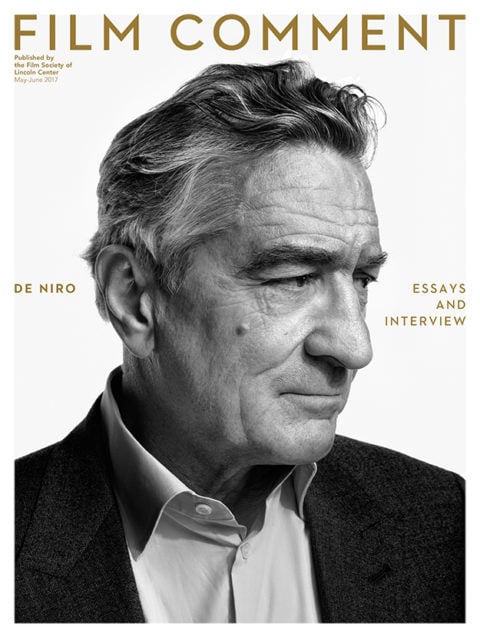

A Man Apart

In Awakenings (1990), Robert De Niro’s Leonard Lowe, a catatonic emerging from the 40-year sleep of encephalitis, looks in the mirror, scrutinizing the face of a self he barely recognizes. “Who am I?” he seems to ask, and we might ask the same of him. A man without experience or memory, a man without a through-line—a description no less eerily apt for the actor himself. De Niro, appearing in films great, good, bad, and terrible for nearly 50 years, receding into the background as often as he grabs the spotlight: he is everywhere and nowhere, impossible to pin down. Or as the British saying has it, Who is he when he’s at home?

Other mirror scenes: in the extraordinary echo chamber of the most famous scene in 1976’s Taxi Driver (“You talkin’ to me?”), we are watching an actor improvising a character (Travis Bickle) improvising a killer in front of a mirror. In the companion scene in Raging Bull (1980), an obese De Niro, sitting before a dressing-room mirror, impersonates Jake LaMotta practicing his impersonation of Marlon Brando playing Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront. The two most famous soliloquies in modern cinema take place in front of mirrors, images that still taunt us with the ever-receding and indecipherable mystery that is Robert De Niro.

We expect filmographies to resemble biographies, evolving with a discernible shape; there are the “departures” from type that inevitably become exceptions that prove the rule. But what is the rule in De Niro’s case? What connects the smoldering or overtly menacing figure of Taxi Driver and the early films to the self-parodying gangster of Analyze This (1999) and CIA agent of Meet the Parents (2000) to the skirt-chasing, obscenity-spewing geezer in last year’s Dirty Grandpa?

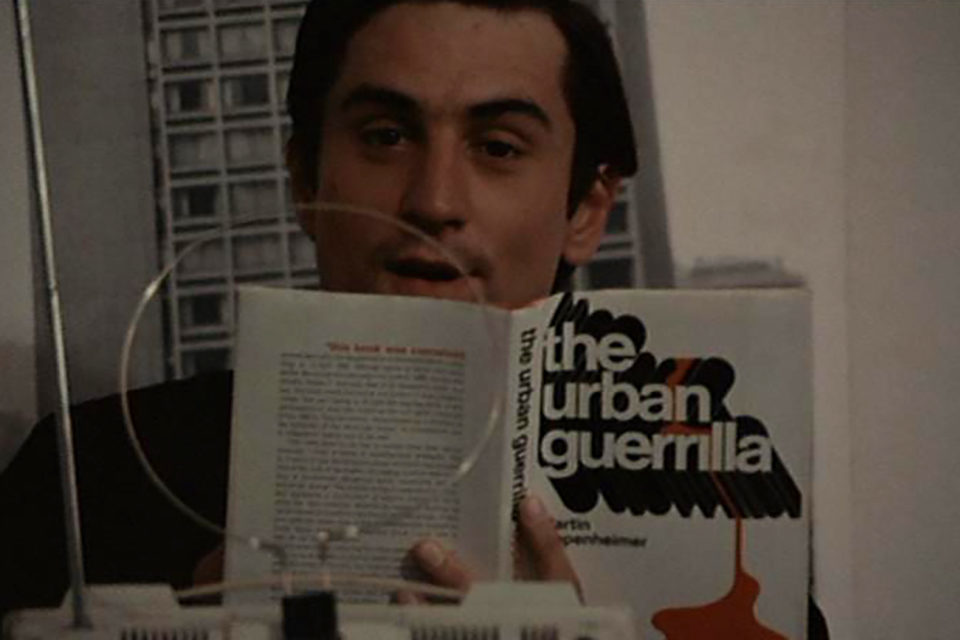

Hi, Mom!

People were trying to get a handle on him from the outset, but maybe we should have listened when, as the opportunistic sometime-actor in Brian De Palma’s Hi, Mom! (1970), he boasts, “I can play anything.” Critics who rhapsodized over his hopped-up punk in Mean Streets (1973) and avenger-kook in Taxi Driver were outspoken in their disappointment when he seemed to disappear into quiet roles like Monroe Stahr in The Last Tycoon (1976) and the priest in True Confessions (1981), as if an exotic, wild animal had been captured and neutralized. But the wild beast (“I’m not an animal,” as he cries in Raging Bull) was no more “who he was” than the buttoned-down executive or solemn cleric.

De Niro’s art has always been the art of disappearance. Whether in costumes—he’s been described as fanatic about wardrobe, spending hours getting it right—or in that ultimate costume of his own ever-mutating body, or working harder and for longer hours than anyone else (Elia Kazan said he was the only one who worked on Sundays), or eating his way around Italy to prepare for latter-day Jake, he was consuming and being consumed by his roles, working from the outside in rather than drawing on some autobiographical reality.

This use of makeup and appurtenances was closer to the English way of acting than to the Method. Yet even early on, as Glenn Kenny reports in his fine De Niro edition of Cahiers du Cinéma’s Anatomy of an Actor book series, he never yearned for the theater. Movies are his magnet and his medium, the camera the mirror that confirms his existence.

To read the rest of this article, purchase the May/June 2017 issue.