A Matter of Skin. . .

A long time ago, before the country got priest-ridden, a traveler passing through an Irish crossroads might have encountered a standing stone image, the ancient equivalent of a traffic light. Crouched, grotesque, this exaggeratedly female figure was called a sheila-na-gig. Her face set in rictus frown or ferocious hilarity, she was a Celtic earth mother who held her nether mouth wide open, as come-on and caveat, green light and stop sign. Patting her labia—curtains on an eternal stage—she kept humankind in everyday touch with their source and ending, a primal dark both grave and gravid, magnetizing and monstrous.

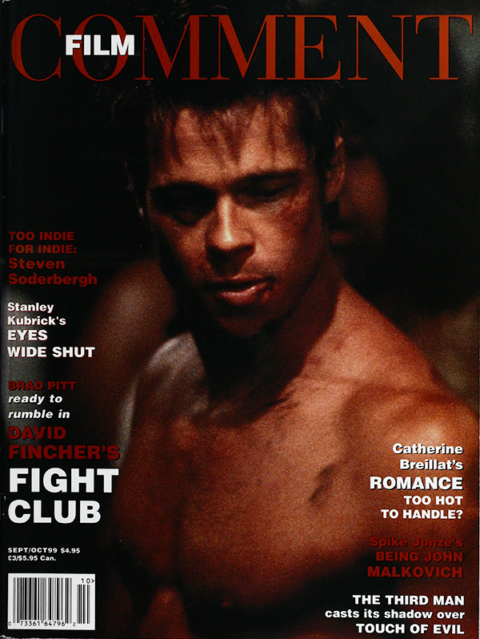

Dominated by male, mostly illiterate directors, adolescent demographics, and a peculiarly American aversion to seeing sex as meta-physical, our homegrown movies rarely take us anywhere near that dangerous dark. (Pace Kathryn Bigelow, who’s got the mojo but not the screentime.) To find mainstream films nowadays that convey the primal, uncensored energy of specifically female libido—expressed as both sex and art—one must either turn to Jane Campion or cherchez les femmes françaises: most especially Catherine Breillat, a dauntingly courageous connoisseur of carnality on page and screen.

Breillat was a wild child who matured early, a provincial isolato steeped in the likes of Sade and Lautréamont. Since 1968, she’s obsessively pursued la vie sexuelle through a half-dozen novels and six uncompromising feature films that she both wrote and directed: Une vrai jeune fille (76), Tapage Nocturne (79), 36 fillette (87), Sale comme un ange (91), Parfait amour! (96), and Romance (98) . Along the way, Breillat’s been actress (Last Tango in Paris, Dracula et fils) and screenwriter, most notably of Maurice Pialat’s Police.

Her first novel, the semiautobiographical L’Homme facile in 1968, was banned as outrageously “dirty,” and her debut film Une vrai jeune fille—about a fantasizing teenager solipsistically (and graphically) exploring the possibilities of her ripening flesh—roused a similar brouhaha. (Screened as part of last year’s Breillat tribute at Rotterdam, the film is unavailable here due to contractual difficulties.)

Romance, her latest film, has been hailed as erotic breakthrough and denounced as clinical pornography. One can’t imagine such a singleminded, noncommercial career surviving several decades in Hollywood or even Indieland. In addition to governmental subsidies for filmmakers, France provides at least some hope of a core audience with a taste for writer-director Breillat’s “erotic encephalograms,” the cinematic equivalent of D.H. Lawrence’s “thinking in the blood.”

Catherine Breillat’s vision is definitely not for those turned on by balloon boobs and dumbsticks on automatic; shagging as sexy as planes refueling in mid-air; man on top/full breast but no penile exposure/crescendo of moans and cut! sex scenarios—all the component of the cartoon school of filmmaking that infantalizes (and masculinizes) the American sexual imagination. Nor are Breillat’s films for inquisitors who shrink down every idea and experience, in art s well as life, to fit the strictures of political correctness. Taking sex seriously is nearly a lost art—and the transcendent act of taking sex seriously is what Breillat’s art is all about.

You might say that Breillat makes the same movie over and over, variations on what she calls a “sacred” theme. Whether her heroines are Lolitas, twentysomethings, or mature mothers, they incarnate mystery; their sexual rites of passage are as mesmerizing and potent as Le Passion de Jeanne d’Arc by Dreyer. From Falconetti to Anna Karina (witnessing Falconetti in My Life to Live) to Breillat’s Delphine Zentout (36 fillette), Lio (Sale comme un ange), or Caroline Ducey (Romance), the directorial eye sink into, consumes the unguarded, deliquescent faces of women lost in spiritual/physical orgasm. Dreyer and Godard can’t get close enough to wholly possess their oval portraits; they crowd in to fuck those opaque, radiant visages to death, waiting for them to break water and deliver god’s own truth. It’s an aesthetic ravishment practiced by the likes of Pabst, Hitchcock, Buñuel, and Fassbinder.

Breillat’s creative gaze participates in, even contributes to her heroine’s coming; it never withdraws from the actress’s eloquent face and flesh, registering without judgment every nuance as she is swept by tides of shame, letting-go, ecstasy, and renewed self-containment. Often, enraptured by a lover’s slow hand, she will cover her face with her fingers or hair, as though ritually veiling the soul’s nakedness during la petite mort. If cinema is a holy whore, Breillat and her vestals ultimately embrace the mystery together. Sin bravely, urges their creator; show me where I have been, how far I might go, the crossroads of eros and thanatos.

No matter how often and ecstatically Breillat’s saints burn at the stake, they return to themselves, intact, fertile with new desire. Attractive and complex as the men in these films may be, they remain stations in a woman’s pilgrimage. They are kin to succubus-ridden Kichi-san in Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses, Breillat’s cinematic touchstone, though in the French director’s fairy tales, aging frogs and handsome princes fight fiercely as her dark ladies draw them deeper into a dance to die for.

36 fillette (Catherine Breillat, 1988)

36 fillete is a bra size, and Delphine Zentout’s ripe breasts, bursting out of a tight black corset, seem to have a life of their own in Breillat’s third film, adapted from her novel. Alternately comic and erotic, they precede the rest of her body, still chubby with baby-fat, expressing with ruthless succinctness a sexual identity for which this 14-year-old is still schooling. Lili takes up with an “old Romeo,” a not unattractive playboy (Etienne Clicot) whose bald spot shows though his stylishly trimmed blond hair. Hanging out with callow kids and affecting a predatory cynicism, this sad sack is as bruised and conflicted on his side of the existential/sexual abyss as young Lili is on hers.

All white skin, unkempt black hair, old eyes, and hungry mouth, Zentout’s a vampire child (and a dead ringer for young Breillat) savoring her first taste of power. She stays one-up in the psychosexual seesaw by sucking her suitor off every time he threatens to get inside her. Though Maurice never succeeds in screwing her, the relationship this odd couple shares is far more intimate and emotionally eye-to-eye than the brief fuck with the awkward teen whom she finally chooses to terminate her physical virginity.

From the vantage point of having maxed out his sexual— or any—faith, it’s ambiguous whether Maurice’s immediate connection with this child-woman represents another notch on his gun, the final nail in his coffin, or a new lease on life. Also complexly motivated is Lili’s backing-and-filling when it comes to sleeping with Maurice: she’s a kid who can’t make up her mind, but there’s something wise beyond her years about her refusal—no matter how aroused—to let go, to surrender her selfhood, to become another receptacle for Maurice’s despair. She chooses control and freedom over the risky lure of amour fou, sex that has something to do with death. (Ricky Nelson’s twanging teen plaint “I’ll Walk Alone” backs two decisive moments in Lili’s sexual education; Breillat demonstrates a sharp ear for music in her films, both allusive and aphrodisiac.)

At the heart of almost all of Breillat’s films beats a set-piece, a lengthy seduction sequence that anatomizes carnal communion. (Think of the rhythms of Ma nuit chez Maud played out in the flesh.) In 36 fillette it’s the remarkable evening Lili spends in Maurice’s hotel. Slow-dancing at the Opium Bar, he’s caressed her into a state of drugged, almost swollen acquiescence, but she literally freezes at the threshold, a contrary vamp. Breillat chronicles the night (really early morning) in what seems a long take, punctuated by nearly imperceptible jump-cuts.

Duration on this gold-lit stage feels like deepening erotic trance, fed by currents of heavy silence, separateness, conversational ripostes, then a long, complex sexual tango, with the camera close enough for us to register odor and heat. Reluctant Lili standing, caressed and drawn down to the couch, where Maurice fingers her closer to coitus; Lili, with her hand covering her face, retreating, crawling head down to a further corner of the couch, Maurice’s gently insistent hand pursuing, pleasuring; Lili, suddenly turning ugly, crying rape, thrown down to the floor and fingerfucked nearly to climax; Lili once more resisting, Maurice angrily waving his wet fingers in her face: “Up here you may not want to; down there, you’re dripping with desire!”; Lili reaching down to get him off, then hurting Maurice so badly he almost throttles her; in extremis, Lili almost at postcoital ease, laying down her arms behind her head, her dark gaze bisected by a curving strand of hair. The nearly unbearable intimacy of this protracted carnal corrida climaxes in an homage—with reversed genders—to the asphyxiation in the penultimate moments of In the Realm of the Senses.

Like the Oshima film and Bertolucci’s Last Tango, Breillat’s passion plays unfold in emotional belljars almost entirely insulated from the concerns of the mundane world. In the hermetic atmosphere of these movies, both lovers and those of us marking time in the dark lose sight of any horizon but that of the flesh. So intense are their immolating embraces, it’s sometimes hard to remember whether these men and women have names or public faces.

Parfait amour! (Catherine Breillat, 1996)

In Paifait amour! (Perfect Love!, Breillat’s fifth feature), Frédérique might be Lili, three decades along, seasoned by motherhood and sexual experience. Remixing the dynamics of that earlier version of Lolita, Breillat matches an older woman who’d like to regress from her own carnal authority with an “orphan” boy long gone from virginity. She locks them in a power struggle so incestuous it must go further than the symbolic death that climaxes 36 fillette‘s coitus interruptus.

Breillat’s great gift for casting iconographically is particularly evident in Parfait amour!. Playing the young layabout Christophe, Francis Renand possesses the sharp features of an ancient child; his face cuts through framespace like a knife, hardening from the sweet tenderness of a 20-year-old deeply, romantically in love into a veteran cocksman’s self-defending scorn. Ophthalmologist, twice-divorced, mother of two, Frédérique is perfectly embodied in Isabelle Renauld. She conjures Jeanne Moreau’s mysterious smile and infinite allure as Jules and Jim‘s goddess. The strong , voluptuous curves of her cheeks, her fathomless eyes and luxuriant mane project an erotic/maternal mask that remains opaque even as it absorbs her lover’s/our gaze. Her expressions elide from the scoured shine of a girl’s postcoital satiety to the flat glare of a castrating harpy.

Appropriately, ironically, Christophe and Frédérique come together at a wedding party. Instant soulmates, they commune in a shimmering nighttime garden magical enough for a Rogers-Astaire danse d’amour. Excepting Romance, Paifait amour! is Breillat’s most stylistically formal (and beautiful) film . During that prelapsarian garden-talk and through a series of ever-more-denuding confessions (over dinners, in bed, at bars, on a blued-out Dunkirk beach), her camera is never still. It drifts, almost imperceptibly—like a slo-mo pendulum—from one side of the frame to the other, from speaker to listener, and back again. That insinuating movement unsettles these scenes, which devolve from nourishing embraces into armed combat between cannibals. About one-third of the way through, the film itself reverses direction on the narrative fulcrum of the lovers’ exquisitely Romantic journey into the country.

When Christophe takes his “one great love” to a tacky rural hotel, it’s wedding ceremony and honeymoon—and after his boyishly tender lovemaking, Frédérique tearfully regrets how deeply she’s plumbed the dark side of sex, her lost innocence: “I’ve gone too far with men . . . .” In their next, post-honeymoon bedroom conversation, an armored Christophe will recast her as devouring Kali: “You destroy all your men . . . you’re a praying mantis . . . you won’t break me.” This “sudden” reversal turns on the poetic mystery and logic of the silent-movie passage that bridges the two beddings.

The morning after Frédérique’s tearful “defloration,” Breillat’s camera frames, from the back, the couple in a convertible, their hair whipping wildly in the wind. The shot holds a long time as they drive a hazily white mountain road—the movement disorienting, disquieting, like the fluid unreality of a Hitchcock back-projection. Then, a high shot: the car parks on a promontory overlooking a vista of mist-green valleys spreading like the open thighs of women. A very long shot follows, with imperceptible camera drift sideways, of a great thrusting crag, a zone of dungreen at the bottom of the frame, with tattered veils of white, then sun-flared, mist moving leftwards over the black mountain-face. The eerie silence that shrouds this extraordinarily fateful sequence is pierced only by strings and piano accompanied by a woman’s unbearably sweet, melancholy voice. By means of music, silence, and landscapes both symbolic and solid, Breillat has deftly drawn us into the heart of Parfait amour!‘s darkness: liebestod pure and simple.

Monstrous mothers who castrate their sons tum up in memory only in Sale comme un ange and in the Breillat-scripted Police; Parfait amour! is unique in showing us the honor in the flesh. By means of monthly suicide attempts, Christophe’s mom rubs her son’s nose in bone-deep disgust for herself, a long-gone husband’s omnivorous sexual appetite, and the very children she has spawned out of what she calls rape. She’s like a cancer on his manhood that metastasizes into full-blown fear of and contempt for Frédérique. Entangled in an immutable embrace, Christophe escalates his crude attempts to sever his umbilical connection to mother/lover, branding her ripe female sexuality “a hunk of stinking meat”; while Frédérique decomposes into devouring ball-breaker, assaulting her “faggot”‘s penis size and potency.

In a long, peregrinating duel on a winter beach, Breillat choreographs, with barely a cut, the rhythms of primal male-female alienation and addiction (Christophe rightly calls it “a struggle of giants”). In this cinematic tour de force, the couple circle each other like gladiators, each ripping his/her opponent to shreds, abysses of sexual loathing opening between them; commenting on the warfare as they wage it; gravitating to touch one another in loving time-outs; then escalating to another level of carnage. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Parfait amour! opens with a clinical police enactment of a brutal crime of passion, featuring a colorless young man awkwardly, metronomically wielding plastic-wrapped broom handle and knife in the middle of a kitchen; and climaxes with the crime of passion itself, the horrifically explosive conclusion of the brutal thrust and-parry on the beach. The perfect lovers have been reduced to pure oppositions, anima/animus: unmanned Christophe gets back inside his mocking Medusa mother the only ways he can, “disappearing” her forever beneath the frame. Then, emotionally dispossessed, the “orphan” deflates into ordinariness, into a final darkness filled with the sweetly melancholy music that accompanied that earlier, shadowed “honeymoon” in the country.

Sale comme un ange (Catherine Breillat, 1991)

Falling between 36 fillette and Parfait amour!, Sale comme un ange (Dirty as an Angel) makes a provocative marriage between policier and a grim fairy tale about a lonely Beast’s lust for seemingly innocent Beauty, who shapeshifts into la belle dame sans merci. Full of images that resonate with the dialectics of mortality, Sale is one of Breillat’s most visually tactile works. Our senses are assailed by juxtapositions: the flow of sand through a child’s hands as he shapes a sandbox grave for his missing father, and the heft and hardness of the gun his dad’s comforting friend lets him shoot. A pink bathrobe, its texture rich as some exotic pelt, pressed against heavy black leather. The afterimage of a young woman’s taut, naked body curved provocatively on a bed, superimposed (in the mind’s eye) on a man’s pajama’d corpse sprawled on a dirty mattress, gray flesh swollen with decay.

Sale‘s lovers are physically so paradigmatic they suggest allegorical members of separate species. The sad, much-used flesh of Claude Brasseur’s face and body looks to have collapsed into thick lines and folds of coarse disillusionment; and his obligatory black leather jacket must be seen as a kind of macho carapace. At first look, the fine-boned Lio projects the guileless diffidence of a ponytailed child. But her great cape of black hair, hungrily sensual mouth, the heavy brows and oddly alien gaze betray her true face: this dark lady is as “dirty” an angel as any of Buñuel’s double-natured objects of desire. Among Breillat’s expressions of primal femaleness, Sale‘s Barbara is perhaps the most disturbingly hieratic, combining a passive gift for orgasmic abandon with active resistance to self-shattering intimacy.

Partnered with Didier, a young Don Juan (Nils Tavernier) for whom sex is little more than a “great pick-me-up,” aging flic Deblache (Claude Brasseur) seems equally steeped in carnal impiety (“Time I tore off another piece,” he announces, rolling over on his bed-partner). But this much-fallen cop’s a pushover for Barbara, Didier’s new wife: fastidious, self-possessed, a “princess”; in short, an unfamiliar breed of woman. Initially, she’s just another chance to follow in handsome Didier’s sexual wake, as the older man is wont to do. But Barbara’s allure cuts deeper. She recalls “forbidden” flesh from which he has been exiled since birth, a mother who rejected her child’s ugliness and made him old before his time, In arousing his ice princess to helpless passion, the bullish Deblache goes home, potent mate and beloved son.

It’s a primordial drama, but the balance of power shifts radically during the three acts and shattering epilogue of Deblache’s relations with Barbara. After a steamy evening of up-close and graphic lovemaking with his utterly pliant princess (variously clothed in pink and blood-red), Deblache is so deep in her sexual thrall he vows that “I’ll give up living to go on wanting it . . . It’s a matter of skin . . .” Following their next-day tryst, restive Barbara slides out from under her lover’s dead weight to curl up in an easychair. Missing her, afraid she’s deserted him, Deblache comes to perch on the arm of the chair, then slides down to sit on the floor. She leans over to play with his graying hair; then, after confiding his mother’s coldness, Deblache turns into his sympathetic confessor’s embrace. Now participant in a sexualized pietà, Barbara’s altar boy measures her sway over him: “I go all soft . . . everything I hate.”

The lovers’ third act follows hard upon Deblache’s discovery of a gangster pal, murdered, his decomposing body an ugly exemplum of mutable flesh. While Deblache recounts the history of this old friendship, trying to convey the peculiarly male quality of their bonding, Barbara has eyes only for her own mirrored image. Brushing her hair, then drawing its blackness across half her face like an Arab woman’s veil, she lashes out in a castrating assertion of female autonomy—reserving her pity for the dead man’s wife, accusing Deblache of screwing her rather than helping his pal. Finally, delivering the coup de grâce, she rejects the hold he has over her flesh: “I hate coming! I hate myself when I come!”

Sale‘s epilogue culminates in a freeze-frame both celebratory and utterly chilling. Unconsciously or actively inspired by his sweet succubus, Deblache has smoothed the way for Barbara to become a pregnant widow. Now, at Didier’s funeral, he tracks her zig-zagging retreat through a landscape telescopically chockablock with white gravestones. At his “Mrs. Theron,” she turns smiling. Backhanding her across the face, Deblache spits out, “Bitch!” Breillat freezes Barbara as she turns back from the blow’s momentum, her hair a curtain in motion, her smile . . . intact. Sheila-na-gig inca rnate, Deblache’s grinning mother—wholly at home in her gravid flesh—flaunts her control over life and death.

In its chronicling of a woman’s perilous quest for self-knowledge through sexual experience, Breillat has suggested that Romance can be seen as a kind of fantasy remake of the more realistic Tapage nocturne (Night Noises). That earlier film (again, adapted from one of her novels) features a filmmaker backed financially by a husband who does not dominate her bed. Abroad in bars, stairwells, and attic rooms, Solange searches for metaphysical inspiration, sex so imaginative and strong, it might conjure the feeling of first-time. In some sense, Tapage nocturne and Romance both conflate sexual and creative passion. For Breillat, the revelatory gifts of transcendent fucking—flowing from that nether, vertical eye—are inextricable from a filmmaker’s prolific, clarifying vision.

Romance (Catherine Breillat, 1999)

In Romance, Caroline Ducey’s resemblance to Sale‘s Lio is remarkable; but in Ducey, Lio’s earthy exoticism rarefies into a more lunar, fragile beauty. Dming her S&M “appearances,” Ducey metamorphoses into something like pure “thingness,” but she’s too transparent to achieve the force of Lio’s not-quite-human impenetrability. And she talks far too much. Part of the hypnotic charge of Breillat’s libidinous images comes from the fraught silences in which they play out. It’s like being in church, witnessing sacramental rites. In Romance, Ducey’s Malie maunders on in voiceover, sometimes fatuously, sometimes poetically generalizing her specific sexual adventures into philosophical axioms. These cavils aside, Romance in its slow, intense efflorescence is far more unnerving as a carnal traumnovelle than the emptily portentous Eyes Wide Shut. In her most metacinematic effort, Breillat projects wet dreams that show the fecund sexual imagination at play, silly, orgasmic, murderous, Romance explores the shame and pleasure of getting naked for the camera eye, and the ambiguous nature of our (the viewers’) eyeballing of filmed objects of desire.

Romance opens on a fashion model’s face (and closes triumphantly on a mother’s). Paul’s eyes are closed, his lips bloodred, and white makeup dusts his cheeks; it’s a Kabuki mask of stylized, almost effeminate good looks. His girlfriend (Caroline Ducey), a nonparticipant all in white, watches from the sidelines while he (Sagamore Stévenin) plays arrogant matador to a “submissive” distaff costar in a commercial. Afterwards, in a café, Marie weeps as Paul reiterates his lack of interest in fucking her —or anyone—after the first two or three gos. In the antiseptic order of their white bedroom, this centerstage mannequin is cruel provocation: desirable flesh supine, immobile, virginal in white T-shirt, shorts, and sheets—refusing to touch Marie, occasionally giving her special dispensation to go down on him. When they go nightclubbing, Paul likes to have Marie watch as he dances with other women, challenging and teasing them with his sexuality. “If you say it’s chore time, I’ll do it,” he tells sex-starved Marie, “to make a baby.”

Consistently working a very subversive vein of humor, Romance turns the gender tables on us: in movies, Paul’s lack of libido except in the service of public performances and dutiful procreation is most often attributed to narcissistic, repressed women. Such women drive their men out into the world in search of satisfaction; in Romance, it’s Marie who nightly exits Paul’s cold, arrested “stage” to tryout other men, livelier mise-en-scène. Along the way, as sexual auteur, she develops her own scripts, set design, and choice of costars.

Marie’s first foray into an alternative film de charme (porn movie) features Rocco Siffredi, veteran of innumerable Italian skin flicks. Driving through quintessentially French night streets—rainslicked, narrow, neon-lit—she stops in at a bar, instantly catching the eye of a handsome hunk. Her narration begins to overheat in romance-novel style: “His girlfriend died in a car accident . . . he hasn’t had sex in six months . . . he’ll have to realize it’s adultery.” Later, in a room suffused with golden lamplight, their naked, beautiful bodies become the stuff of softcore art. Ironic, of course, to cast Siffredi as tender lover, Paul’s opposite: his erect cock rises between them, eternally at Marie’s service; the perfect audience, he’s silent, attentive, as she blathers on even while they’re fucking.

For her next closet drama, schoolteacher Marie auditions as the willing plaything of her homely, utterly unprepossessing principal (François Berléand), a connoisseur of the pleasures of S&M. Amid his apartment’s Oriental, scarlet-splashed ambience, on a little stage, in front of a mirror, against a window, this delicate woman in a little white dress, her lush black hair tied back, becomes a kind of debauched China doll, cynosure of all eyes. (Think of Belle du jour‘s Séverine.) Despite Robert’s litany of unlikely conquests—”I talk to women . . . they are in the palm of my hand”—and the initial drollness of her director’s deadpan manipulations, their first act together evolves into one of Breillat’s most hypnotic, racking sexual passages.

Cornering the retreating Marie, Robert fingers her into ecstasy. After Breillat shows us Malie’s wet sexe in closeup, her other director displays her passive flesh in front of a minor, dress up, panties around her knees. Gagging her, he ties her arms up above her head and continues to painfully rope her quiescent body, crotch bared, in a design so elaborate it almost prompts uneasy laughter. Hanging helplessly, utterly exposed, Marie eventually breaks: “It’s a form of dying,” she wails; we believe her, because Breillat has drawn us into this long ritual so completely we are implicated in Marie’s violation, the complete reduction of actress to shamed, beautiful object.

For her second “immorality” play, Malie’s costumed in scarlet dress and black bra; black hair curtains half her face, white rope necklaces her throat and torso, and she’s gagged with black silk. Posing patiently on the edge of Robert’s little stage, she solidifies into stylized chinoiserie, sculpted into an impossible, ideal form by her various bindings. Meanwhile, Robert rummages noisily through his metal toys, looking for precisely the right prop to complete his exquisite tableau vivant. This perversely funny moment takes nothing away from Marie’s patently orgasmic response to her metteur-en-scène; even as the joke extends into a post-bondage runner during which her dominator is unable to command the attention of their waiter.

On the stairs just outside Paul’s apartment, Marie makes a third stop in her tour of sex acts. There, for a pittance, she allows a brutal stranger to bury his head between her legs; unsatisfied, he then slams her over on her stomach to rape her anally. (“Maybe I just want to meet Jack the Ripper,” she considers afterwards, prompting us to recall the end of Louise Brooks’s Lulu, the eternally unsullied sexual adventurer of Pandora’s Box.) This short, humiliating encounter, opposite in every way to the golden ceremony that began her journey, marks the conclusion of Marie’s sampling of pornographic performance art.

The scenes that comprise Romance‘s giddy denouement grow increasingly surreal, particularly one that features something like a Terry Gilliam version of a phenakistoscope out of which at intervals protrude the naked, splayed lower bodies of women, leered over by masturbating men. Semen smears what turns out to be Marie’s tummy; on the other side of the circular peepshow, Paul, proud-father-to-be, beams, while her abdomen’s slathered with cream in preparation for amniocentesis. There’s hilarity mixed with horror in that female dichotomy; those oppositions are also generated by the simultaneity with which the infantile Paul disappear·s (via a gas explosion Marie rigs) and the young/old face of his son and namesake pushes out of Marie’s vagina, to peer at us in disconcerting closeup.

Romance‘s epilogue echoes—with more humor—the conclusion of Sale comme un ange: Marie attends Paul’s funeral, babe in arms, the mise-en-scène as melodramatic as horror movie or early Buñuel (say The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz). Marie, onetime “slab of meat,” smiles radiantly into the camera, our eyes—star and director of her own movie at last.

Medieval Christian poets used to compose ardent accounts of steamy wrestling matches between body and soul, salvation the prize. In her brave, passionately intelligent movies, writer-director Catherine Breillat graphically expresses an older tradition: her pagan eye rejects that rupture to remarry skin with spirit in a potent metaphysics of sex. In today’s cinematic climate of carnal benightedness, it’s a consummation devoutly to be wished.

Kathleen Murphy wrote about In Dreams in our March/April issue.