And His Ship Sails On: Federico Fellini

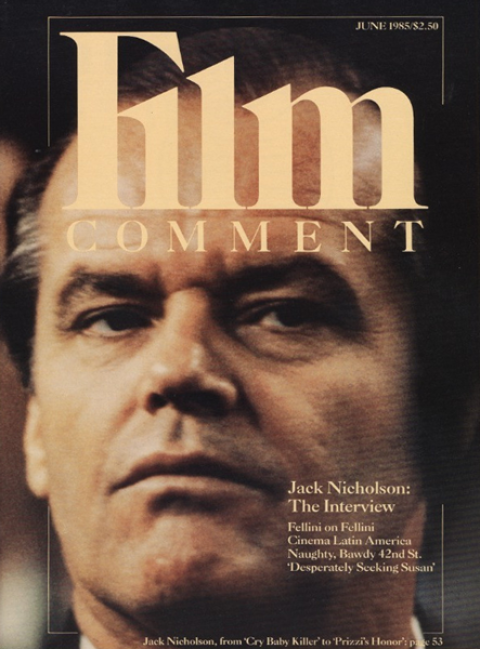

To celebrate the upcoming 50th Anniversary of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Film Comment will be making some classic pieces from our archive available online. This week, read Gideon Bachmann’s conversation with the Italian master, FSLC’s 1985 Chaplin Award Gala honoree.

The Italians say, “History isn’t made, it is told.” And they are the best proof that we invent not only our past but our present as well. Otherwise there would have been no Renaissance and none of that miraculous life-force continuity surviving the proverbial and perennial crises which, as Boswells from Goethe to Barzini have observed, Italians thrive on.

Only a foreigner finds it funny, therefore, to repeat the old saying that Federico Fellini invented the Via Veneto and that the Italians have tried to live it ever since. In Italy, it is not just a saying, it is the truth. And much more has come from Fellini; things that not only the Italians are living. He has, in fact, changed our landscape.

Of course, “invent” isn’t really the proper verb. It’s that suddenly things are concrete that we’ve always known but couldn’t express. He confirms us. We often say, “Isn’t it just like out of a Fellini film?” A far cry from the days when in a film we used to exclaim, “That’s so natural!” The Fellini vision has become an integral part of the language we use to deal with reality.

I project myself into a future century and imagine looking back on this one, bemoaning the demise of its art as today we bemoan the passing of that of the 15th, extolling in the same breath its outstanding practitioners. Isn’t it Fellini’s you would mention first when asked for names that might remain as our century’s prime artists, just as it is Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s when thinking of the Renaissance?

Fellini has outlasted the critics who said he was neither concerned with sociology nor politics and we now live in an age marked by a renewed faith in art as fantasy. Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Every film is a documentary” is quaint in a world thickly smeared with a layer of TV sets hourly proving every documentary to be a fiction. How quick we were to deride Fellini, then 30 years ahead of his time for “fictionalizing reality” at a time when neorealism, in its heyday, hid its artifice in folklore. Fellini shortened our road to a deeper understanding of the nature of media. He has reversed the maxim that life, like history, when told, becomes fiction. His fiction, when told, when seen, becomes life.

His method is essentially the application of the poetic principle to a Cartesian form. Refusing the camera’s basic limitation—that it photographs things that are put in front of it and tends to create works which Maya Deren used to call “pre-cameratic” (Dreyer, Chaplin, Bergman, Welles, and Renoir all work like that)—Fellini has, in the simplest terms, made it into a paintbrush. He is the only one among commercial directors faithful to the traditions of the avant-garde, surrealism, experimental, and the total predominance of the personal. Every shot, every frame, every costume, every design, every movement, and every sound are part of a larger-than-life vision, a burst of heart arousing in our innermost plexus a releasing shout of recognition.

That is why Fellini’s seas are made of identifiably plastic sheets, why his Via Veneto was built into the studio, why he is the protagonist of all his works, why his women have those bosoms, those thighs, why he was able to make 8½ the male’s Golgotha in the era of productivity, and Casanova the artist’s search for love. It is also the source of his anguish and despair, his sense of age, his fear of rejection. The cinema is a trapeze act—put your soul on the line and flip it high in the air for the millions to cheer or jeer. No net for a heavy fall. Fellini has risked it again and again, sometimes missing. But sometimes he didn’t, and those times make the entire experience of cinema worthwhile.

Amarcord (1973)

You love to tell stories. Where do they come from? What fascinates you most?

The stories are born in my memories, my dreams, in what I imagine and fantasize; it’s a very natural and spontaneous birth. I don’t specifically sit down to invent something. It’s a series of suggestions of the mind, thinking about things read, personal experiences lived, coming together with a pretext of some sort, a stimulus of the moment, such as the face of a man in the subway, the smell of a waft of perfume that passes, a sound I hear—something that evokes those fantasies and persons and situations that I have in me, and which almost by themselves organize into a form, provided I give them freedom and follow them on their path. It’s a matter of staying with them for a while, of making friends with them.

And the urge to tell them, to pass them on, these stories, where does that originate?

That is not really a question I have asked myself, nor does it interest me particularly to do so. I think that I had decided very early what my work in life would be, what my life and my road would be, it seemed to me that I had identified my itinerary, that I had understood that this was going to be my destiny: to tell stories. Why I decided this instead of becoming a priest or a circus clown—although in a certain sense I am doing both of those things—I cannot tell now. But I remember that in school most of my companions had very clear ideas of what they wanted to be. One of them was sure that he would become an admiral, and he did, in fact, succeed. Their ideas seemed most precise, they knew how they were going to organize their lives. I only knew what I wasn’t going to do. I wasn’t going to do any of the things that my school companions thought they were going to do. I knew I wasn’t going to be a lawyer—which is what my father wanted—or a chaplain—my mother’s wish—and I surely wasn’t going to be an engineer, like my best friend.

In fact, I was a bit confused about what my career was going to be. I thought about being an actor or a journalist, a writer or a painter, a marionette artist, a singer… and with all these both similar and contradictory choices I couldn’t decide after all. Today it seems to me that I am in a profession that unites, more or less, all these various possibilities. A film director is a painter, a journalist, a sculptor, an actor. Anyway, I think that my occupation doesn’t contradict any of those early ideas.

A journalist chronicles that which already exists or occurs, while you probe deeper into characters, further than they themselves might know. What is it, then, that lights in you that first spark of interest?

Usually it’s something that surprises or strikes me, or arouses my compassion, or makes me smile. I suppose you could say it’s the way human creatures express themselves, in all their myriad ways, with all the components and connotations of behavior. Sometimes it can just be something a person wears that can suggest a fantasy about him to me. It’s hard to say exactly.

It seems to me, too, that the way a story evolves often has nothing to do with a character, or at least is not directly inspired by a character but perhaps by an atmosphere. I may be exaggerating when I say it could be a waft of perfume, but actually that could be, because all it takes is a re-evocation of something that already is, that already exists in me. Or, if it is something that exists outside of me, there is an evocation of something that reveals some aspects of its interior, of its own completeness. It is often through such a form of revelation that I seem to be able to penetrate into the interior of things.

It’s really like seeing, far away in the night, a spark of light, and as you approach you find that it is a light in the window of a house in a street in a town, where people live, where there are other streets, where there are piazzas… and as the string unravels you slowly lay bare a whole map of places, characters, sentiments, and situations.

Your films actually often end with a spark of light in the distance. What interests you most: that which has already occurred—the past, memories, and nostalgia—or that which is still to happen, that toward which the people you have laid bare are moving?

I don’t have a good answer to that, I have no precise system. Beyond recognizing in myself an incurable tendency to imagine a story and to invent situations, every film has its own liturgy, makes its own demands on you, requires its own approach. It’s like a friendship, like human relationships, like love: there are no rules, and they are born from many different sources.

What I can say, however, is that I seem to have met all my films in the most natural way, as if they were already in me, like a train that runs along a fixed track along which there are, waiting and ready for it, the stations of the various places where it is meant to stop. When I look back now, on the films I have made, it seems to me that rather than having made them myself, they had already been there, waiting for me, and that my work consisted mostly in the effort of not deviating from that fixed track, to faithfully and punctually follow that itinerary, that sketched road, and to find them there.

But you shouldn’t listen to me too closely, because in interviews one always tells a lot of nonsense, trying to express a dimension between philosophy and romance, whereas in reality things are much more simple.

When you first perceive that spark of light in the darkness, what attracts you to it? Is it physical? Metaphorical? Intellectual?

I can only talk within the limits of what I do; I don’t want to sound like Dante Alighieri… but the sign of a first contact having occurred, of being close to that still hidden and closed town, the thing that in the end will be the film, comes to me from a feeling of joy. It’s like a pleasant tickle that runs through your entire organism. That sometimes unexpected feeling of good humor and of joyfulness is like a first greeting addressed to me by this new thing, a sign of recognition of a story already beginning to grow, a hint of greater precision about to occur.

So it is like the encounter with a woman, someone you see fleetingly in the street, you feel a first vague attraction, and then develop the relationship in your fantasy…

Perfect comparison. Woman is in fact that part of yourself that you do not know, and thus you project upon her while you are waiting to reveal yourself to yourself. The creative process is the same thing. The figure of woman is, in fact, always present in any creative endeavor, her presence is felt, her virginal or not virginal presence, in every magical or esoteric operation, there is always a woman next to the magician. She is the element that makes the contact between you and your unknown part flow more easily; she incarnates a projection upon your subconscious, which, in turn, is so often represented in art in female form.

I think that creativity itself, that creative expression in all its forms, be it painting or sculpture or film or music, always has this relation to the feminine, obscure part of yourself.

Can we talk, for a moment, of style? How are the fantasies made into images on a screen? What is the first step?

It would be hard for me to talk rationally about the creative process. It’s a matter of constantly maintaining an equilibrium, constantly threatened, between that which you had intended to do in accordance with your imagination and that which you are actually doing.

That’s why I don’t like going to see rushes, like most of my colleagues do, and as I used to do when I made my first films. I don’t want to see what I have shot the day before. They literally have to drag me there when, for example, I have finished a sequence in some big set and they want to pull it down, and the material must be controlled—the cameraman and the production people would like to know if it came out the way I wanted it. Just in case something needs to be reshot. But I often take the responsibility for this: I allow the set to be pulled down without having seen the rushes; I refuse.

Obviously this isn’t folklore or meant to create a legend—“Fellini never goes to see rushes”—but I have realized what happens when one does go: one suddenly is aware of the film one is making, not the one you had wanted to make. Because the one you have been wanting to make is slowly being changed into the one you are making, you are correcting the original idea as you go along. I, on the other hand, like to continue to hold on to the illusion that I am making the film I had had in my head. If I refuse to see what I am really making, I can go on making my ideal film, and the final delusion is reserved for the end, when there is nothing I can do anymore. The film is finished, the crew has dispersed, the sets have been pulled down, and I have to get along with what I have done.

Are there any external disciplines that carry you through the making of a film if you don’t actually wish to see what you are doing?

I think that the psychological type whom we define as a creator or artist maintains an essential, vital component of adolescence, of childishness, and needs an extremely authoritarian customer or boss to pull him along. I, furthermore, am Italian, and we have the tradition of needing a pope, an archduke, an emperor, a king, to give us the order to paint a ceiling for them, to create a fresco in the apse of a church, to write a madrigal on the occasion of a marriage of a princess… and I think that this psychological conditioning, this element of being made to do something, is important to us in our youthful, infantile character as artists. We need external discipline.

Total liberty would be dangerous for those who claim that they want to tell things to others, that they want to recount the world, or for those who pretend to be giving an interpretation of reality. Fantasy offers you its images in a much more suggestive way, much more seductively, much more glazed than the way you will succeed in materializing them. Therefore, it is a very strong temptation to leave the images upon a vague and fluctuating screen. To materialize all those undefined and loose notions is a heavy load of a job. We need something to oblige us to go through with it.

The customer is really necessary to bring off the creative act; to trigger the mediumistic interplay between your inclination—or let’s use this obscene word: your “inspiration”—and the practical act of its realization.

8½ (1963)

If you were to look at your films as persons, what would they be? Sons? Daughters? Fathers? Mothers? Lovers?

No, I don’t think I feel all that close to them. They rather appear to me as strangers, as unknown presences that for a series of mysterious reasons I find myself within elbow-distance of, who pretend to have chosen me and ask me to give them form and character, to make it possible for them to become recognizable to themselves, too. It’s like traveling together in some sort of fluctuating cover, a loose balloon, which I am called upon to fill, to design, to limit, to give a character to.

Once I have done this, as far as I am concerned, our roads diverge completely. He—the film—goes along his road, with the features that I had thought he wanted me to give him, with the identity that it had seemed to me he had wanted me to define, and I go along my road, looking for, or waiting for, another phantom presence, which invisibly elbows me, tickles me, and pushes me to give to it, too, a face, a character, a story.

It all seems to me like a series of relationships with unknown persons, which, once they have been realized, identified, materialized, move away again to the distance, without even saying goodbye. Maybe that’s why I never see my films again. It seems to me that meeting again is not part of the process we have lived together; that his job was to appear and mine to concretize him, that’s all.

Could it be for this reason that the male protagonists of your films always seem vaguely lost?

This idea could be rooted in the past, where on occasion, a bit superficially, the central character has been identified to some extent with its author. Such as in 8½, for example. That seems to me somewhat bold as recognition goes, because I feel that the author can be recognized in all the characters of his film—and not only in the characters but also in the sets, the objects. One can feel a greater sympathy or a greater solidarity with one or another of the characters, and one may choose them to say certain things that one might, in an illusionary way, think are more of oneself than others, but normally that never happens.

It doesn’t happen this way; you can’t just put into the mouth of one of the characters your own way of thinking or your philosophy and then hope that this will be the thing that will come out the most expressive. On the contrary, I find that the things that best express the author are the least conscious ones, the ones that have been the least subject to a process of rationalization and conceptualization. I think an author reveals himself most clearly exactly where he has had no consciousness at all of the thing that he was doing.

In Fred and Ginger, in which the main male role is played by Marcello Mastroianni, the person most often associated with your alter ego, and the main female role by your wife, Guilietta Masina, is there an element of this superficial identification between character and author?

Well, if I reflect and seek the programmatic elements in what I am doing here this time, maybe yes, because through Mastroianni I hope to relate a more or less sincere, a more or less exhibited, a more or less hypocritical discomfort of my generation. He plays an old step-dancing ballerino who for years had not worked in his profession and had done other things, and having retired to the country is suddenly called back by television in order to repeat, together with an old companion of his, a lady friend, a certain dance number, which had once been done by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Quite possibly I am giving, more or less consciously, to Marcello something—gratifying to me)—to express the discomfort and melancholy, more or less pretentious and more or less sincere, of finding himself on the edge of an age at which he has difficulty in remaining in step with the reality that surrounds him.

But these are simple tricks, coldly calculated, and I don’t think that it all amounts mysteriously and without consciousness to an identification with myself that I cannot control.

Ginger and Fred (1986)

It’s been 23 years since you last worked with Giulietta…

Well, yes. It’s true that this little film has stimulating aspects in this sense, even though for some time now I’ve been arriving at the actual point of making a film in a state of mind that is almost antipathetic to it. I resent the film at this point, I make believe that I am forced to do a thing I no longer really want to do, I begin to consider it a frivolous undertaking, a feeling of irritation that accompanies all things one is forced to do. But I must tell you that I am used to having these feelings and that I know they are the signs of the film being ready in me. This antipathy, this hate, indicates to me that I must begin.

This symptom, for the past 20 years, has become ever more precise, and one might be justified in asking me, “Well, why are you making it then?” I make it because for better or worse I have arrived at the point of such unease that I must make it in order to free myself of this unease. I escape; I make the film as if I were in flight from something, to get rid of it, to get it off my back. Like getting rid of an illness.

I don’t want to exaggerate, now, the pathological aspects of a creative act, but deep down, that’s what it is. This unknown one, the one I was talking about before, who is neither son nor father but a presence suddenly all too close to me, urging me to give him life, is a kind of infection. It’s the invasion into my life of something I could easily have done without. But then that’s my life and my destiny and, after all, my vocation.

Recently these unknown presences have become more and more disturbing because they force me into a relationship that is ever more disquieting and upsetting. I don’t know how it all started, this feeling of unease and bother and repulsion. Probably because in the last decades my films, before getting a chance to start, have had all the time in the world to allow me to lose my enthusiasm. This endless waiting in a parking zone while the details are being worked out is enough to dissolve my initial excitement. While the producers are making their deals, trying to establish an economic-financial platform on the basis of their greediness and gluttony, I hang there like a diver on a high board, constantly poised for the jump, hands pointed in front of me, constantly held back because they still have to build the pool, put water in it, and accumulate the spectators. In the end you are no longer doing a high jump but are throwing yourself off the board to get it over with.

Then something else happens. As soon as I get to the studio, despite all this neuroticism, I begin to feel again the fascination of the stage with all its attractions. I see the crew all ready, the sets all built, and when the lights are being switched on, I submit to the romance of it all. I’m back being a marionette artist, the puppeteer, and it all suddenly becomes pleasant again. I recognize that this is my life, I recognize myself in it. All that unease passes.

Do you feel that the public is ever less sensitive to art, that the quality of life is diminishing, and if you feel this, do you think this is caused at all by television? Does this film that you are making about television represent this attitude?

Yes. But this is not a question; this is what I would have said. The answer is included in the question. But one cannot take seriously that the public no longer loves the cinema and wants a type of spectacle of a kaleidoscopic, sensational, and senseless nature. If you accepted this, you’d have to resign yourself and change your profession. Go back to being a journalist or open another shop to sell caricatures of passersby, like my “Funny-Face-Shop” in the years after the war. I can’t think about this.

I must be aware of what is happening around me. It is useless to hark back to generational nostalgia, to make Amarcord with laments in them, or to make moralistic works, because obviously the generation after one’s own always disperses and disbands our values and goes pell-mell after its own. Punctually, every generation seems to have this apocalypse happen to it. It’s been happening for millions of years and so finally it’s happening to us. But although it’s a known fact, when it happens to us it’s a bit more disquieting because suddenly there is a horizon in front of us upon which we can recognize no landing ground.

You are not saying, surely, that you plan to adapt to television’s demands?

What I am trying to say is only that it is almost impossible to account for the wishes of a public born of a television style, influenced by a constant bombardment of images in which man believes he recognizes himself. For 24 hours a day we are exposed to something we think is a mirror, and narcissistically we stay there, watching what “we” are doing the world over. We think that we see what we ourselves are doing, the stories we are living, while in reality we see all that in a form which robs things of their reality.

It’s a form caught halfway between shots of reality and things written and performed for television, between fantasy and publicity. This has created, I think, a highly impatient kind of spectator, neurotic and hypnotized, of whom we, who create cinema, cannot claim to understand the desires he may harbor. Actually I think he doesn’t harbor any desires. He just wants to see images that move with a soundtrack spewing forth clangors of various kinds (which he thinks is music)…

While I do not want to risk appearing to have opinions that seem dated, I must state things as they really are, and see that television is a method, a form between us and reality, with which of necessity we must count and with which we must confront ourselves. One should make the effort to conquer and to possess this form, instead of allowing this form to possess us. Television has become a natural force—like gravity, like lunar influences, like sunspots, like earthquakes—and thus our struggle is with this form, which we have invented but which we no longer control. It is a force that continues to exist despite us or all our intentions.

A maker of cinema cannot afford to take into account a spectator who has undergone such a mutation, who has become alienated and diverse. But of course he cannot, either, disregard him. I personally derive great stimulation from this problem; I am not one of those who say “the cinema is dead”; “television killed it”; “the remote control unit has destroyed the viewer’s ability to follow a story line”; “there is no more space for characterization,” and so on. But of course these things are true. We’ve got to live in the world the way it is.

Or, at least, the way it appears to be. And I don’t think television is something entirely negative. I think it has helped destroy a series of structures, schemes, panoramas, and ways of thinking that have kept human beings in a kind of prison composed of ways of seeing existence. Television is a kind of laser ray that is destroying all that.

I don’t think this is the end; I think out of all this destruction may grow a new relationship to reality. And thus a new way of being man. I find it exciting to be a witness to this development, and to try and find a way, myself, of how to continue to tell things within our tradition but in the style and within the requirements of this new way of life.

So Fred and Ginger will not be a polemic against television, after all?

There is an element of that in it, as well, in a funny way, as a joke. But primarily the film is an attempt to understand how one could try to understand this form. And how to dominate it, if possible. I cannot tell who will come out of it victorious: the destroying ray or the human being.

I am fairly optimistic, though. I feel that everything has a meaning, and I don’t believe that things can be totally senseless. I think that in the end significance will win out over lack of significance.

The characters in your films were always exceptional, but television makes us all alike. Can you adjust to that?

Television is a big container. The real difficulty I am having with this film, which modesty pretends to suggest—within the limits of my ability—a small, delicate reflection or rethinking over the television bombardment, over this total inundation of millions and millions of homes all over the world, is this: using the same means television employs, using its own language, using the infinite variety of its imagery, to try and make those who look at this landscape, at this same bombardment, understand that it is possible to make a small reflection—to put themselves, for a moment, on the sidelines, away from the frontal exposure, so that they may see, from this position, what is actually happening. That is the problem: to say all this but to do it by using the same material the viewer is subjected to 24 hours every day. I hope I can do it. If not, we’ll meet over my next film…

Really, then, what you are trying to do is give back to television that which could perhaps be called its Renaissance aspect?

Yes, and that’s a nice conclusion, which I am grateful to you for.