A Lifetime in the Moment: Robert Duvall

If any actor could be said to be incapable of a false moment, it’s Robert Duvall. Duvall carries his profound talent lightly, with a master’s relaxed assurance and effortless authority. Look at any Duvall performance and you’ll see that it has no use for glamour, and that the work ethic is paramount. He toiled steadily as a character actor on episodic TV and in movies all through the Sixties, and a supporting role in 1972’s The Godfather was the first payoff. You could call him the anti-Redford (he had supporting roles in two Redford films, The Chase and The Natural), advancing the cause of realism in screen acting with integrity and responsibility and with no regard for the office of stardom. This elevation of acting to new heights of naturalism and simplicity assumes an almost ethical dimension when linked to Duvall’s social-realist insistence on sticking to the truth of real life and experience. In this and many other respects he is close kin to Gene Hackman, with whom he roomed when they were both struggling actors. Curiously, apart from an oblique one-scene encounter in The Conversation, the two never worked together until 1993, in Geronimo: An American Legend—though both had played characters based on New York cop Eddie Egan in the early Seventies: Duvall in Badge 373, Hackman in The French Connection.

Much of Duvall’s work belongs in a cinematic pantheon of American masculinity, where his enduring theme is a familiar one: the temperamentally solitary or difficult man’s uneasy accommodation with domesticity, exemplified by his Navy pilot in The Great Santini. His performances span a continuum stretching from the egoless quietism of his stoic, enduring sawmill caretaker in Tomorrow and his efficent, self-effacing consiglieri in The Godfather to the posturing egomania of his air cavalry Colonel in Apocalypse Now and his verbose criminal dandy in The Lightship. Duvall is adept at country folk and urban types alike, though he has gravitated towards the former in the latter half of his career, at least partly by dint of a lasting association and collaboration with screenwriter-playwright Horton Foote—beginning with To Kill a Mockingbird and The Chase, pivoting on Tomorrow, and continuing through Tender Mercies and Convicts. Though he seems to have retired it, for a time Duvall had one of American cinema’s great improbable laughs—a hoarse, staccato bark, deployed to devastating effect in Apocalypse Now. In its ne plus ultra manifestation, the car scene in The Killer Elite, it finally suggests the hysterical or neurotic underpinnings of hypermasculinity—territory Duvall would definitively map in his legendary performance as Teach in Ulu Grosbard’s Broadway production of David Mamet’s American Buffalo in 1977.

A tremendously compressed interior life also made him an ideal incarnation of the paranoia and alienation of the contemporary-futuristic organization man of THX 1138 and The Conversation. By the same token, two of his greatest performances—his country singer hiding from life but facing hard facts in Tender Mercies (for which he won an Academy Award), and his resentful detective sibling worn down by the attrition of unspoken feelings in True Confessions—are indelibly poignant studies in inarticulate introspection. Latterly he has come to be what one might call an elder statesman, but for his indifference to status: the weary grace of his veteran Texas Ranger in the TV miniseries Lonesome Dove, the humane professionalism of his retirement-age cop in Colors, and the gentle paternalism of his country doctor in Rambling Rose shade into the crumbling ruin of his senile autocratic plantation owner in Convicts and the dazed shadow of a man he presents us with as Billy Bob Thornton’s father in Sling Blade, unreconciled in his dementia. What finally unites all of Duvall’s performances is this: a sense of vigorously exercised will, of deliberate purposeful action, of fixed, absolute presence.

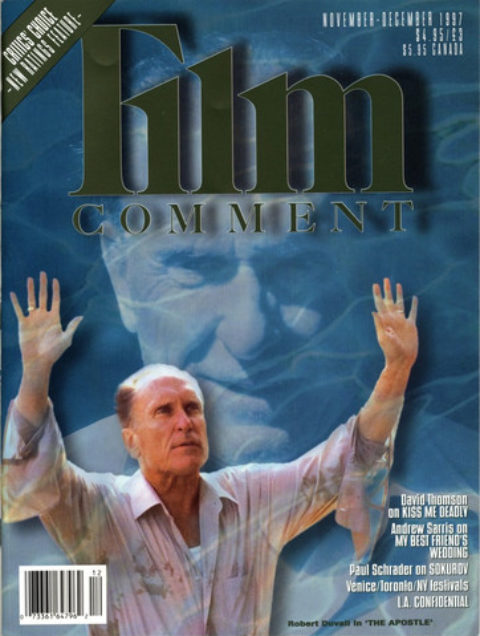

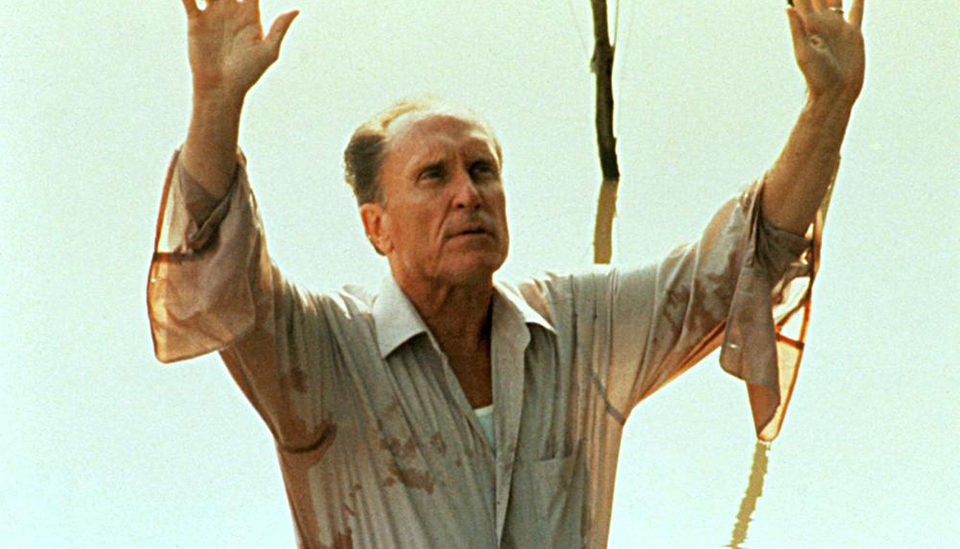

Duvall’s unshakable dedication to and curiosity about the truth of ordinary lives in all their contradictions, to the sublime or exotic that can lie just beneath the everyday, carries over into his forays behind the camera: a 1975 documentary, We’re Not the Jet Set; the 1983 independent film Angelo, My Love, a documentary-inflected drama about a charismatic New York Gypsy boy and his world, which compensates for its rough construction with scenes of extraordinary behavioral observation; and his new film The Apostle, which Duvall wrote, directed, and plays the lead in, as a flawed but impassioned Texas evangelist who falls and reinvents himself to seek degree-zero redemption. This is a remarkable, fully realized vision of irrepressible spiritual exaltation—and incidentally a long-overdue corrective to the hypocritical, repressive born-again fanatic bogeyman so favored by good Hollywood liberals, a variant of which Duvall played years ago in M*A*S*H. The Apostle carefully balances and harmonizes the demands of dramatic narrative against Duvall’s own fervent commitment: to the truth of the moment and the life of the characters, his lifelong calling.

The Apostle

What inspired The Apostle?

I’ve just always wanted to play one of these preachers. Many years ago when I was in Arkansas, just wandering around, I saw preachers who had music around them, a guy on a guitar, and this kind of thing has always interested me. There was a [project] called The Kingdom; Sidney Lumet was gonna direct and Mamet was gonna do rewrites—a strange duo for this subject. Hollywood said I wasn’t right for it. The two guys who wrote the script approached Horton Foote after it fell through and asked him if he could help revive it: “Could you talk Bob Duvall into playing the lead, because we wrote it for him?” Horton said, “Well, Bobby’s doing his own script since that’s fallen through.” I’d gone once a month for ten months to Texas, stayed with friends and went to all kinds of churches doing research. Because of the whole sense of being in that community, really trying to immerse myself, sop it up and learn stuff, when The Kingdom fell through I just kept going.

What would The Kingdom have been about?

As I remember, it was about two preachers, different aspects in their whole approach. It was a pretty good script.

Were they grassroots preachers?

They came from grassroots, but there’s a contamination process that seems to set in with some of these preachers once they get into that nouvelle-riche realm, television or whatever; they can really become insufferable in their self-righteousness. It’s a joke. Within the nucleus of this movement, there are some very sincere, honest people. But maybe they couldn’t handle it when they got this sudden power; I don’t know, maybe some of them don’t even want it. The thrill of it is to try to show this world the way it should be shown.

I saw clips of Elmer Gantry and it was all patronization time by Hollywood, putting forth caricatures and these quick, easy images of what really isn’t. So that’s an education process. When people would say, “Are you gonna make your guy this way?”, I said, no, he’s an honest guy who lives what he believes, but he has weaknesses like anybody else, hypocrisy … no more nor less than any Hollywood producer or guy that runs a studio who are making the decisions about this.

I called up Harry Crews, the novelist, a very talented guy. He wrote one script that was okay, but then I figured, he’s gonna write a script and explore those people—what if it goes so far in one direction that I don’t know how to pull it back? I’ve gotta jump in and do my own. Horton Foote encouraged me.

I direct as an actor, as an extension of that; and I feel that whatever I may offer as a writer … I was a terrible writer in school, I don’t consider myself a writer. What I know and what I think I understand about behavior, what I look for in behavioral terms … because that’s what I’ve been doing for many years anyway, taking something that’s nothing more than ink and transforming it into behavior. Even though the concept may be there, it’s still ink.

What really got under your skin about playing a preacher?

An actor always looks for challenges, and this was a wonderful challenge, something I felt I could do. I’m not saying other actors couldn’t, but I felt I had a bead on this guy. It was very challenging in a titillating, alive way. I wanted to see if I could recreate the rhythms, the temperament, the whole makeup and aura of the guy. I was afraid of having to direct it, but Coppola, Ulu Grosbard, Richard Pearce all told me I should; they sensed I understood it maybe more than they would if I would have called them in to direct. I didn’t wanna come up with an indictment or a critique of these people—I wanted something from their point of view. From within their midst but not really of them. To come into that realm and take out of it and put forth what I feel is there.

The Apostle

That’s really an actor’s approach.

I think so. When I was in those churches I was very objective; I kept saying, I’m not really a part of this, yet I am but I’m not—I’m very cut off from it. But maybe that’s the way it had to be. I searched in a very enthusiastic and fun way, to really glean what I had to glean from it.

Did you ever feel swept up in it?

In the music, sometimes, the singing. One time in a very classic church in Harlem, the Metropolitan Opera Choir were singing “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” and a very quiet emotion came over me. I could count that as a conversion, if I were of this persuasion, but I just took it to be a very wonderful, personal feeling. I certainly could have counted it as a conversion if I had been looking to be converted. Sometimes people get swept up and that is very genuine; other times I think it’s a mass [psychology] thing, so the individual has to be careful.

In a sense, preaching is another uniquely American artform, like jazz or the Western. Was that important to you in how you related to it?

Very. I wanted to find the style of preaching and approximate that as well as I could, as I tried to in Tender Mercies with the singing. And that’s a big part of the infatuation for me. There was a line I took out of the script (because it got very long) where I said, “If preaching is in any part of my body, it’s in my blood and it’ll be there until the day I die and go to heaven.” And preachers are very good storytellers; I’ve been to churches where a guy will take one line from the Bible and then go on for an hour and a half, putting on almost impromptu plays or improvisations. When people give their tithes, it’s just their entertainment. They might shy away from saying that, but it’s true. It’s a form of entertainment for their spirituality.

I noticed there are a lot of jokes in the sermons in the film.

Oh yeah, there’s a lot of humor. They’re always keeping that audience alive.

There’s a cutaway after the accident scene at the start of the film where the girl’s hand moves. It seems to suggest some kind of miracle.

Definitely. When I first saw it, it gave me goosebumps. That was meant to be. [My character’s intervention] could be a miracle, or some working that’s very therapeutic. Maybe there’s something to the power of prayer. But he did say “one may live and one may die,” and the young man already speaks, and you see her lifeless. And then she does move her arm. And it just happens to be a nice spiritual payoff.

The Apostle

What directors have influenced you?

When people ask me that, they say, “You worked with Ron Howard, you worked with this other person….” And I’ll say, “Well, Ken Loach.” That kind of stops them in their tracks, which I kind of like to do. That movie of his, Kes—it was like, when it came out, I was a little confused. It wasn’t a documentary, I knew it was fiction, but…. Scorsese sometimes can do that, his New York films. And that Yugoslavian guy, Emir Kusturica—When Father Was Away On Business was stunning; he’s good with actors. Another film that was good was My Life As a Dog.

Weren’t you in one of Lasse Hallström’s films?

Yeah, [Something to Talk About]; it was okay. I think sometimes when those guys come over here, they miss the point. That’s why Kenneth Loach doesn’t come: he’s smart, plus he doesn’t want to work here anyway. I tried to get him to come direct Tender Mercies, but he didn’t want to, which I can understand. He liked my Gypsy film very much, which I sent to him. I met him once for coffee, and we talked a few times on the phone. I asked him if he knew a good writer to write a soccer script, set in northern England. Someday I’d like to play a soccer coach, an over-the-hill soccer player; that’s been in the back of my mind for awhile.

Which directors that you’ve worked with have had the most influence on you as a director?

Ulu Grosbard on stage and in True Confessions, very much so. Coppola in a different way: he’s more of a literary guy than a behavior guy sometimes, but I watched one of those behind-the-scenes documentaries and I realized he knew a lot about acting. He said to an actor, “I don’t care where you end up, just go.” A guy like Kenneth Loach or Scorsese or Ulu Grosbard helps you by setting the atmosphere, and then it comes through you anyway. I’ve seen actors who’ve worked with these guys be not nearly as good under other auspices. People say “bigger than life,” but nothing’s bigger than life. And now people are stuck on this term “over the top.” Granted, sometimes there are people with big personalities—and they’re not over the top, their temperament is such that that’s what it is. You play within the confines of the temperament—it’s going to be big at times and not over the top.

When you’re directing and acting in the moment, do you sacrifice anything as an actor?

Maybe not in this situation [The Apostle]. Maybe I could have used help—you never know what another eye might bring. I’ve worked with wonderful directors, and usually you know when the take is good, and they know when the take is good. You look at them, they look at you; you’re pretty much on the same wavelength if you’re working in the same way. I know when it’s okay. I worked with a crazy Polish director, Jerzy Skolimowski [on The Lightship], and he said, “In directing yourself, you prepare the whole situation and then at the last minute you step in front of the camera.” That’s kind of the way it was. I kept telling everybody it was just like a line rehearsal, just a simple throw-it-away, nothing’s precious, make it offhand so it’s like life; and that way I could arrive at a sense of behavior that was like life within picture time, instead of having to act out concepts and let’s sit down and rehearse—that can be dangerous unless the director really knows what he’s doing. So we just kinda went with it each day. And that’s the way I work as an actor myself.

Apocalypse Now

But aren’t there other things the director can do for an actor besides deciding if the take is good? A director may say something to an actor just before the cameras roll that gives them something they wouldn’t have had.

It doesn’t happen often. I’m sure that it’s happened to me—in a bad way more than a good way. Sometimes you want to say, “Please guys, back up—let me do it, otherwise you put on the costume and you do it.” The best directors I’ve worked with leave you alone. Maybe they’ll tell you something, say, “You wanna try another one?” And without too much direction, just by trying another one, something might happen. A guy like Kenneth Loach arrives at things through improvisation, and therefore you both find the way you want to go instead of just results. Going for results can be dangerous.

But I know what you’re saying. On True Confessions Ulu Grosbard said, “You don’t have to worry about getting anywhere, just see where it goes, forget about energy.” Usually it’s the other way round—directors want [snapping fingers] energy, pace—which is what’s wrong with so many movies: you just see everybody up there trying to do something.

A wonderful director like Stanley Kubrick—some of the worst acting performances in the history of cinema are in his movies. The guy that’s coming back, Terry Malick, you see nice performances, so it depends on who that somebody is.

Are you as an actor in any way dependent on the director?

Yeah, you rely on the director to let you alone and see what you do. A lot of times when it’s warfare it can still come out okay—it’s a resistance thing. But it’s better when you’re on the same wavelength.

Read Gavin Smith’s entire interview with Robert Duvall in the November/December 1997 issue.