Russellmania!

In Lisztomania, Ken Russell’s 10th feature film, the Pope, played by Ringo Starr, refers to Richard Wagner as “anti-Christ . . . the Prince of Darkness.” Most critics would apply these epithets to Russell. Although Tommy was a critical as well as a commercial success (his first since Women in Love), much of the praise was decidedly backhanded; the critics accepted the film because they felt the material was trivial enough to benefit from madman Russell’s wild flourishes. Lisztomania, which has just gone into release, has revived all the old objections to Russell’s work. This colorful Looney Tunes version of the lives of Liszt and Wagner is the most outrageous, flamboyant film Russell has done; The Music Lovers looks positively Bressonian by comparison. Russell still polarizes his audiences. Although he is despised by the critics, his films are among those most frequently revived; he has a small but passionately devoted cult following.

As one of Russell’s original defenders, I am disturbed by the mindless adoration as well as by the hysterical outrage that greets his films. No one seems capable of approaching his movies openly but coolly; there is very little serious writing on his work. (The exceptions include John Baxter’s interview book, An Appalling Talent, and Michael Dempsey’s thoughtful article, “The World of Ken Russell,” Film Quarterly, Spring 1972.) Much of the antipathy that Russell’s films arouse is calculated. In an age when most of the traditional pieties have been blasted, what can possibly shock an educated audience? Art is one of the few subjects that critics and intellectuals regard with an almost religious reverence, and so Russell’s heretical revaluation of famous artists offends people. Although intoxicated by the power of art, Russell is harsh in his attack on the frailties and cruelties of the artist. In addition, he advances Freudian interpretations of art, seeking the sources of Tchaikovsky’s or Mahler’s music in childhood traumas and sexual fantasies; this psychoanalytic approach is intolerable to people who have come to believe in art as the one sacred mystery in an absurd and faithless world.

Stylistically Russell’s films also present problems to critics. His work depends on excess, and his films violate most of the formal rules taken for granted in naturalistic filmmaking. Over his last several films Russell has been moving further and further from realism into fantasy. In The Music Lovers, a fairly straightforward narrative is interrupted with a few fantasies and memories. Mahler, made three years later, still has a skeletal plot, but most of the movie is taken up with a complex montage of flashbacks and fantasies. In Tommy and Lisztomania, all distinctions between fantasy and reality have blurred. Russell’s work is closer to opera or lyric poetry than to traditional drama; he composes dream images charged with emotion that is not always under control.

The Boy Friend

The dismissal of Russell by many critics rests on an overly narrow understanding of what art should be—a limited definition that these critics would never think of applying to the other arts. Subtlety and restraint are the virtues of a Henry James novel, but they are hardly the terms of praise one would apply to the novels of Dickens or Lawrence, or the paintings of van Gogh. Russell’s work is notable for its intensity, ferocity, and imaginative boldness rather than for its subtle nuance, its psychological depth, or its intellectual acuteness. In a famous remark, Dr. Johnson described the imagery of the 17th-century metaphysical poets: “the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.” The electricity of Ken Russell’s tense, unstable lyrics comes from a comparable juxtaposition of opposite or discordant emotions; he shows little interest in the gray area in between the extremes.

Like many artists, Russell seems to operate on a mixture of calculation and intuition. He often plans his visual effects with meticulous care. Yet he has also said, “I’m a great believer in not always knowing why I do things, and not always being able to explain them.” Huw Weldon, Russell’s producer at the BBC (where he made over 30 documentaries between 1959 and 1970), told John Baxter, “In terms of invention and the leap of the mind, it isn’t that he leaves me behind; he leaves me standing. On the other hand the capacity to analyze and rationalize Ken doesn’t begin to have.”

Nevertheless, even Russell’s bitterest enemies would not deny that he has his own distinctive vision. His baroque visual effects are easily identifiable, and he has developed a transient repertory company of actors whom he uses in film after film (a group that includes Oliver Reed, Glenda Jackson, Christopher Gable, Michael Gough, Kenneth Colley, Georgina Hale, and Murray Melvin). Characters and episodes from one film are re-interpreted later. One scene that Russell invented for Women in Love, in which Gudrun and the German sculptor Loerke pretend to be Tchaikovsky and his bride on their honeymoon, is like a dress rehearsal for The Music Lovers. In one outrageous fantasy sequence in Mahler, Cosima Wagner, dressed like a Nazi Brunhilde, presides over the conversion of the composer. Later, in Lisztomania, we see Cosima as Wagner’s child-bride, promising to keep his dubious theories alive after his death. The weird Nazi symbols of Mahler (which also figured prominently in Russell’s television film on Richard Strauss, The Dance of the Seven Veils), run riot in Lisztomania.

Mahler

These relatively simple connecting links point to a more comprehensive thematic unity. Many of Russell’s obsessions can be traced to his television films. One of the quintessential Russell images appears in Dante’s Inferno, his film on Dante Gabriel Rossetti, when the poet, who has buried a volume of poetry with his first wife, goes to dig up the coffin and retrieve the poems—art snatched (quite literally) from the jaws of death. Russell is haunted by images of physical and mental disintegration; the tension between art and death accounts for much of the dramatic power of his films. In The Music Lovers, Tchaikovsky hears a fragment of a song that reminds him of his mother; he follows the song to its source—a woman singing in a bathtub—and remembers his mother thrown into a boiling bath, her body ravaged by cholera; the music is helpless to exorcise this ghastly vision of death. A key sequence in Savage Messiah presents a different conclusion: after promising a wealthy art dealer a sculpture by the next morning, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska must steal a tombstone from a cemetery and spend the entire night chiseling a figure from the stone. In this case the artist’s effort to defy death is triumphantly successful.

Although Russell sympathizes with the struggle to transcend death, he wants to expose the artist’s ruthlessness in pursuing his vision. In his eloquent television film Song of Summer, focusing on the relationship of Frederick Delius and Eric Fenby, a young music student who comes to transcribe his last works, Russell introduces another of his major themes: the sacrifice of a weaker individual to the overweening ego of the artist. Young Fenby’s identity is destroyed by his absorption in the dying Delius’s life. This theme is developed further in The Music Lovers. Tchaikovsky marries Nina because of her resemblance to the heroine of his opera, Eugene Onegin. When his narcissistic romantic dream turns into a nightmare, he abandons Nina and retreats into his own imaginative world, where he is in full control. Tchaikovsky’s rejection destroys Nina; his music survives at her expense. And this same drama is reworked in Mahler: Mahler smothers Alma’s musical talent and demands that she devote herself to him. Since Alma is stronger than Nina, her life is not destroyed, but a promising career is aborted.

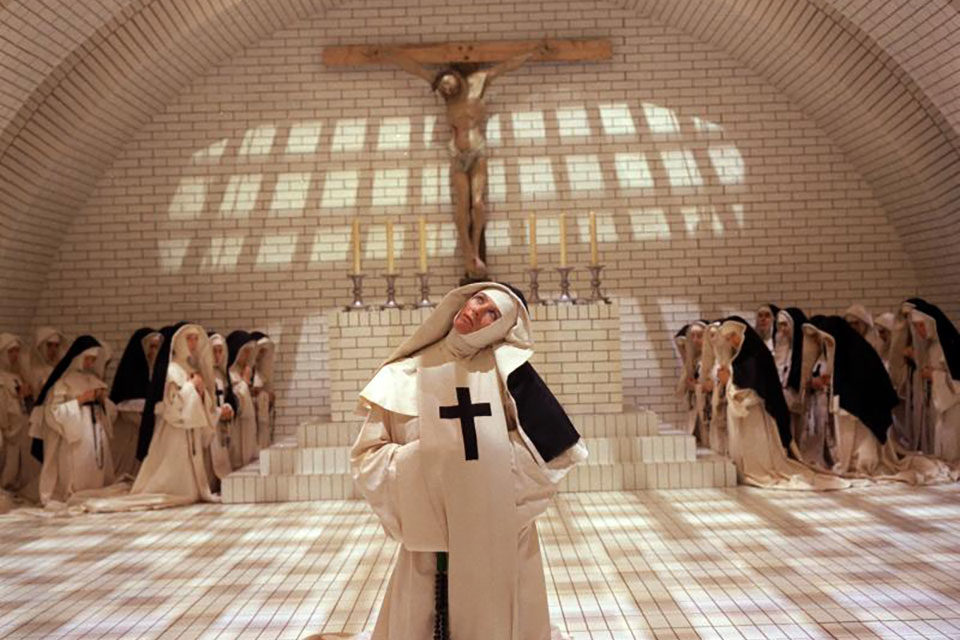

Russell’s investigation of the moral failure of the artist is a major theme of his work, a theme explored most caustically in Lisztomania. The films of Russell that do not deal primarily with artists—Billion Dollar Brain, The Boy Friend, Tommy, even Women in Love—seem less characteristic, less urgent. The Devils occupies a more important position, partly because of its Catholic theme (Russell is a convert to Catholicism) but also because the radical priest, Grandier, is a heroic, tormented figure involved in the same kind of agonized struggle against death as the artist. Although The Devils has a stronger political subtext than most of Russell’s films, he has very little interest in social and political issues, and that helps to explain what is missing from his striking but unsatisfying Women in Love. Russell does not begin to understand Lawrence’s profoundly comprehensive vision of the Industrial Revolution and the class struggle; the images of poverty (like Gerald’s white limousine moving through a line of blackened miners) are beautifully composed, but without the undercurrent of compassion and rage that animated the novel.

In spite of this failure, Women in Love was rightly praised for its startling sexual imagery, and for the superb performance of Glenda Jackson as Gudrun, one of the predatory female characters that fascinate Russell (just as they fascinated Lawrence). The Music Lovers, however, is Russell’s first fully characteristic feature, and the critics who were enchanted by the relatively faithful adaptation of Women in Love were not prepared for Russell’s sacrilegious treatment of Tchaikovsky’s life and music. The film is a pointed study of the decay of the 19th-century romanticism. At times the sensuous images and the soaring music reflect the breathtaking boldness and confidence of Tchaikovsky’s aspirations, but there is usually a tinge of irony qualifying the composer’s rapture. The images of idyllic family life that accompany the First Piano Concerto are luxurious, yet deliberately overripe. Russell sets Tchaikovsky’s ethereal fantasies against the harsh reality of his disastrous marriage to Nina, underscoring the composer’s narcissism, his carelessness toward others, and the destructive consequences of his immersion in dreams. At the conclusion of the film Russell composes stark, horrifying images of the madhouse where Nina is confined, in order to accentuate the force of the world that Tchaikovsky’s music ignores. Although precariously balanced between beauty and decay, romance and sexual nightmare, The Music Lovers ends with a harsh nihilistic vision of the triumph of chaos.

The Music Lovers

The Music Lovers feels like an exorcism of Russell’s own fears. Savage Messiah is a sunnier companion piece, a more wholehearted tribute to the adventurousness of the romantic artist. It contains many of the same tensions as The Music Lovers, but it is a more jubilant work, with only a few muted reminders of the artist’s delusions. One reason for Russell’s more sympathetic treatment of the French Vorticist sculptor, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, is that he died at the age of 23, before he had a chance to compromise.

Gaudier is a romantic who does not withdraw to a rarefied fantasy world. In London he works on a construction crew and lives in a hovel separated from the street by an iron gate; his proximity to the teeming street life suggests his willingness to confront the squalid world that Tchaikovsky flees. But like Tchaikovsky, Gaudier believes in the supremacy of his own imaginative vision, and this time Russell celebrates his arrogance and audacity. Gaudier stands for all the experimental artists of the modern age, impatient wit h tradition, eager to break taboos and live their daily lives with the same intensity an d unconventionality that they bring to their art. Yet there are a few darker intimations even in this film. Russell cannot help observing that the same recklessness that fires Gaudier’s art drives him to his death on the battlefield; his passion has its self-destructive side. The ending of the film is disturbingly ambivalent. At a posthumous exhibition of Gaudier’ s work, the smooth, gliding camera movements capture the beauty of the sculptures. In an earlier scene Gaudier said that art could not exist without an audience; yet the audience at his exhibition consists mainly of dilettantes who are titillated by his daring. The ending is a rousing tribute to Gaudier’s art, shadowed by a nagging, barely perceptible sense of futility.

This ambiguous conclusion does not dispel the exuberant mood of Savage Messiah, but it suggests that Russell’s vision of artistic fulfillment is always double-edged; he has a romantic spirit clouded by a sneaking sense of irony. Nevertheless, Savage Messiah is Russell’s most relaxed and affectionate film, and possibly his best—less sensational, more evenhanded, mellow, and mature than anything else he has done in features: it recalls his fine films on Delius and Isadora Duncan for the BBC. This movie finally highlights the comedy that has always been implicit in his work. In The Music Lovers and The Devils, Russell’s jokes—about Tchaikovsky’s suicide attempt or the public exorcisms in Loudun—seem disorienting and abrasive because of the essentially serious approach, but the jokes indicate Russell’s interest in playing with multiple perspectives on his subjects. In the films he has made since Savage Messiah, comedy and satire have become even more dominant, though the results have been uneven.

Mahler, made on a low budget in 1973 and released in only a few cities in America, is conceived almost like a burlesque tour of some high points of the composer’s life. The tone is set in an early scene, when Mahler peers out of a train window and sees a fussy man who looks like Dirk Bogarde throwing shy, seductive glances at a boy in a sailor suit. This parody of Visconti’s Death in Venice (which used Mahler’s music in interpreting Thomas Mann’s novella) is multi-leveled and startlingly funny. Mahler chuckles knowingly, almost as if he has a presentiment of all the foolish abuses of his art and life; he manages to have the last laugh. Other anachronistic comic touches illustrate Russell’s irreverence: Mahler’s conversion to Catholicism is staged like a silent movie parody of a Wagner opera, with a few echoes of 8½; in one of the family scenes, Mahler’s brother does an impersonation of Harpo Marx.

The Devils

In Mahler, Russell reduces plot to a minimum and develops an unorthodox surrealist style. As Mahler and Alma travel across Austria by train, the journey is interrupted by memories and fantasies-out of chronological order-touching many of the important events in his life. Alma’s lover is also on the train, and at one point Mahler gives her an ultimatum: she must choose between them by the time the train reaches Vienna. This contrived melodrama is a feeble attempt to give the movie some suspense, and Russell cannot conceal his own boredom with the romantic triangle. The train journey is obviously nothing more than a string on which to hang a collection of interesting beads.

In program notes that Russell prepared for the movie, he claims that Mahler has the form of a musical rondo, with variations on the themes of love and death juxtaposed throughout. But this sounds like an after-the-fact rationale for a series of unrelated scenes and set pieces. Mahler does not have the dramatic or thematic unity of The Music Lovers; in this film Russell flings out ideas indiscriminately. For example, the sequence dealing with the death of Mahler’s daughter following on his composition of “Songs on the Deaths of Children”—raises interesting questions about the artist’s monomania, and the way in which life imitates art; but these ideas are not developed in the rest of the film. Russell himself admits, “My film is simply about some of the things I feel when I think of Mahler’s life and listen to his music.” Even this is not quite true; the sequence dealing with Mahler’s childhood resembles an Isaac Babel story that Russell was at one time planning to film for the BBC. Obviously the film is a grab bag; it doesn’t all hang together, and one responds simply to the individual sequences, which are almost like the production numbers in a musical.

The quality of these individual segments ranges from brilliant to embarrassing. The episode in which Mahler and his sister waltz before the mad composer Hugo Wolfe, who fancies himself the Emperor Franz Joseph, is an undergraduate’s bright idea staged for a cheesy student film. The childhood scenes are more painfully misconceived. The family’s Jewish mannerisms are so uncomfortably exaggerated that the scenes might have been staged by the anti-Semitic Cosima Wagner. Russell obviously meant to attack the family as mercenary philistines who simply happened to be Jews, but he miscalculated. Later Russell clarifies his point of view when he criticizes Mahler for giving up his Judaism in order to advance his career. The conversion fantasy is staged rather clumsily, but when Cosima begins to sing an anti-Semitic anthem set to Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” while Mahler gorges himself on pork and milk, the film reaches a liberating peak of blasphemous comedy.

This outrageousness is one of Mahler’s virtues. Yet there are also some lovely quiet moments in the film, particularly in the scenes with Mahler’s wife and children. The depiction of Mahler’s relationship with Alma is the major strength of the movie, and some of their scenes together have dramatic tension as well as emotional depth. Russell is on to a great subject here: the uneasy marriage of two talented, creative individuals, and the stifling of the lesser by the greater talent. One thinks of the relationship of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, but Alma has more resources that enable her to survive.

Mahler

An early flashback showing Alma and Mahler shortly after their marriage is a tender comic idyll. As he works in his study on the lake, Alma goes out to still the sounds of the surrounding countryside; she stops the church bells from ringing, removes the bells from the cows in the pasture, and silences an orchestra and a group of folk dancers in an open air beer garden. At the climax of the sequence, Russell intercuts Mahler conducting an imaginary orchestra as he whirls around his study with Alma conducting the now-silent dancers in the beer garden. Although this sequence is rousingly comic, we feel the poignancy of Alma’s desire to participate in her husband’s creative work in any possible way. Later, in a more profoundly melancholy scene, Mahler discourages Alma from continuing with her own musical composition; deeply hurt, she places her rejected song in a small box-shaped like a toy coffin-and buries it in the garden. The overripe romanticism of this scene (accompanied by the music from Tristan and Isolde) is partly ironic, but the images of Alma, forlorn yet dignified, walking through the darkened garden, are very moving, almost elegiac. Only an artist of remarkable sensitivity could bring off a potentially ludicrous moment like this without any condescension.

Unfortunately, the relationship of Mahler and Alma, which could have made a film in itself, is only one element in this elaborate potpourri, and Russell gets distracted by other subjects just when we are most intrigued. As a result, when Mahler and Alma are finally reconciled at the end of their journey, to the lush strains of his sixth symphony, the scene is delicately handled but fundamentally unconvincing. The tensions between them seem too strong to be so conveniently resolved. Nevertheless, Georgina Hale gives an electric performance as Alma. She is touchingly vulnerable in all the flashback sequences, while in the scenes on the train she presents a completely different side of Alma’s character-a supremely bitter, savagely sarcastic shrew. Alma’s imperious, ice-cold facade is the mask she has chiseled to conceal her frustration and disappointment over the stifling of her creative potential. The tension is palpable: we can feel the anger and pain seething beneath her sardonic exterior.

This may be the place to say something about Russell’s unorthodox heroines. Even Pauline Kael, a critic hostile to Russell’s films, recognizes that the director’s ambivalent attitude toward strong, hard-edged women created the dynamics for the memorable female performances in his films: Glenda Jackson in Women in Love and The Music Lovers, Vanessa Redgrave in The Devils, Dorothy Tutin in Savage Messiah, and Georgina Hale in Mahler. Ken Russell does not have the “correct” liberated view of women, and that is probably why feminists do not know what to make of him.

In Savage Messiah, for example, Russell ruthlessly mocks the aristocratic suffragette, “Gosh” Smith-Boyle, exposing her as a dilettante and a radical-chic hypocrite who turns into a belligerent jingoist as soon as the First World War begins. Russell contrasts her to Sophie Brzeska, a more extraordinary woman who refuses to ally herself with any of the fashionable political and artistic movements of her day. Sophie, magnificently played by Dorothy Tutin, is truly unconventional in a way that doctrinaire feminists would not begin to understand. Spinsterish, sexually repressed, embittered by her suffering, shrewdly observant, more than a little demented, unselfish in her devotion to Gaudier but unwilling to sacrifice her identity to his, Sophie is one of the most vivid, maddening women characters ever created. Russell’s acerbic, mysterious heroines are not perfect models of revolutionary activity, but they have remarkable strength; and if Russell regards them with a combination of fascination and suspicion, that ambivalence at least represents an honest response to shifting sexual attitudes. Russell confronts powerful, independent women without the aid of a modish ideology.

Mahler

In Mahler, Georgina Hale, alternately poisonous and passionate, joins Russell’s company of brilliant actresses. One wishes the film gave her more opportunity to develop her character. Still, for all of its flaws, Mahler is an inventive and riveting personal film, and it looks even better when compared to Russell’s subsequent film, Tommy. In this musical vaudeville, inspired by the Who’s inane rock opera, Russell delivers the kind of movie-to-get-stoned-by that teenagers obviously craved. The amusing thing is that the critics were equally enchanted, for Tommy validates the charges of sensationalism that were I think unfairly leveled against The Music Lovers and The Devils; this time most of the scenes have no purpose beyond shock and titillation.

In Tommy, Russell has turned into exactly what his detractors always said he was: a vulgar Barnum who sacrifices everything to flash and gimmickry. The images have the same sledgehammer crudeness as the noisy, toneless rock songs.

Tommy is inventive, but it is also exhausting, because it is so totally limited to scenes of horror and vulgarity. The feeling that comes through most strongly is one that was probably not intended—Ken Russell’s feeling of revulsion from the modern world. Tommy at least helps to explain why Russell is ordinarily drawn to period films. He obviously cannot abide the contemporary world; he is a 19th-century romantic living out of his time. This popular rock musical is a grating collage of harsh, grotesque, ugly images of war, violence, urban rot, middle-class materialism, advertising, and commercial exploitation. Russell’s films have usually contained a juxtaposition of savage and lyrical images, but Tommy is all on one shrieking note of nausea and hysteria; the persistent zoom shots are symptomatic of the frenzy. Even the images of nature are antiseptic and cliché-ridden. One field of yellow flowers is blemished by unearthly technicians in white suits and gas masks spraying insecticide. There is no exit from this urban hell—a world of sterile suburban homes, auto graveyards, regimented tourist camps, and seedy strip parlors. Ann-Margret and Oliver Reed are the perfect heroes of this gaudy plastic-and-neon universe; Russell uses them for their coarseness and their lewdness.

The fact that all of the ugliness is deliberate doesn’t make it any more enjoyable. This film does not even have the emotional impact of The Devils, a more honest nightmare film. The horrors in Tommy are sanitized, PG-rated. Technically the film is admittedly impressive; the story is developed without a word of dialogue, and the fusion of music and images is often exciting. There is wit and imagination in several of the scenes, particularly in Russell’s definitive mockery of TV advertising: the baked beans, chocolate, and soap suds being advertised on television flood right out of the tube into Ann-Margret’s posh white bedroom, and she reaches orgasm as she wallows in the muck. Since Russell himself once made TV commercials for detergent, chocolate, and baked beans, this is a scene he must have been waiting to use for a long time; he brings off a tart obscene joke on the obsessions of the consumer society.

Other set pieces—Elton John’s “Pinball Wizard” number, or the Marilyn Monroe church service—are almost as clever, but they go on much too long, as if Russell were congratulating himself on his brilliance. There is no discipline in this film, and even in technical terms, it has some surprising lapses. The psychedelic fantasy effects—miniature airplanes turning into cemetery crosses—are unimaginative; the use of rear projection is clumsy and amateurish; the zoom shots that Russell overused in Mahler are even more prevalent here; the editing often has the aggressive slickness of TV commercials. The extreme unevenness of the film’s technical achievement is troubling, because it indicates a contempt for the audience; Russell assumes that the kids watching the movie will be so numb that they won’t notice the difference between the original and the tacky effects.

Tommy

Lisztomania continues in the flamboyant circus style of Tommy. But this 19th-century comic opera (complete with rock songs adapted from Liszt’s and Wagner’s music by Rick Wakeman) is not so relentlessly ugly, and Russell’s satire has a lighter, more insolent tone, with a bit of the Goon Show flavor. One may still have reservations about the content of the film, and about the messy, haphazard structure, but this time there are no possible technical reservations. The film is sumptuously photographed (by Peter Suschitzky) and imaginatively designed (by Philip Harrison and Shirley Russell).

In this case, Russell has an underlying conception and a unifying style—a pop-art, comic-strip style, built on parodies of old movie genres. The opening, in which Liszt fights a duel with Marie d’Agoult’s effete, villainous husband, is a musical version of a Stewart Granger swashbuckler; when Liszt and Marie are locked in a piano and placed on the railroad tracks, the parody turns into a wacky variation on The Perils of Pauline. Later the movie plays with the horror genre, with pieces of Dracula and Frankenstein done in the style of Superman comics. There is also a Chaplin parody; and the ending, a sci-fi spoof set in heaven, is a cross between the heavenly fantasies of the Forties (Here Comes Mr. Jordan, Heaven Can Wait) and a Flash Gordon Serial.

Despite all these stylistic flourishes, Lisztomania has something on its mind; the collage of wild comic images builds to a climax of unexpected intensity. This is a much more adventurous, imaginative film than Tommy, but the critics who loved Tommy are howling in outrage at Russell’s venomous treatment of Liszt and Wagner. The comic-book style is used to attack the crass commercialism of both composers, their obeisance to the popular culture of their time; according to Russell, their lives played like a bad Hollywood movie. As is usually the case in Russell’s biographical films, most of the episodes have their basis in fact, but Russell bends facts when he needs to, takes liberties with chronology, and rewrites history for his own subversive purposes. The jokes and anachronisms—like the Giotto-type paintings of contemporary rock stars that line the walls of Princess Carolyn’s palace—multiply until it isn’t always clear what is being satirized.

Major events in Liszt’s life are tossed off in a line of expository dialogue, and the narrative is so fragmented that viewers who come to the movie without any knowledge of 19th-century musical history will have trouble following much of the action. Russell is undeniably cavalier and irresponsible in his approach to history, but then the film never pretends to be realistic reconstruction. Surely an artist is entitled to his own perverse revaluation of history, at least when his interpretation of the past is as provocative and original as in Lisztomania.

Lisztomania

On the subject of Liszt Russell is ambivalent. The emphasis on Liszt’s groupies, his Warhol-like decadent parties, and his garish, luxurious surroundings seems designed to portray him as a purely commercial creature, a slave to fashion and to the marketplace. In a brilliant scene staged like a rock concert, hundreds of 19th-century girls shriek and swoon during Liszt’s recital, grab at his clothing, and interrupt his serious music by screaming for him to play “Chopsticks.” He cheerfully gives the gallery what it wants. “We’re all in show business,” he tells Wagner. In another outrageous scene, several of Liszt’s mistresses (including Lola Montez and George Sand) take a ride on his 10-foot penis. In truth Liszt was a hugely successful popular pianist, a flamboyant showman, and something more than an ordinary cocksman; there is definitely a case to be made for him as a progenitor of today’s pop stars—even though the case is wildly overstated in Lisztomania.

Yet Russell also suggests that Liszt is an artist of genuine talent whose music will survive the vulgarity of his life. Unfortunately, with most of Liszt’s music turned into electronic rock, it is hard to judge his achievement from this movie. In one ambiguous sequence Liszt remembers his life of poverty when he first ran off to Switzerland with Marie. The sequence is staged like a parody of The Gold Rush, with Liszt in a Chaplin-esque mustache and a derby, composing “Dream of Love” in their quaint little cottage, while Marie throws kisses and sews a sampler with a giant red heart. The parody is done with wit and affection, but the point of view is not entirely clear. Is Liszt so hopelessly addicted to pop culture that he can only imagine artistic integrity in the sentimental terms of hearts-and-flowers melodrama? Or does the parallel to Chaplin imply that he was once an innocent folk artist? Either way you interpret it, the scene presents Liszt as a clown.

Russell’s treatment of Liszt is satiric but not really vicious. The treatment of Wagner is something else again. Russell seems to have made this film mainly to have a chance to get at Wagner (who was in reality Liszt’s son-in-law). Wagner dominates the second half of the film, and Paul Nicholas, who played cousin Kevin in Tommy, once again wipes Roger Daltrey off the screen; he is a natural screen actor, with a sly, cocky smile.

Wagner first appears as a boy in a sailor suit trying to peddle one of his compositions to Liszt. Later he returns as a vampire, who sinks his teeth into Liszt, and composes a tune on the piano while he sucks Liszt’s blood. Later still, after Liszt’s daughter Cosima has gone off to live with Wagner, Liszt arrives in a German village and asks for directions to Wagner’s castle; the horrified reactions of the townspeople recall similar scenes set in Transylvania. During an electrical storm that night, Liszt peers into the window of Wagner’s castle and sees naked orgies around the fire, ruled by a laughing, sadistic giant, an apparition from pagan mythology. Wagner appears in a Superman outfit, and surrounded by a group of blond youth, he sings a hymn to the “flowering youth of Germany” and the “Aryan superman.” Then he takes Liszt into his laboratory; on the operating table his own Frankenstein monster—a retarded Siegfried—crackles to life and sits up to do his master’s bidding. As if that weren’t enough, Liszt also has a vision of Wagner-Dracula rising from grave: the doors to Wagner’s tomb open, and the dead composer, now made up to look like a cross between the Frankenstein monster and Adolf Hitler, emerges. Followed by his youthful disciples, he enters the village and, brandishing an electric guitar which doubles as a machine gun, he mows down all the Jews.

Lisztomania

There are shards of truth in this bizarre fantasy. Musical scholars agree that Wagner borrowed and reworked some of Liszt’s musical themes in his own compositions, and he was certainly a rabid anti-Semite whose revival of pagan German myths in the Ring cycle was part of the foundation on which Hitler’s Reich was built. In The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William L. Shirer comments that Wagner’s operas “inspired the myths of modern Germany . . . which Hitler and the Nazis, with some justification, took over as their own.” Hitler himself said, “Whoever wants to understand National Socialist Germany must know Wagner.” Nevertheless, Russell’s theory of a neat causal relationship between Wagner and Hitler, a theory that ignores all the other complex factors that contributed to the rise of Nazism, is a grotesque oversimplification of history.

But it is not really fair to ask a non-documentary film to serve the same function as a careful piece of historical scholarship. Through distortion and exaggeration an artist can provide a flash of insight that might well be obscured by a more dispassionate historical theory. Russell’s vision is like a half-mad nightmare with a core of truth that cannot be discounted. He refuses to absolve the artist of responsibility for social evils, and this is the heresy that music lovers cannot tolerate. Whatever one’s reservations about Russell’s peculiar approach to German history, the climactic scenes of Lisztomania are among the best that he has ever done—blasphemous, audaciously witty, harrowing, and exhilarating.

The sense of horror and outrage in this section of the film does not come from Russell’s feeling about Hitler. His concern about the abuses of art gives the film its passion. Russell wants us to see the connections between Liszt and Wagner—a not just the family connection or the musical influence of one on the other, but the influence of Liszt’s flamboyant commercialism on Wagner’s megalomania. The cult of the superstar leads to the more sinister cult of the superman. Liszt’s screaming fans are the same girls who stand respectfully in front of Wagner’s tomb. Russell’s point is not simply that hysterical teenagers are incipient fascists. What he is really saying in Lisztomania is that once the artist surrenders to the rule of marketplace, he has violated the natural order of the universe and released demons that cannot be controlled.

The Nazi scenes are not meant to be taken literally; they express Russell’s worst fears of what can happen when art is perverted by show business and political fanaticism. The paranoia in this view of the artist’s responsibility is bizarre, but there is something irresistibly romantic in Russell’s concern for the artist’s integrity. In a world where every thing has been debased and devalued, Russell still envisions art as the central creative act that brings order to a chaotic universe. The fact that most of his films examine the artist’s betrayal of his vocation cannot obscure Russell’s belief in the moral importance of art. His exalted view of art seems slightly insane and rather breathtaking.

The major problem with Lisztomania is formal. The pop-art style is effective for dealing with Liszt’s vulgar showmanship, but it limits the scope of the film. Elements of Liszt’s life that do not fit the cartoon pageant—his long-term relationship with the Russian Princess Carolyn, or his decision to enter the priesthood—must be rushed over. Toward the end of the film, Russell seems to want to portray Liszt more sympathetically, but his style is not flexible enough to reflect this shift in attitude, and Roger Daltrey is too inexperienced and vacant an actor to create a character with any complexity.

Lisztomania

The ending—a fantasy in which Liszt and the women in his life are in heaven looking down at the results of the Nazi holocaust—is cleverly conceived but specious. Liszt seems to believe that his and Wagner’s music will be remembered long after the evil consequences of the music have been forgotten. His discarded mistress Marie announces, “The best of us lives on in the music, for everyone to share.” Liszt and the women enter a rocket ship shaped like an organ and return to earth to destroy Wagner-Hitler and put out the fires in Berlin. As he flies away from the battlefield, Liszt sings “Peace at last” before returning to heaven. As in Tommy, Russell tries to end on a note of Christian redemption; but although the conclusion of Lisztomania is much wittier than the ending of Tommy, it cannot match the urgency of the nightmare images in Wagner’s castle.

Perhaps this ending would have been more effective if the rest of the film had more mysterious romantic images to reflect Liszt’s idealism. Russell’s earlier films have a broader range of moods and emotions. The Music Lovers is divided between scenes of horror and scenes of decadent but hypnotic romanticism; that tension gives the film its extraordinary impact. Even The Devils, more frenzied and grotesque, offers some contrast to the scenes of death and torture in the tender scenes of Grandier ‘s marriage to Madeleine. The loud, garish style of Tommy and Lisztomania is unrelieved by quieter moments. At its best Lisztomania is exceptionally powerful, but there are no shadings in the film, and that’s why some of the spectacular set pieces grow tiresome.

Both Tommy and Lisztomania are inventive but singularly unmoving; almost the only emotion they inspire is horror. In Savage Messiah Russell’s affection for the characters is more important than any of his bravura effects. Even Mahler, which is closer to the style of a cartoon, has passionate feeling in some of the scenes between Mahler and Alma. The circus format of Tommy and Lisztomania is partly a function of the subject matter of these two films, but one cannot help feeling a measure of concern about Russell’s increasing indifference to recognizable human emotions.

After Savage Messiah and Mahler, Russell was regarded by the industry as a dangerously eccentric director, and he desperately needed a hit. Therefore the garish carnival style of Tommy and Lisztomania can possible be explained as commercial calculation; the casting of pop stars in both movies tends to support the supposition that these movies were made with an eye on the box office. Of course that makes Russell’s attack on commercialism in Lisztomania doubly ironic. Is Russell aware of the irony? He once offered a distinction between commercialism and vulgarity: vulgarity, he told John Baxter, is “an exuberant over-the-top larger-than-life slightly bad taste red-blooded thing.” Undoubtedly he would define his own gaudy flourishes as vulgar rather than commercially oriented, but the distinction tends to blur, An artist who begins with a healthy desire to violate fastidious standards of good taste and shock the philistines may before long be playing to the gallery, going for broad, splashy effects that delight his less demanding fans.

The Music Lovers

Another reason for the disjointed, musical-comedy form of these last three films may be that Russell wrote the scripts himself, and he has a very poor sense of structure. The two films that I consider his most fully achieved—The Music Lovers and Savage Messiah—both had screenplays written by other people (Melvyn Bragg and Christopher Logue, respectively). Obviously Russell had a great deal to do with the writing of both those movies. I am sure that he directed the writers as closely as he directed the actors and technicians, and he clearly interpreted both scripts in his own distinctive fashion. But the scripts provided a dramatic momentum that his recent films have lacked.

Despite all the talk about personal filmmaking, there are very few filmmakers in the world who consistently write their own scripts without any assistance. Even the European directors whose work is uniquely personal—Fellini, Antonioni, Bunuel, Truffaut—almost always work with writers. Their relationship with their writers is very different from the Hollywood system where a director is assigned to a completed screenplay; in Europe the finished film represents one man’s vision, and the screenwriters subordinate themselves to the director. But those directors know that they need writers for construction and dialogue, and maybe to check some of their wilder impulses. Ken Russell’s recent films could use more discipline, and they could also use the talents of someone who has a better ear for dialogue; Russell writes arch, highly rhetorical dialogue that is occasionally witty but more often turgid or coy. To put it more simply, Russell needs a writer to question his ideas, someone to provide a sense of balance and proportion. I find it encouraging that on his current project, Valentino, Russell is working with Mardik Martin, the talented co-author of Mean Streets.

It would be foolish to make any confident predictions about Russell’s future. He has changed style before; he followed the elegiac Song of Summer with the flamboyant, abrasive Dance of the Seven Veils, and he went from the apocalyptic horror of The Devils to the campy comedy of The Boy Friend and the mellow romanticism of Savage Messiah. Mixed responses to Russell’s films are understandable. His startling visual imagination, and the profound feeling of his best work, attest to his exceptional talent. At the same time it is impossible not to feel a little queasy about Russell’s egomania, his willingness to distort and discard any historical facts that do not fit his preconceptions. But the artist’s arrogance is one of Russell’s recurring subjects; he is deeply implicated in the moral dramas he poses, and that is why his films never feel pat or complacent.

On one point there can be little disagreement Ken Russell is not one of the great humanist directors. Pauline Kael wrote of Savage Messiah: “This is ‘art’ for people who don’t want to get close to human relationships, for those who feel safer with bravura splashiness . . . What is the sum total of [Russell’s] vision but a sham superiority to simple human needs, a camp put-down of everything?” It is true that Russell’s strengths do not include warmth and compassion. Human relationships interest him, but he treats them in archetypal, almost abstract terms. Anyone who looks to his films for the kind of richly detailed characterizations found in the films of Renoir or De Sica will be disappointed. But there are other criteria for evaluating works of art. Imaginative power is as important as love of humanity. Critics often have the naive notion that humanistic film s done in a naturalistic style are the only works that deserve to be called art; they misunderstand and underestimate Russell’s dazzling baroque films.

Mahler

Russell’s work is blemished by arrogance, self-indulgence, pomposity, and sensationalism; but among filmmakers, those weaknesses are often inseparable from strengths. Artists are drawn to the film medium by a desire to give form to their most outlandish visions, and also by a lust for power; a movie director is an artist with some of the same fantasies as generals and despots. One can trace a growing arrogance and pretension in the works of Chaplin, von Sternberg, Welles, Fellini, Visconti, Kubrick, Boorman, to name just a few. Most of them have an irrepressible showman’s instinct, like Russell. Russell’s work can be characterized as a series of vulgar, self-indulgent set pieces without an organizing principle; but the same criticisms have often been directed at the later films of Welles and Fellini, and that may be one of the by-products of an original and anarchic cinematic imagination.

As a matter of fact, many of the criticisms directed at Russell’s films could also be leveled at Robert Altman’s. Pauline Kael’s most beloved and most despised directors have more in common than she would like to admit. Russell’s florid, overheated style is the opposite of Altman’s casual, throwaway style; and whereas Russell achieves his effects primarily through cinematic means, Altman works through his actors. But both directors have the same suspicion of intellectual analysis, the same single-minded arrogance, and the same faulty sense of narrative structure. Altman’s movies have been compared to parties, and Russell’s might be called more decadent and exotic parties. I am not trying to suggest that the two directors are exactly alike; but the problems in Russell’s movies are similar to the problems that confront many of the most innovative artists working in the medium.

Although the narrative tradition has broken down, filmmakers have not yet discovered anything to replace it. The most original and important artists—in fiction as well as in film—are all grappling with the question of structure. Russell’s daring but still imperfect experiments with kaleidoscopic, non-linear, operatic style are symptomatic of a formal quandary that affects all filmmakers. Russell is one of the few artists who is pushing forward, working to forge a purely visual vocabulary. His most compelling images and characters already have a place in film history.