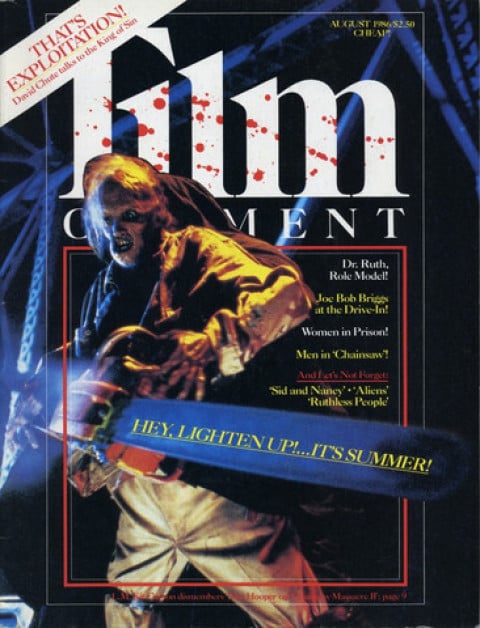

‘Saw’ Thru

I’m always looking for a harder, nastier, crazier sling in the work. One you can taste.

—Tobe Hooper

EEEWWoaoaoaaaaooooonnnnaaaaaeeeeyyyiiiiiiAAAAAAAYYYaaahh...

“This one line of dialogue goes on for about the last 23 minutes of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (aka ’Saw 1),” says Tobe Hooper, who directed it. “It covers the infamous, excruciating Dinner Table Sequence (which was filmed nonstop for 36 hours straight until the last pennies of the $160,000 budget ran out). It may be the longest solid scream-track ever to shake out darkened American movie houses.”

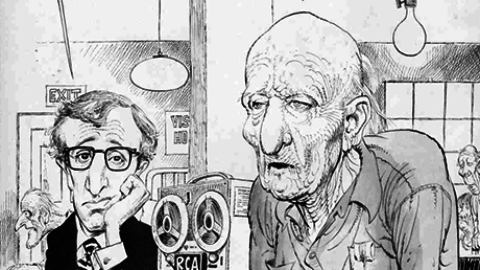

I first squirmed through it back in 1975 in a tiny, dumpy screening room just below Sunset Boulevard. I was newly exiled from Texas and had known Tobe Hooper as a good documentary filmmaker (Peter, Paul, and Mary in Concert, 71) in Austin but had no way to be prepared for the bite of The Saw. I flat couldn’t take it—neither could Paul Schrader, a curious friend who’d come along to the screening; about midway through the movie we buzzed the projectionist to skip a couple of reels and just show us the end. Whu: this sucker could really hurt you.

Post-screening, blinking in the daylight leaning on our cars, Schrader and I tried to figure out what we’d run into.

Brian De Palma and George Romero had only recently corkscrewed fresh blood into the horror genre (Sisters, Night of the Living Dead); but they were sophisto guys who’d kept the “it’s-only-a-movie” deal with the audience. Hooper was a new deal—simply this: no deal. Hooper was a scare-director who was methodically unsafe, who the audience (you) finally just couldn’t trust. Kind of like Life Its Ownself. He’d go too far, then go farther, and go farther, and go farther again, and kick it again, and then it’s over, then get in an extra kick, then it’s over… then one more kick…

“I was a fanatic film fan from before birth. My mother had to be taken out of the State Theatre in Austin straight to the hospital in labor. Probably it was one of those good, good black-and-white Michael Curtiz pictures she didn’t want to leave. My mother and father loved movies. As soon as I was out of the hospital, I was taken with them to the movies. And I literally grew up in the movies.”

Hooper spent his first two years in Austin. His father had a crackerbox-shaped limestone hotel on Congress, the main street, about four blocks from the Texas State Capitol building. The hotel was squared on all four sides by moviehouses (the Paramount, the State, the Queen, the Capitol) whose marquees changed every other day in the wartime Forties so there was a new movie to see every day. Hooper wet-nursed on three, four movies a day, plus cartoons.

“I can remember my first 6mm lens-shot looking up out of the crib at the shadows dancing on the ceiling. At the same time I was learning to talk, I was learning to see everything in camera coverage: wide shots, close-ups, etc. I didn’t exactly know I did this until I was about 20: one evening outside San Francisco I was watching the Pacific Ocean from a Cliffside—suddenly the Panavision aperture in my head widened and went away. And I realized that all those damn years I’d been shooting movies, with and without a camera.”

At age 4, Hooper made his first with camera shot: XCU of a small bronze horse statue he now keeps on a shelf in his living room. Then he started shooting hundreds of 8mm mimic-movies on $5 budgets casting cousins and friends, using a war-surplus three-lens Bell & Howell spring-wind camera.

By 10, Hooper had decided (after toying with the notion of being a mad scientist) to be a director. The grade school principal had called him into the office and warned that his classmates were weirded-out by Hooper’s movienutness. Too late, Mr. Principal: Hooper was cranking out a new movie nearly daily, showing them at his house—and charging the neighborhood 5¢ a head. The kid had found out about box office.

Last semi-Rosebud flashback: Hooper, like many brotherless/sisterless kids, collected special odd bunches of things. Maybe a way to fill up a solitary world. One collection was cigar boxes of burnt wooden matches. “Yeh, I used to pick ’em up all around in ashtrays and save ’em,” Hooper shakes his head. “Don’t know why. I think I thought they looked lonely.” Lonely burnt matches? Check Man and His Symbols.

Odds For The Future

“After my folks split up, I lived with my mother. But my father became terminally ill when I was a teenager, and I moved to Grand Prairie [near Dallas] to be with him for his last four years. There I made my first 16mm film, $1100 budget, called The Abyss. Things were kind of dark around me in those days watching my father dying.”

After his father’s death, Hooper returned to Austin and into the University of Texas Film Department (population, 2: Tobe Hooper and the Film Instructor).

Hooper got a part-time job making 20-minute sales-tool shorts for a local insurance company—insidious little dramas to pitch fear into families. Like what happens after Dad gets mashed to death in a three-car accident: lose the home; the dog runs away; finally the 12-year-old daughter hits the streets hooking. Like what are the Odds For The Future: a hundred little golden plaster of Paris men standing on a wonderful wide horizon; 95 of these figures abruptly explode; that’s the odds; don’t bet on it, pal.

After he’d made almost 50 of these bum trips, Hooper got a call from the insurance company president congratulating him for helping to boost sales—plus a suggestion that Hooper start studying the obituary columns so he could go shoot telephoto footage of real grief-filled funerals. Hooper quit.

Then, unaccountably, the insurance prez called Hooper back. He had been truly impressed with Hooper’s work in scaring lots of money out of insurance buyers. He offered to bankroll a short film, no joke.

At 21, Hooper wrote and directed The Heisters, a 35mm 10-minute color comedy about three medieval outlaws who get into an absurdly escalated Road Runner–cartoony fight over their stolen booty. It won awards at the Tours, Cannes, and San Francisco film festivals. And for better or worse, it made Hooper a big shot in and around his hometown.

“I got a little bit swelled up—some people said I got so high and mighty that you couldn’t hit me in the ass with a red apple. Maybe so.”

Over the next eight years Hooper schemed up his future. He formed three film-production houses in Austin; shot industrials and documentaries for PBS, the Texas Highway Department, etc. Finally he pooled enough money and power to finance his first feature, Eggshells. It was about the breakdown of a commune, a slightly surreal, end-of-hippiedom love story. This movie was going to be Hooper’s ticket to Tomorrow. But this was 1972: spacey hippies were media-dead history; Nixon was in solid; Watergate was just a hotel. Eggshells got 50 play-dates. Minus-zero box office.

Hooper had forgotten the Odds For The Future.

’Saw 1

“One of the things messing with the audience in the ’Saw movies are these characters that get around and wallow around down in the grave and make artful objects out of brains and guts… This sort of messing gets connected to the persona of The Grand and Master of Monsters, The One and The Only—which is Death itself. The Grim Reaper.

“So in ’Saw 1 when I took hold and starred screwing around with this Chainsaw Family who’d snapped into the persona of Death, I was getting these horrendous shocks and jolts myself. Because that’s what gives me the creeps, gives me the willies: Death. And all the accoutrements and symbols of Death: the quilted satin, the shiny $22,000 coffin, embalming room, the moment when the lilies come. That stuff frightens me. I’m afraid of it.

“This crazy chainsaw bunch had an edge that couched me awfully deep down. And I felt if I held on and kept going I’d maybe touch nerves in the audience that are ordinarily covered up—ultimate subconscious, terribly disturbing, nasty, sticky fears of Death.

Eggshells’ smashup fried Hooper. Near broke at Christmas ’72, he got tangled in the last-minute-shopper mob at a Montgomery Ward and shoveled into the heavy equipment department—suddenly he was standing face to face with a big wall display of glinting chainsaws. All sizes. Row above row. An uneasy-making sight mixed with the tinsel, bright Christmas balls, red ribbons. Whu.

And an abrupt Christmas crackup thought flicker-lit a few of Hooper’s brainy synapses: Quickest damn way out of here tonight is just to yank-start one of those chainsaws and cut a path to the door. It was a joke, but only a half-joke. An image that sold itself a bit too strongly.

Hooper got the hell out of Montgomery Ward, went home with a chainsaw in his brain, and starred piecing together a movie. “In about 30 seconds I saw the movie right in front of me.”

He had part of a script about hippies in a haunted house. And he had some leftover childhood nightmares about a wacko Fifties mass murderer in Plainfield, Wisconsin, named Ed Gein—Gein had been the usual sweetheart handyman/babysitter type who also gutted and flayed drifters, made skin lamp shades, bone furniture, kept his freezer stacked with human hearts. (Hooper’s relatives knew folks from Plainfield and sometimes used to get a kick out of telling Hooper the kid booger stories about Ed Gein at bedtime.)

Hooper ran the hippies into the mass murderer and handed that booger a chainsaw. Bango.

“One other thing messing with the audience in the ’Saw movies is that these deadly Chainsaw brothers are funny. They’re funny as hell. And the audience gets that joke.

“I’ve noted this happen in screenings more and more often as the years go on. At some horrible, tragic moment when the last girl is facing death with these lunatic brothers bubbling and squabbling all around her, the audience starts laughing… then gets caught, catches itself… then starts feeling guilty for laughing… then starts laughing again at feeling guilty for laughing… So then the audience schizes right out not knowing what side of the fence they’re on: killers or victims? And intellectual/emotion ally, they get on both sides of the fence. Just to have it covered and be safe. And without realizing that, this way, they’ve made themselves completely unsafe and questionable as moral beings.

“It’s wild behavior. Seems involuntary. It’s another part of this movie that maybe touches people in places they may not want to be touched. Places they normally hide and shield.”

’Saw 2

Near Christmas ’85 Hooper asked me to consider the ’Saw sequel. He needed a yes or no by January 1 because the movie had already been slotted to open in 1800 movie houses on August 22.

Agents, lawyers, and pro movie-pals sneered lists of reasons for saying no:

1) Women-hating slasher sleaze yuk;

2) The Sequel-itis Curse;

3) Wipes your name right off the Serious Screenwriters’ Map;

4) No way to write-shoot-produce a real movie in seven months, etc.

I liked all the reasons (best: the Screenwriters’ Map, lemme see that map).

However, I’d worked with Hooper before (1978: Dead and Alive, a project now neatly dead on a shelf at Warners). I know Hooper has a trick for breaking in the back door to true strangeness, real madness. I know because he took me into that crazy place a few times during Dead and Alive—scared the hell outta me—yeh, Hooper’s got a trick not many people know. He stands there grinning, drinking a Dr. Pepper, and smoking a havana and says, “Y’ever been in Door Number 3?… You been in with The Lady. You been in with The Tiger… Don’t you wanna go in Door Number 3?” Spielberg tried to learn how to do that by producing Poltergeist; didn’t work.

“It’s important for a movie today to do more than tell a story, You’ve got to send a physical sensation through the audience and not let them off the hook.

“I like to just make it go faster and faster and faster and pumping and pumping and banging and banging until I get… in to you. Turn the visual and sound experience into a harmonic that mesmerizes the audience, cakes them right off into a hypnotic zone where they’re no longer thinking about how it’s done—they’re just there in a lucid place like those moments right before waking up. They’re just out there. Physically.

“I’d love to suspend an audience out like that for 90 minutes. Kubrick knows how to do it. You can come out of a good Kubrick movie different from the way you were when you went in. That’s what I’m going to try to do.”

Do ’Saw 2? You bet: it’s about croissants; it’s about chainsaws; it’s about to get you. Film Fall Footnote: I’ve still not seen all of ’Saw 1. Schrader claims he did watch it all the way through once locked in a car at a rundown drive-in outside Shreveport, Louisiana. He claims.