with Eustache was that there was never a way to stamp a superficial label on him. One minute he was the dandy from Saint Germain des Près, and the next he was a normal kid in the provinces. But he really was both in reverse succession. In the beginning, he was your standard young man, married and a father at 22, a manual laborer (first a railwayman, and later, when he was broke, a garment deliverer for my father), with no academic pedigree. He belonged to the productive breed of filmmakers without baccalaureates who came from proletarian backgrounds, along with Sacha Guitry, Francois Truffaut, Claude Berri and Frank Borzage.

Little by little, Eustache became a fixture in the fashionable Montparnasse bars, playing the horses, frequently getting drunk, forsaking his wife for new romantic escapades, all the while mixing with the film intelligentsia. He became a romantic artist, in the same sense as Rimbaud or Verlaine. The enclosed neighborhoods of Paris became almost a drug for him, and he started to feel uneasy anywhere else, unless he was shooting. He spurned sunlight for night shadows. He was bored to death and seemed helpless when he went to Rome or Athens, especially since he spoke only French. It’s hard to say now if this evolution was natural or not, or if it became a bit of a game of snobbism for him, to ape the “superior” classes. He was a surprising dichotomy of blue collar and dandy, a dichotomy that contributed to the development of his aesthetic. His experience of and respect for manual labor served him well when he worked as an editor, on his own films, Rivette’s or mine.

To come back to Mes petites amoureuses, one senses a willful sobriety in the actors’ manner and performance style, and the influence of Bresson. But Bresson is a dangerous master for his imitators. There is a principle of diction in his films that does not dramatize events but that, at the same time, has its own music, and that finally remains inimitable. And the very Bressonian principle of short scenes all of similar duration became monotonous over the course of two hours: once you got used to it, you knew where each episode was going to end. The film’s particular rhythm, among other things, explains its commercial failure. Shot on 35mm color stock (as opposed to the 16mm black-and-white of The Mother and the Whore), Mes petites amoureuses cost a lot more than its scandalous, marathon-length predecessor, and had only half as much an audience in France. Once again Eustache was forced to confine himself to medium-length films and shorts.

Une sale Histoire (A Dirty Story, 77) is a completely sordid episode of voyeurism, somewhat uncomfortable to watch, told in two very different ways, but using the same dialogue (a method later used by Hal Hartley in Flirt). It consists of a 35mm color film with a well-known actor (Michael Lonsdale) that plays like fiction, and an economically told black-and-white 16mm film with an amateur actor and a cinéma-vérité feel.

A new form of dichotomy and doubling back: a second Rosiére de Pessac (79), ten years after the first, coming after Une sale Histoire‘s twice-told story. Eustache seemed to be saying that plain old objective reality does not exist—that above all, the way we perceive can sometimes produce completely opposing meanings. In itself, the first Rosiére was already doubled: on the one hand an official election film that deeply pleased the Mayor/protagonist, on the other a virulent mockery of the same Mayor. The same “double” principle also operates in Eustache’s last two films, the 34-minute TV documentary Le Jardin des délices de Jérome Bosch (Jérome Bosch’s Garden of Delights, 80) and the short Les Photos d’Alix (80). In both cases, an aesthetic object, a Bosch painting or a series of photographs, each presented very precisely, coexists with an oblique viewpoint that at times seems completely at odds with what’s on screen. Alix Roubaud seems to be talking about the photos she’s looking at, but are the photos we’re shown the ones she’s speaking about? Eustache’s last films play a perpetual game with the viewer, who must struggle (in vain) to make sense out of what the director is concealing, and to determine whether it’s fiction or documentary. One can also speak of Eustache’s first films in these terms: the professional pickup artist who turns out to be a small-time petty thief; Léaud, who is viewed differently by people depending on whether or not he is dressed up as Santa Claus.

There has been a lot of speculation about Eustache’s suicide in 1981. Was it because cinema denied him? The motivation certainly was not economic, since on the day he died he had the equivalent of $10,000 in his bank account. Was it because he couldn’t make the feature films he wanted to make and was reduced to making shorts on assignment, films he made his own, but that few would see? That’s more plausible.

Lately in France there have been several suicides by filmmakers rejected by critics or by the system, or facing moral crises: Jean-Francois Adam, Hugues Burin des Rosiers, Christine Pascal, Claude Massot and Patrick Aurignac. Did Eustache think his death would attract attention to his work from viewers and critics? Such will always be the case, which became quite clear with the death of Truffaut, about whom many French critics had reservations, but who was loved by all once he was dead.

But Eustache’s main motivation was perhaps more profound. After leaving a screening of rushes from The Mother and the Whore, his old girlfriend was so shocked by his portrayal of her (as the “mother”) that she killed herself. It seems as though a kind of “suicide logic” was in the air: to see who would go the furthest, like the chicken run at the beginning of Rebel Without a Cause. Apparently Eustache had already tried to kill himself once before. Out of loneliness, he jumped from his window during a trip to Greece, which left him permanently handicapped. All of these things added to his overall melancholy. At 43, reduced to the existence of a bedridden videomaniac after a life in which he’d burned the candle at both ends, Eustache looked like he was 60.

Aside from Max Linder, a fellow native of Gascogne born eight miles from Pessac, Eustache was the only great French filmmaker to kill himself.

I might add that Eustache should be classified among his fellow filmmakers from the southwest of France, a very particular group that includes Catherine Breillat, André Téchiné, Jacques Nolot and Pascal Kané. Here are some characteristic traits:

- Sex, provocation and scandal are important in Eustache’s work (also note the sexualization of rugby in Nolot’s L’Arriére-pays, and the hardcore side of Breillat’s Romance, whose first film, Tapage Nocturne, has echoes of The Mother and The Whore).

- The affirmation of a pronounced individualism through the protagonist (a cinema of the “I,” where the main character is often the axis around which everything revolves), who is often in a state of personal crisis, and situated on the periphery of society.

- The presence of a child (Le Pére Nöel a des yeux bleus) or a teenager (Mes petites amoureuses).

- The description of provincial towns and landscapes (Pessac and Narbonne each figure in two Eustache films, and Le Cochon takes place in Les Cévennes, an area that is not part of Eustache’s family heritage).

This southwest cinematographic culture is little known, since the filmmakers who embody it mostly work in isolation from one another and don’t know each other well (apart from Téchiné and Nolot). They don’t form a group or a school—their fierce individualism won’t allow it. But regional French film expression is more prominent now than the Marseillaise school, which owed its renown to the niche opened up by the distinctly folkloric Marcel Pagnol.

There are other reference points for Jean Eustache’s films, including John Cassavetes (The Mother and the Whore is not far from Faces) and especially Maurice Pialat, whom Eustache admired. There are a number of resemblances, in terms of both subject and execution, between Mes petites amoureuses and L’Enfance nue, Pialat’s first feature. It’s not by chance that Pialat plays a small part in the Eustache film.

Two excessive, short-tempered, fiery filmmakers, who distinguished themselves by their rejection of big, complex dramatic constructions and exploitative situations, by their keen observation of human behavior, and by a certain dislike of plasticity.