A Double Life

To begin, a personal note: from It’s a Wonderful Life to Eyes Wide Shut, it is the melancholy and dark visions of Christmas in cinema that have meant the most to me. No doubt this has something to do with my own first experience of Christmas in America as a new immigrant, a couple of decades ago, when I was in my early twenties. Having arrived from India, to a land where I did not know a soul, all holidays were occasions to be dreaded. None was more dismal than my first Christmas, spent wandering the empty, chilly streets of my newly adopted city of Buffalo, New York.

And so I felt both recognition and solace upon encountering Jonas Mekas’s Lost Lost Lost (1976), in which he recalls the piercing loneliness of walking through the streets of Manhattan and Brooklyn as a recent immigrant, especially during Christmastime. One of the first title cards in Mekas’s epic diary film reads, “DPs arrive in America”; the displaced persons in question are Lithuanian-born Jonas and his brother Adolfas, who land in New York in 1949 after having spent years in assorted displaced persons camps in Europe. A complex and layered work, Lost Lost Lost—especially its first hour—is among cinema’s most poignant accounts of the immigrant experience. During those first two reels, Mekas chronicles four years spent amid the Lithuanian exile community in Williamsburg—a period that began with a strong belief in the “myth of return” to the homeland, and ended with the crushing realization that this would never come to pass. The Mekas Brothers then picked up and moved to Manhattan in 1953, resigned to building a new life in America.

Although Mekas bought his first 16mm Bolex camera on borrowed money the week he arrived on these shores (and began filming right away), more than 20 years were to pass before he could bring himself to assemble the footage and add narration to produce the final work. This gap in time proved crucial: it results in a reflective distance that adds to the film’s emotional power. “Since no place was really his home,” he remarks on his exiled self, in his halting, poetic, and accented voiceover, “he had the habit of attaching himself immediately to any place. He used to joke: drop me in the desert and come back next week—and you will find me. I’ll have my roots deep and wide.” This desperate search for settled-ness manifests for him as a heightened sensory awareness of the everyday, an impulse to seize and treasure the quickly passing moment.

Lost Lost Lost

Arriving when it did, my encounter with Lost Lost Lost radically altered my relationship to cinema. The role of art, until that moment, had primarily been as a source of pleasure in my life. But now it became something more: it entered the innermost realms of my daily existence, and helped reconcile me to my dislocation. Most immediately, the Mekas film soothed me by providing a site of identification with the journey (both traumatic and adventurous) of a migrant, even if its particulars were far removed from my own. But more than this, it modeled for me, in epic detail, a response to the challenges of a life stranded—profoundly divided, on every level of body and mind, between native and adopted lands.

Historically, the best immigration cinema stages, in an astonishing multitude of ways, a divided state of being. By this I mean a condition not just limited to the subjectivities of specific characters—although it does find widespread expression there. In the most successful works, it infiltrates film form itself, often incarnated in structuring and stylistic strategies (breaks, doublings, oppositions) that echo the “split immigrant self” and its experience in the world. This idea is not new: scholar Hamid Naficy has coined a useful term, “accented cinema,” to describe works by directors who are exiles, migrants, or diasporic people. These are films marked by a “double consciousness” that finds itself divided between cultures. But rather than limiting the idea only to the work of certain filmmakers (based on their biographical particularity), it is possible to extend it to all immigration cinema. This opens up a broad field—admittedly non-comprehensive—that might span the silent period to the present.

Charlie Chaplin’s The Immigrant, one of his most iconic works, is an opportune starting point for our survey, having just turned 100 this year. Reportedly his personal favorite of the 12 two-reelers he made for Mutual, it is comprised of two long sequences. The first half is set onboard a ship carrying immigrants in steerage to America; and the second takes place in a restaurant where the penniless Charlie tries every trick in the book to outwit an intimidating waiter. Chaplin himself had emigrated a mere four years earlier, and both sequences contain startling touches of realism. In a great subversive stroke, we see the ship’s passengers glimpsing the Statue of Liberty for the first time, and being moved by it—but their spell is quickly broken by immigration officials, who begin herding them like animals. (The film, among others, was later cited as evidence of Chaplin’s “anti-Americanism” during the McCarthy era, and he was forced into exile in 1952.)

Even in this brief work, Charlie’s Little Tramp character is conceptualized with clarity: he has two distinct sides to him, and can turn on a dime from one to the other. Hardscrabble immigrant Charlie is vigilant, streetwise, and a cunning gambler; romantic Charlie is a sensitive and thoughtful suitor, making a secret gift of his poker winnings to the woman he loves. The trials of immigrant life have made him resourceful and clever, but they have not expunged his inner core of tenderness. This duality is mirrored by the movie’s genre status: both a “social problem film” about suffering, impoverished immigrants and an ingenious romantic comedy.

The first decade of the sound era produced a true migration classic (and forerunner of neorealism) in Jean Renoir’s Toni (1935). It opens with a train arriving in the south of France, bringing new immigrants. Two railroad workers complain, “They are taking the bread out of our mouths!”—only to sheepishly admit that they themselves emigrated from Spain and Italy. This is a wonderful touch, for two reasons: it realistically captures the occasional ambivalence of immigrants toward their own kind, and it also illustrates a theory Renoir liked to advance—that horizontal class solidarity frequently wins out over other divisions, such as those of ethnicity or nation.

Nevertheless, Toni is what today would be called an “intersectional” work. In the film, laborers of varying national origin work side by side, forming earthy and easy relationships with each other. (Alas, these bonds are literally fraternal, as this camaraderie occurs almost exclusively between men.) The scholar Edward Ousselin has analyzed the film’s multilingualism, noting that the dialogue weaves in and out of at least three languages—French, Spanish, and Italian—along with the intermittent diegetic appearance of a musician who sings in Corsican. Renoir’s use of direct sound also crucially enhances the sensory effect of this heterogeneity.

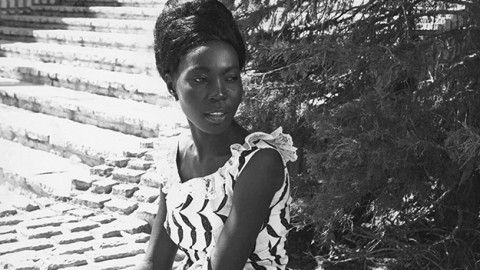

Black Girl

A few years later came World War II, and with it, the kinds of mass displacement experienced by Mekas. Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli (1950) begins in a DP camp in which the air is filled with voices of varied accents. The serially displaced Karin (Ingrid Bergman) has made her way from her native Lithuania to Yugoslavia and finally to Italy, all on false ID papers. When she is denied a visa to Argentina, she immediately (and opportunistically) marries a Sicilian fisherman (Mario Vitale, a real-life fisherman and nonprofessional actor) who takes her back home to the volcanic island of the film’s title. Rossellini examines her difficult path to tentative acceptance of a new land and culture. The movie conveys a powerful sense of Karin’s confrontation with otherness—not just human, but a totality that includes the entire natural environment. Rossellini was famously committed to rooting his films in documentary authenticity (“Things are there. Why manipulate them?”), and the fact of location shooting gives the images a powerful charge, making us share in Karin’s alienation and anxiety. Migration in movies generally takes place from less to more prosperous lands, but Stromboli inverts this movement, exacerbating the strangeness of the encounter through inspired casting. Bergman’s tall, Nordic presence is conspicuously out of place on this sweltering island whose inhabitants (played mostly by locals) are short, dark-haired, and olive-skinned.

The decades following WWII witnessed gradual decolonization, especially in Asia and Africa, but it is the dark and enduring legacy of the colonial era that is at the heart of Ousmane Sembène’s Black Girl (1966). Its title character Diouana (M’Bissine Thérèse Diop) is a young woman who travels from Senegal to the French Riviera town of Antibes to live with and serve a white bourgeois family. Seduced from afar by images of material comfort in French magazines, she soon discovers that she is virtually a slave and prisoner in the apartment: “For me, France is the kitchen, the living room, the bathroom, and my bedroom.” Her acute alienation is exacerbated by her illiteracy. When she receives a letter from her mother, her employer reads it out loud to her and—in a breathtaking appropriation of voice—fabricates and sends a reply. Formally confident (in a decade that saw cinematic “new waves” springing up all over the world), Sembène’s visual design consistently counterposes black against white, dark against light. The majestic Diouana is usually foregrounded, while the nearly bare white walls of the sterile, modernist apartment form the enveloping background. Near film’s end, the image of a clean, white bathroom tub strikes a note of pure horror.

In addition to its aesthetic power, Black Girl has also proved prophetic. With the rise of globalization, millions of women from poor countries have migrated to the global north to become domestic workers. In earlier times of imperialism, Western nations extracted vast wealth and physical resources from their colonies. But today, as social critics Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Hochschild argue, another form of extraction is underway: a global transfer of female physical and emotional labor to rich countries. As if in anticipatory response, Black Girl closes with a brilliant reverse movement: an African mask, gifted by Diouana to her employer, returns along with her possessions to her mother’s home in Dakar. In Sembène’s hands, this poetically charged object carries the full spiritual weight of Africa. In the film’s eerie final sequence, the mask takes on a life of its own, literally stalking and chasing away the colonizer.

The early 1970s witnessed the rise of the women’s movement and second-wave feminism, which quietly mark Joan Micklin Silver’s Hester Street (1975). It was a courageous undertaking: independently financed, shot in black and white to stay true to its visual inspiration (photographs of the Lower East Side by Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis), and featuring much subtitled dialogue in Yiddish—all risky box-office decisions. The film concerns a Russian-Jewish couple struggling with the anxieties of assimilation in late 19th-century New York. Basing her film on a short story by Abraham Cahan in which the husband is the principal character, Silver switches focus to the wife (marvelously played by Carol Kane). This decision allows for a keen opposition: between a faithful, period-specific depiction of tradition and a deeply sympathetic account of coming to feminist consciousness. The story builds to a bold climax—a traditional Jewish divorce ritual rendered in extended detail, patriarchal touches and all. Daniel Kremer, a filmmaker who is writing a biography of Silver, has called the movie a model instance of the “cinema of the pilpul”—after the Yiddish word for compromise—because it captures the dynamic of alternately resisting and yielding to the forces of cultural assimilation. (Yiddish itself reflects these forces, being an amalgam of Hebrew, German, Russian, and other Slavic languages.)

Another instance of New York migrant cinema, Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1976) is exclusively composed of 16mm contemporary footage of the city: mostly static-camera, long-duration shots of streets, storefronts, or subways. But the voiceover consists of letters, written five years earlier by her mother Natalia from Belgium. In a further displacement, it is the filmmaker’s voice (not Natalia’s) that we hear reading the letters. Akerman’s cinema has always been formidable for the way it sets up structured oppositions in order to mine the tensions that they hold. She once explained, in an interview with Gary Indiana, how extended duration inspires the viewer to look in a particular way: oscillating between information and abstraction, each enhancing the other. While that dynamic operates in all her films, News from Home features another provocative split: between the private nature of the letters and the public spaces captured on the image track. The intimacy and longing in Natalia’s words brushes up against implacable shots of strangers on city streets. New York is vividly present—thanks to Akerman’s documentary images from a storied era—but the city is also rendered a touch remote by the aloof camera. Both voice and image slide between absence and presence.

The 1980s was a decade of political repression in Central America, which provides the context for the low-budget, independent drama El Norte (1983), directed by Gregory Nava and produced by co-writer Anna Thomas. As novelist Héctor Tobar has pointed out, the film departs from the longstanding “Graham Greene formula” (both literary and cinematic) of centering white Westerners in narratives set amid Third World political conflict. The protagonists here are two indigenous Mayan teenage siblings who flee persecution in Guatemala to Mexico and then Los Angeles, finding precarious, undocumented work there. For most of its length, El Norte works in a social-realist mode, politically commendable if aesthetically unexciting. But occasionally, this staid surface is punctured by brief flights of magical realism when all the pain and yearning of exile flash up in evocative images. Their poignant affect lingers, long after the conventional plot mechanics have faded from memory.

El Norte

The stately 35mm images of El Norte are a world apart from the rough-textured home-movie footage of Sandhya Suri’s family memoir/documentary I for India (2005)—nevertheless one of immigration cinema’s hidden gems. The filmmaker’s father, Yash, a doctor, emigrated with his wife and children from Punjab to England in 1965. Wanting to stay in close contact with his parents and siblings, he purchased two Super-8 cameras, two projectors, and two reel-to-reel tape recorders. He shipped one set to Punjab and kept the other. He then made films of his family’s new life, recording audiotapes to go with them, and mailed them home; his brother in India reciprocated, thus inaugurating an epistolary relationship that would span decades. The filmmaker draws from this archive of home recordings to tell her family’s story, moving back and forth in perspective between home and host countries. I for India dramatizes a wrenching and permanent ambivalence at the heart of migrant life. On the one hand, the typical immigrant seeks out and welcomes opportunities in the new land; but on the other, she often despairs over both racism and a feeling of having been severed from her homeland—even taking on a weight of responsibility for this separation. Adding to the heartbreak is the film’s view of immigration as repeated displacement: alienation causes the family or its individual members to pick up and move recurrently, a measure that fails to necessarily bring restoration or healing. As I both enjoyed and endured an itinerant childhood—my father’s wanderlust sweeping us up and setting us down in a new city nearly every year—I for India’s interest in this theme carries a special charge for me.

In the last couple of decades, every worthy film made about immigration has been marked, to one degree or another, by a crucial phenomenon: the ascendancy of neoliberal capitalism. Christian Petzold’s thorny and complex Jerichow (2008) melds the global and the local—capitalism and the fallout from German reunification—by using as a template the classic 1946 noir The Postman Always Rings Twice. Its narrative draws a triangle between Turkish entrepreneur Ali (named for that icon of immigrant cinema from Fassbinder’s 1974 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul) and two ethnic Germans—his wife Laura, and her lover (and his employee) Thomas, who hatch a plot to murder him. Part of Jerichow’s appeal lies in its meta-cinematic move, the way it inserts itself as a kind of corrective into a particular lineage of film history. In the last few decades, as Jaimey Fisher argues in his valuable book on Petzold, there have been primarily two kinds of German movies on the subject of immigrants: the “guest-worker film,” which highlights the economic and racial challenges they face; and the “ghetto film,” revolving around criminality and influenced by transatlantic forebears like Boyz n the Hood (1991). The former belongs to a patronizing “cinema of duty,” while the latter no less participates in creating a hierarchical view of society with firm lines drawn between ethnic Germans and non-Germans. Jerichow (Fisher shows) dismantles this binary condition. Its three characters have a “horizontal” if complicated relationship; the immigrant is morally imperfect, remains unromanticized, but nevertheless becomes a tragic figure by the end. The depressed town that gives the film its title is located in the former East Germany, and every step of the way, what ties the three characters together and governs their actions is brute economic logic. As Laura puts it succinctly to Thomas: “You can’t love if you don’t have money.”

In addition to economic difficulty, the immigrant also faces special challenges of mobility. While neoliberalism trumpets the ideology of freedom—markets must be free, and so must the global flow of capital and goods—it does not extend this freedom to the movement of people around the world. We witness the harsh effects of this double standard in Mediterranea (2015), in which two friends from Burkina Faso travel to Libya and then across the water to Italy, enduring myriad hardships along the way. Once there, they struggle to find work and encounter racial hostility. The film’s title renders the Italian word for Mediterranean in plural form, thus denoting a geographical zone that migratory flows have transformed into multiple, contested spaces. Italian-American director Jonas Carpignano draws subtle links with an earlier wave of immigration—from Sicily to America a century ago, when letters written home played a key role in sparking the desire to emigrate. The film proposes Facebook as a contemporary equivalent; we see the way in which status updates and videos exert a pull, fueling immigrant fantasies from afar. Migration movies are often preoccupied with specifics of place, and three environments predominate, in succession, here: a scorching desert in Algeria; the inky, menacing waters of the Mediterranean; and a run-down agricultural town in Calabria. Over these starkly different spaces is overlaid a Dardennes-like cinematic style that favors close-ups and movements of camera in tune with human bodies.

The Future Perfect

Besides movement, another key theme is becoming apparent in new films about the migrant experience: the importance of language, not only as an instrument of survival but also as a means of building identity. It is a concern that is movingly and creatively explored by two recent works, Fatima (2015) and The Future Perfect (2016). Philippe Faucon, director of the former, is a Pied-Noir of mixed French and Algerian descent who makes understated but perceptive cross-cultural cinema. Fatima’s title character is a North African immigrant mother in Lyon (indelibly played by Soria Zeroual), divorced and working as a cleaning woman; she is also raising two teenage daughters markedly different in personality. One is single-mindedly devoted to her medical-school education, her desire to prove herself owing no small part to her status as a second-generation immigrant and woman of color; and the other is a rootless and cynical high-school student. When Fatima converses with her daughters, she speaks in Arabic but they speak in French. (The subtitles don’t make this distinction, which has the effect of sharpening our auditory attention as the film unfolds.) Facing great difficulty in communicating with—and gaining the respect of—her younger daughter, Fatima takes up French-language classes, which has the side effect of unlocking a passion for writing poems and prose in Arabic. (Faucon adapted the film from a memoir by Moroccan writer Fatima Elayoubi.) Admirable is the quiet but sustained bilingual/bicultural emphasis, and the focus on the three women; the father pops up occasionally but the movie does not give him a name (a nice touch).

If Fatima works in a realist mode, Nele Wohlatz’s The Future Perfect is a stylized, elliptical comedy about how identity emerges through language. A Chinese teenager (Xiaobin Zhang) arrives in Buenos Aires to join her family, but her meager Spanish makes it difficult for her to hold down a job. She enrolls in a language class with other Chinese teens, and they learn by role-playing characters and scenarios. As her language proficiency grows, so do her self-confidence, her social life, and her imaginative powers. Wohlatz, a German transplanted to Argentina, was driven by a conceptually original impetus: to make a film that was “scripted by language books”—one that approaches a language school as a space that is theatrical/fictional, a “rehearsal stage for a new identity after immigration.” The students in the class are played by young Chinese non-actors in Buenos Aires whom she discovered when they performed a theater piece in Spanish; but more than their speech, she was struck by “the drama in their bodies,” an aspect foregrounded by all the intent close-ups in this lovely, gentle film.

Taken together, these two works (along with Aki Kaurismäki’s forthcoming The Other Side of Hope) represent a particular strand of immigration cinema that holds some promise for future films. They are small-scale movies that, in their modesty, shy away from the bold monumentality of Black Girl or Ali: Fear Eats the Soul or El Norte. Instead, their value lies in their attentive, microscopic focus on specific geographical/cultural pockets of migrant existence around the world. Without denying the universality of the challenges that immigrants face, they also work to de-universalize that experience, quietly teaching us about its immense variety—thus painting an ever more complex picture of a phenomenon that will surely be of central importance for the rest of this century.

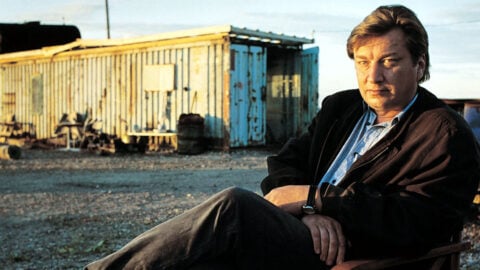

Girish Shambu teaches at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York, and is the author of The New Cinephilia.