I love everything that flows, everything that has time in it and becoming, that brings us back to the beginning where there is never end.

—Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer

Benh Zeitlin has a thing for water. As a child, he recalls, he was always more interested in sea lore and stories set at the bottom of the ocean than those that took place on dry land or in the furthest reaches of the galaxy. His 2005 short, Egg, was nothing less than a stop-motion animated take on the greatest of all seafaring tales, Moby Dick, set entirely within the shell of the titular protein. It was followed in 2008 by the live-action Glory at Sea, a lyrical paean to post-Katrina Louisiana in which the victims of an unspecified storm linger in an aquatic limbo while their families set out to find them in a raft cobbled together from a bed, a bathtub, and a rusted-out car. And now there is Zeitlin’s first feature, Beasts of the Southern Wild, which returns to bayou country to tell an even more richly imagined tale of stubbornness and survival in the face of Mother Nature and Uncle Sam. Earlier this year, it won the Grand Jury prize at Sundance, where it was easily among the most audacious such debuts in the almost quarter-century since sex, lies, and videotape.

“In New Orleans, water is like a god, like a Greek god that controls everything down here, and your life is in the balance of the waterways,” Zeitlin says between mouthfuls of rabbit-and-sausage jambalaya on a recent afternoon at Coop’s Place, an unpretentious bar in the city’s venerable French Quarter. “It’s one of the things that attracted me to this place, how visceral your relationship with nature is, and particularly water. I’m making these films about people who are in a state of chaos and trying to get their bearings. So that feels like the proper surface for the type of stories I want to tell. They don’t make as much sense if you’re standing on solid land. You kind of have to be unmoored.”

Zeitlin remembers first visiting New Orleans on a family vacation at age 13 and feeling quickly seduced by the city’s mythopoetic airs—unsurprising for the son of two professional folklorists who says he’s always had “this desire to kind of invent my own reality.” He returned in 2004 on a road trip with friends from Wesleyan University, where he studied film and founded his Court 13 production company (named for an abandoned squash court), and again in 2007 to make Glory at Sea.

In between, he fled to Europe, where he worked for a while with Czech director Jan Svankmajer and toyed with the idea for a short film about people living—or hovering somewhere between life and death—underwater. He thought he might make the movie with friends on a Greek island—a longed-for reprieve from the painstaking, solitary experience of animation. Then two things happened. First came a kind of epiphany. “I was working with these expat filmmakers and I had this moment of realization that I didn’t want to be an expat. I wanted to make American movies. I wanted to go back and find a way to make this in the States,” he says. Next came Hurricane Katrina, and “the fundamental idea of the movie just kind of hooked in with that. Here’s where this is actually an important story.”

So Zeitlin decamped for the Crescent City, where a friend offered him lodging in a habitable section of his hurricane-gutted home, and began rewriting, eventually transforming his idea for a “five-minute, abstract artsy short” into the 25-minute Glory. Much like the jerry-built raft at the center of the story, he shot the film piece by piece over six months, largely on open water, and with the invaluable kindness of many friends and strangers. (As he would later for Beasts, he also co-composed the film’s stirring, strings-and-squeezebox musical score with collaborator Dan Romer. One track, entitled “Elysian Fields,” was eventually repurposed by the Obama campaign for a series of television ads.) By the end, he says, “My world had gotten so big. It was such an amazing experience making that movie, and it never could have been done anywhere else. I thought, as opposed to the animation I was doing before, this is the way I want to work, and it can only happen here.”

The film traveled widely on the festival circuit, winning prizes in South By Southwest, CineVegas, and Woodstock among others, and leaving Zeitlin with a harrowing survival story of his own. In the wee hours of the morning of Glory’s SXSW premiere, while driving from New Orleans to Austin with the finished film, Zeitlin was rear-ended by a drunk driver—a near-fatal accident that shattered his hip and pelvis and left him unable to walk for six months.

While recuperating, Zeitlin began to think about his next project, which he hoped to adapt from the work of his friend Lucy Alibar, a Florida playwright whom Zeitlin first met in a summer playwriting camp when they were both teenagers. At the same time, he found himself compelled by “the need to tell a story about why people stay here,” he says in reference to the many Louisiana locals who refused to evacuate when Katrina rolled in, and those who did leave only to return and rebuild on precarious land. Then the two ideas organically fused in Zeitlin’s mind. “There was this particular play of Lucy’s”—Juicy and Delicious—“about when her father was diagnosed with cancer and her feeling that the world was coming to an end, and it was kind of just the key that unlocked the question I was trying to address about why people stay. I think it was hard for people, people who don’t know this city and this region, to understand how deep the roots go and how impossible it is to transplant what’s here to somewhere else. It’s like a parent, and so that was the thread that we hit on and thought, Oh, okay, this is the story of being the child of this very brutal, dangerous thing that gets sick and you have to survive, and how do you survive that and why do you stand by that and what’s the right thing to do in those circumstances?”

So Zeitlin and Alibar took characters and situations from the play and deposited them into what feels very much like an enlargement of Glory at Sea’s post-diluvian universe—a ramshackle community of homespun eccentrics living in a fictional floodplain known euphemistically as “The Bathtub.” At its center is one of the more remarkable protagonists to front an American movie in recent memory—an intrepid 6-year-old named Hushpuppy who, as all children are wont to do, tries to make sense of the world around her, even as it is quite literally giving way beneath her feet. Living with her feral, tough-love father, Wink, on a makeshift estate comprised of two trailers and some oil drums, Hushpuppy (who also serves as the film’s first-person narrator) envisions herself as the heroine of her own epic monomyth, one in which the supreme ordeal of Katrina gives way to a series of battles against encroaching government evacuators, a father she knows is dying, and primordial creatures called “aurochs,” which are loosed from the polar ice caps during the storm.

“When I first came here a year after the storm, it was a totally surreal place,” says Zeitlin, who credits the phantasmagoric films of Emir Kusturica with inspiring him to become a filmmaker. “It seemed just like Biblical apocalypse, and whether or not that was every individual experience, it was important to me to kind of elevate the story, as I did with Glory, to the level of a myth or a folktale. Look, the politics of any event is always incredibly divisive: ‘It was all Bush’s fault.’ Or: ‘It was the local government.’ Black people. White people. None of which actually gets at the real tragedy or the real emotion of the event. To me, that’s sort of the purpose of myth and folklore, to be able to talk as an entire culture about something. So we have the story of the West, and there’s this cowboy, and we can revise the story of the cowboy depending on how we want to interpret our culture.”

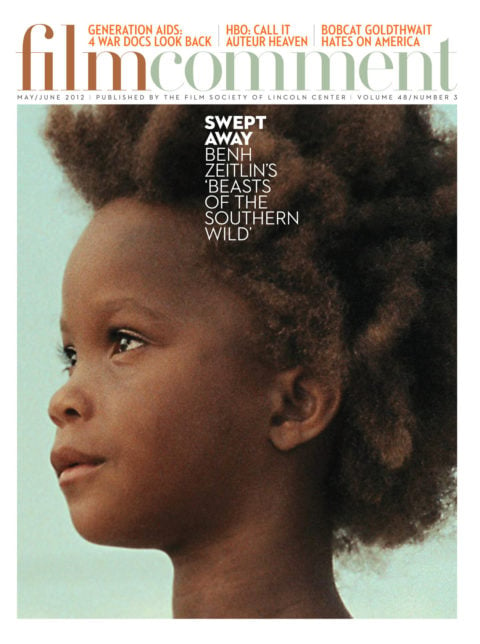

Initially Zeitlin and Alibar imagined that, given Hushpuppy’s age, the film would inevitably take on a somewhat comical, cutesy tone. That was before they met their muse—and their match—in the form of kindergartner Quvenzhané Wallis. All of 5 years old when she auditioned, the New Orleans local immediately blew the filmmakers away with her ability to channel the character’s operatic emotional journey in no uncertain terms. The result is a performance as impressive as any you are likely to find by any actor of any age in any movie this year.

Zeitlin recalls a moment in the casting process, after Wallis had been chosen and was now reading against actors auditioning for the role of her father (a part eventually played by the formidable Dwight Henry, whom the filmmakers knew from his Seventh Ward bakery, The Buttermilk Drop). In some of the auditions, the young actress would simply shut down emotionally and be unable to perform. “I talked to her mom and she said, ‘Why don’t you just take her somewhere and talk to her like an adult. She can handle it.’ I think she was still 5 at this point,” Zeitlin says. “So I went to her and said, ‘What’s going on right now?’ And she said, ‘You know, sometimes I can snap it, but today, with this guy, I just can’t snap it. Something’s wrong. Something feels off.’ And I realized that she had an internal sense of when she had nailed something, which is rare even in a professional actor. She wouldn’t always admit it, but she always knew when she’d gone there and when she’d gotten it. And she would get annoyed at me when she knew she’d gotten it and I would want another take. She just has that internal mechanism which is really rare, and to find it in someone that young was such a miracle.”

As with Glory at Sea, the production of the movie once again resembled a massive community art project, guided by Zeitlin’s abiding belief that anyone, regardless of professional experience, can contribute to the making of a film. “There’s so many facets that you can really bring everyone you know together, who you care about, who’s talented, who has a good heart, and they can find their way into creating something good for the movie, provided you allow for the individuals working on the film to have agency and to be able to express themselves, which I think is the hardest thing about when you go to work on a traditional set,” he says. “The creative hierarchy is incredibly regimented and the people actually touching the stuff that ends up on screen don’t have any love for the things that they’re making. Even if the designer does, by the time it gets to the person actually painting that or sewing it together, there’s no feeling in that actual task.”

Zeitlin’s goal, he says, is to create, for an alchemical moment, “a world that has its own story that it’s telling and its own story that happens internally”—in short, to make life imitate art and vice versa. So when the director recruited his artist sister to design Hushpuppy and Wink’s home, he asked her to live in the set as she was building it, and to use only those materials that could be found on the surrounding land. “You never see all the stuff that’s in that house when you watch the film, but you do sense that there’s a logic behind it, because it’s lived-in,” he says. “The movie is sort of pushing past realism all the time into this hyper-real place or this fantasy place, but because all the pieces are so organically found and every element is built so organically, I think it sort of keeps it in realism in this way that is really important, so that it doesn’t drift away from what people can relate to.”

Likewise, he encouraged his largely nonprofessional cast to incorporate aspects from their own lives into the characters they were creating, borrowing a page from the playbooks of Mike Leigh and John Cassavetes, whom Zeitlin calls two of his idols. “You want to preserve the essence of the people who are playing the parts, even though they’re not playing themselves,” he says. “We would rehearse the scenes and they wouldn’t come out right, so we’d pull away the script and have them improvise it, and then we’d rewrite it to what felt natural coming out of their mouths. For Dwight, who plays Wink, we did hours and hours of interviews about his life, then went through the script and attached each scene to some moment from his life. You revise towards the people, because they are the ones who are bringing this to life, and they taught me a tremendous amount about who the characters were and how the story played out.”

There’s certainly no mistaking the love and handcrafted detail that have gone into each and every frame of Beasts—love for things that flow, for those washed away by the historical tide, and above all for the people of New Orleans and its surroundings, which have been too often reduced by movies to a pile of hoary clichés about black magic and magical negroes. (For recent examples see The Princess and the Frog and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.) As day gives way to night and Zeitlin and I segue to BJ’s, a Ninth Ward watering hole with cheap beer and friendly service, we’re joined by producers Dan Janvey, Josh Penn, and Michael Gottwald, who along with Zeitlin’s sister comprise the rest of what could be considered the Court 13 inner circle. (After that, says Zeitlin, is a concentric ring of about two dozen people who are “involved in every project and whose individual stuff is related to what we do.”) All, like Zeitlin himself, are New Yorkers who now count the city as their full- or part-time home and are committed to developing a thriving film culture there.

“This town is full of film at this point, but none of it is organic to the city,” says Zeitlin, referring to the numerous recent Hollywood productions (including Déjà Vu and 21 Jump Street) that have taken advantage of Louisiana’s generous tax incentives. “New Orleans pretty much expresses itself through music and parade culture, and I think it would be amazing if people were expressing themselves with the camera. No one would ever have seen anything like what would come out of this place if there was a real film culture here.”

Before they shut it down to focus on the making of Beasts, the Court 13ers had even developed a community education program, offering afterschool filmmaking classes to grade-school students. And looking toward the future, Zeitlin envisions a day when Court 13—like a progressive socialist version of George Lucas’s Skywalker empire—might be a nexus of local film production, offering their casting and visual effects services, and the unique ethos behind them, for hire to all interested parties. First, though, they’ll have to rent office space. Indeed, for the present moment, the Court 13 mentality is quite literally a state of mind.

“It is a collective and we really want it to be seen that way so we can protect the method, and we’re working very hard to figure out how to continue growing the operation and tell bigger stories and make bigger movies but to not kill this thing that is the reason why the films are so good,” stresses Zeitlin. “Which I think has everything to do with the way they’re made.”

And this much is for sure: Zeitlin won’t be trading the Gulf Coast for the West Coast anytime soon. “I think there’s a failure to recognize that all movies, like all art, emerge from a culture,” he says as he downs a glass of a local brew. “There’s this sense that Hollywood is a culture-less place, but it is a culture. Not that I don’t love Hollywood movies, but it’s as if you only listened to music that comes from one city, or only looked at art that was painted in Chicago. Why would you do that? So I think it’s an important thing for movies everywhere, but especially in America, to come from different places.

“I’ve had people ask me, ‘So, are you coming to L.A.?’ And when I tell them I’m not, they say, ‘So, is that your sort of fuck you to the world?’ Well, no. Is you living in L.A. your fuck you to New Orleans? I like to live here, and I think it’s important to put your life before your career. That’s certainly a mentality down here. There’s people I know here who I still have no idea what they do during the day. No one asks you what you do here, which is great.”