Apropos de Cannes

Strange show, this XVIth Cannes Film Festival, with its films full of noise and fury, replete with heroes who only seldom were triumphant, and solitary people full of anxiety beaten in advance before they even started to live. A phantom stalked the Croisette—the phantom of television. Wide-screen producers, stammering with terror, looked for a Holy Alliance against the brazen small-screen intruder; against automobiles used for weekend escapes; against fair weather reports—all of which conspired against their box office receipts.

The festival began with a film shown out of competition, The Birds, by Hitchcock, a work recognizable as such even without the screen credits by the pasteurized beauty of his heroines: the praying-mantis type, frustrated by her natural incapacity for satisfaction, the abusive mothers, the underlying puritan morality, the desperate wish to scare. From the all too facile pyrotechnics of Psycho to the grotesque fable of these birds who, “enraged” by a century of carnage on the part of mankind, begin to practice a kind of Malthusian revenge with the help of their sharp beaks, gobbling up eyes and other delights, the downward curve of Mr. Hitchcock’s career continues. Terror is a delightful mistress but one which can be appeased only with thrills a thousand times more subtle than what we are vouchsafed here. The back-screen projections are simply unacceptable. What remains? A few good scenes such as that in which the heroine, seeking shelter in a telephone booth with fragile window panes, suffers the organized attack of a hundred birds in full fury.

With The Conjugal Bed, Italian Marco Ferreri, swims with abrupt strokes in the black waters of a very personal sense of humor. The story of this Roman virgin with the face of an angel, Marina Vlady, who marries and exhausts her elderly husband with the single goal of procreation, is told in sequences that are often quite successful, sometimes heavy, but always ferocious. The Conjugal Bed seems to have had problems with the Italian censor—understandable if one considers, for instance, the scene of the adoration of an embalmed Madonna who, through a miracle, grows an impressive beard to discourage the ardor of two would-be violators.

A scandal broke. The Syndicate of Producers protested the official choice made by France, The Depths, a beautiful film by Nico Papatakis after an original script by Jean Vauthier. It was accused of being detrimental to the prestige of French cinema. But the satisfaction of this same syndicate with two other French films made one wonder. Carom Shots by Marcel Bluwal is a triumph of vulgarity, an exasperating anthology of mediocre photography and dialogue of the lowest rung. And Rat Trap is non-directed by Gabriel Albicocco, non-acted by Marie Laforet, badly acted by Charles Aznavour, all done in “South American” sets whose falseness is such that despite everything it must have required a certain talent. Returning to The Depths, the stupidity of the attacks against it was so evident that by a reverse reaction it attracted the well-wishing interest of the public, which otherwise might have been indifferent. But well-wishing or indifference are not adequate reactions to the paroxysmic work so continuously sustained by Papatakis and the amazing portrayal of hysteria by the Berge sisters, who were entitled to their share of prizes.

The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock, 1963)

Three “sacred monsters”—Robert Aldrich, Joan Crawford, and Bette Davis—compete with each other in the bargain-basement sadism of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?. The promising ferocity of the film’s beginning subsides very quickly, leaving a tale completely sans nuances, neither in the psychology of its characters nor in the development of the situations. Crawford and Davis are pitiful in their roles as two sisters, one an invalid-martyr, mistreated by the other, a drunken, jealous, half-mad harpy, responsible, it seems, for the accident that crippled the other. (Later we see that what seems to be is not necessarily so, since an incredible reversal takes place.)

After The Cassandra Cat, an affecting little Czech fable on the dangers of bureaucracy, selfishness, and meanness, came the surprising Lord of the Flies, a British film by Peter Brook—his best thus far—after the novel by William Golding. The metamorphosis of a group of British schoolboys into a savage gang, following their shipwreck on a tropic island (a shipwreck from which not a single adult survives) is delineated in vivid images helped by a faultless rhythm in the cutting. The public, delighted in the beginning with what seemed to be an English counterpart to War of the Buttons, cooled off visibly when cruelty, including a hardly disguised cannibalism and all the other manifestations of jungle law, began to make its appearance on the screen, smothering the lovely legends of childhood innocence. A good film, unjustly awarded no prize.

The Venerable Ones, a discreet and tormented work by the Argentine Manuel Antin, was up against an almost complete lack of communication with the audience. It is not a successful film, but frequently it is an “inhabited” film. Some real people live in it. Halfway between the world we call real and its dream counterpart, which invariably turns into a nightmare, is the story of a rather dim group of small people who try to find in exaggeration and lies the hope for a reason to live. A lack of rigor in the direction of the actors is ultimately detrimental to the total quality of the film.

Codine, made in Rumania by Henri Colpi, after a work by Panait Istrati, is heavy going except for the beauty of some shots which sink back immediately into the déjà vu.

Harakari, by the Japanese Masaki Kobayashi, tells the story of a strange vengeance in an agonizing frame of the feudal period. Its images are often very beautiful; the camera, gliding with the grace of a geisha, maintains a constant fluidity. Alas, all this is interspersed with unthinkable harakaris, some performed with a wooden knife! Not advisable for any spectator not fond of vampirism.

For Those Who Will Follow, a Canadian film by Perrault and Brault, is an example of the new cinema verité. It is a boring evocation of the life of peasant-fishermen on the Isle of Coudres. If truth has no boundaries, this time it has fallen to the bottom of a bottomless well where few fish swim.

The Fiancés by Ermanno Olmi is a touching Italian film. It relates the death of a love affair succumbed to the ravages of a too prolonged betrothal, and its resurrection through a mutual understanding suddenly arrived at by the couple. The action takes place in Lombardy and the South of Italy and is full of anecdotes of a rare sensitivity.

Harakiri (Masaki Kobayashi, 1962)

Coming from Hong Kong, the incredible Empress Wu Tse-Tien by Li Han-Hsiang has all the commonplaces of pure melodrama without any of its charms. It pretends to recount the exploits of the Empress Wu Tse-Tien, who, with a soul of ebony, reigned, schemed, intrigued, and killed with infinite grace, sometime during the Chou dynasty. In the incoherence of this tale the spectator is plunged into an abyss of perplexity—all this in faded images.

Nothing is simpler than to follow the effects of This Sporting Life, an English film by Lindsay Anderson. It’s the story of an ex-miner who has become a professional rugby player and of his landlady, a widow suffering from a perpetual neurosis and haunted by the memory of her husband’s suicide. All this is done with a zest for homosexuality, a few drops of misogyny, a basket of broken noses, many broken teeth, and spiders killed with the blow of a fist on a white hospital wall. Richard Harris gives an unconscious imitation of Marlon Brando and Paul Newman. Almost a good film—too bad.

How to Be Loved, a Polish film by Wojciech Has, is the story of a failure. It is about an actress who, during the occupation, hides a young colleague for whom the Gestapo is searching, and with whom she is very much in love. She finds out too late however, that those perfumed paradises, “where all those we love are worthy of being loved,” are far away. Drifting lives, fiascos, the color of emptiness—all this lacks unity; and the acting leaves much to be desired, especially in the close-ups which do not forgive certain gestures meant to be expressive of emotion.

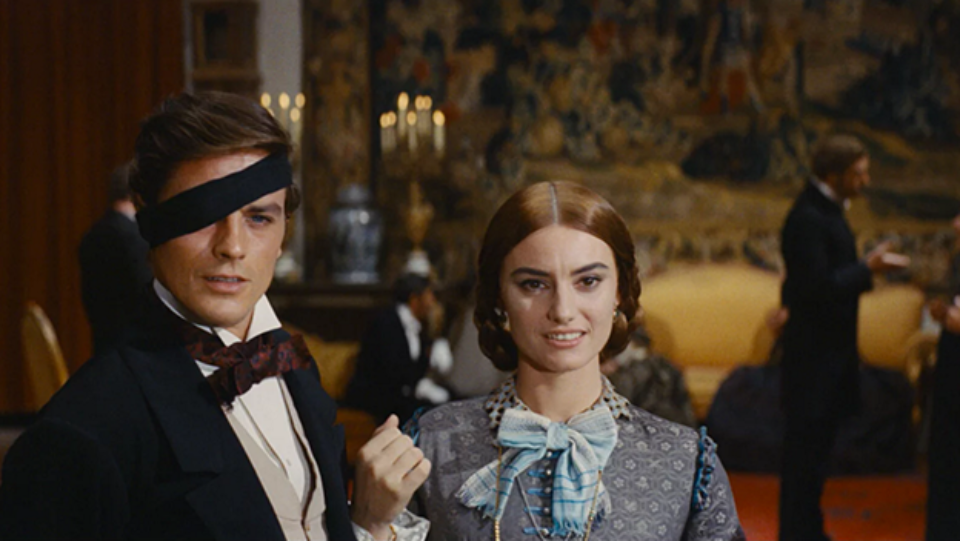

The showing of the German Alvorada, a masterpiece of stupidity, makes one wonder about the mysterious criteria for the selection of films here. Suddenly, as if to make up for it, came the overwhelming appearance of The Leopard by Luchino Visconti, from the novel by Lampedusa. It was, without reservations, the only dazzler at the festival. Absolute mastery of direction, the splendid beauty of the images, the sure direction of the actors—everything makes the three hours and twenty minutes of projection glide by as if by enchantment. Burt Lancaster, who a priori did not seem to be the ideal Prince of Salina, portrays beautifully his part of a lucid aristocrat trying to adapt to the irreversible forces of social change. It won, undisputed, the Palme d’Or and, by the way, was the only prize winner to obtain an award without opposition.

The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963)

Optimistic Tragedy, a Soviet film by Samson Samsonov, would be of an exasperating academicianism if it were not so grotesque. It tells of the Bolshevik struggle against the anarchists in the beginning of the Revolution. Just as surprising, but in a different sense, is the absolute freedom of delirium in El Otro Cristóbal, made in Cuba by Armand Gatti. The fight put up against Anastasio (a dictator who succeeded in taking over the sky by a coup d’état and now wants to suppress the little village of T— which was responsible for his death) by the sailor Cristóbal, as the head of the villagers, serves as a background for one of the maddest enterprises in the entire history of the motion picture. It is incredible that this kind of work should still be made. The film is uneven, as they say, the best and worst side by side in absolute freedom. But the best parts justify this work which resembles nothing else and which is surrounded by a musical orgy of very great beauty.

The last film shown at the festival was Fellini’s 8½, out of competition. As always with this director, we were treated to a double play of foxiness and sincerity. Hell, little audacities—salute to the Left, wink to the Church, kneel to the Right. Spangles of gold-dust powder in your eyes and into your soul. It appeared that it had some partisans.

The announcement of prizes was accompanied by cries and boos of protest from the public, except for the unanimity of opinion about The Leopard. How was it possible to include in one and the same special prize of the jury both Harakari and The Cassandra Cat? In the name of what diplomacy were Marina Vlady and Richard Harris given the prizes for the best actors? The prize for the “revolutionary epic,” invented for the occasion, was given, naturally, to Optimistic Tragedy; the prize for the film “having best exalted human solidarity” went to To Kill a Mockingbird; the award for the best scenario went to Codine, an adaptation of a novel.

The festival had its positive side, in allowing us to see The Leopard, Harakari, The Lord of the Flies, The Fiancés, El Otro Cristóbal, The Depths and the films of the special week organized by the critics, notably that jolly monument to mad humor, Hallelujah the Hills, by the young American director, Adolfas Mekas.

No matter if the rest was silence.

Translated from the French by Herman G. Weinberg