Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Mike Nichols was certified a genius at age 12 (as Michael Igor Peschowsky, b. 1931, a wartime refugee from Berlin) and became a show-business legend as early as his triumphant comedic teaming with Elaine May—which is to say, dating from the mid-Fifties (University of Chicago days) and culminating in 1960's Broadway showcase An Evening With Mike Nichols and Elaine May. He started directing for the stage in 1963, with Neil Simon's Barefoot in the Park, the first of many successes. His conquest of the screen began three years later with one of the high-profile Events of the decade, the film of Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (66) starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. That brought him an Academy Award nomination; the Best Director Oscar itself followed for his second film, The Graduate (67)—all the more signal an honor, given that the movie itself lost Best Picture to a badly dated social-consciousness melodrama.

The Graduate is dated, too, but in a way that only redounds to its glory. One of the biggest hits of the late Sixties—and one of the first films, along with its fellow zeitgeist phenomenon Bonnie and Clyde, to compel multiple revisits by what soon became “the Film Generation”—The Graduate is a time capsule movie. Not just for preserving memorabilia from another era, or allowing graybeard Boomers to bathe in the parsley-sage-rosemary-and-thyme redolence of the Simon and Garfunkel soundtrack and the cultural mindset it spoke to, helped engender. No, more than that, The Graduate plugs us back into a moment in the consciousness of the American movie audience.

The Graduate

Students of film history and film style can cite milestones till the cows come home, but for the millions who never gave a thought to matters like camera placement or shot duration or the focal length of lenses, no other film in going-on-seven-decades had so decisively or deliciously made so many people notice the kinds of selection and design that can go into making the movie experience. As just one among a myriad of jewels, recall the deep setup, with its judiciously shallow field of focus, from the Robinson family bar to the front hall and curve of stair, and the minutes-long suspension while in the crisp foreground Mr. Robinson (Murray Hamilton) joshes with the terrified Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), and we wait for Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), whom Ben has just barely managed not to be seduced by, to reappear, a blurred but hieratically vivid silhouette, on the staircase. Or the post-seduction “Hello Darkness My Old Friend” sequence, with Ben in and out of the Braddock family swimming pool, in and out of the adulterous bed at the Taft Hotel, which cutting and camera movement suggest is right there in the Braddock home, just on the other side of the door from Mom (Elizabeth Wilson) and Dad (William Daniels) in the kitchen, knowing and not-knowing what's going on. The shifts in time, space, real/unreal, fantasy/paranoia/distraction: people could see it, it was cool. They knew it had something to do with the way their own lives, their own suddenly-so-modern world, had come to look and feel. And they knew that they were being made to know and feel this by the way the film had been conceived and breathtakingly realized.

Nichols would never again make such a quintessential “young man's film,” flaunting his discovery and mastery of a new medium. But over the years his films have remained true to the urge toward precise definition—distillation—of character and lifestyle so ringingly keynoted by the great Nichols and May cabaret sketches. Indeed, the majority of his work constitutes a kind of bildungsroman of his adopted hometown, New York, as authoritative as the filmography of Woody Allen. So many Nichols people are grappling with their own glibness, variously concerned with or doing their best to ignore the question: is the act I'm putting on a really good one, and if I somehow ever stopped, would I find out that the act is all I was? (Nichols and May's favorite, most dangerous improv was named “Pirandello.”) Yet he has rarely been locked in by shtick. His style has continued to evolve, from the compulsive (and tactically essential) field-marshaling of detail and spectacle in Catch-22 (70), through the Feiffer-like abstraction of Carnal Knowledge (71), to the plain-spoken power of Silkwood (83)—the heartland enigma of a working girl (Meryl Streep in the first of several superb collaborations) who either willed herself a martyr, lived out the compulsiveness of a born victim, or was unaccountably touched by amazing grace.

Working Girl

Silkwood was not only a leap into the equivalent of a foreign country for urbanite Nichols but a major turning point. Abandoning his wellnigh absolute adherence to the long take and a European (or arthouse) tolerance for duration, he became less an homme du cinéma, more a guy who made movies. As such, he has sometimes been grievously underrated: not for the swell comedy-romance Working Girl (88), which won a passle of Oscar nominations (including Nichols's own fourth), but definitely for the inside-Hollywood trompe-l'oeil of Postcards from the Edge (90), with Meryl Streep and Shirley MacLaine as daughter and mother; Wolf (94), a witty, elegant horror-movie gloss on the rapacious careerism of the Smart Set; and Primary Colors (98), a scrupulously ambivalent portrait of Clintonian politics so dead-on it was short-circuited at the box office by the contemporaneous headlines that confirmed its accuracy.

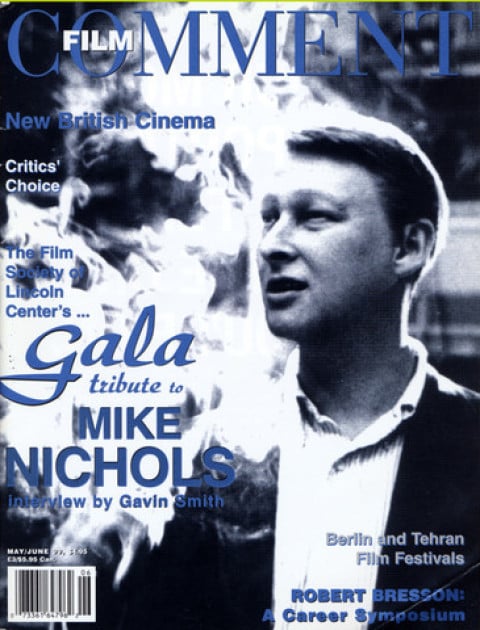

And so for its 26th annual Gala tribute, the Film Society of Lincoln Center honors Mike Nichols, Monday, May 3, 1999, in Avery Fisher Hall. We can only hope to hear him greeted by frequent screenwriter, actor, and sometime Taft Hotel deskclerk Buck Henry: “Are you here for an affair, sir?”