Interview: Alexander Kluge

Alexander Kluge was born in the Prussian town of Halberstadt on February 14, 1932. Three years earlier, Al Capone had already robbed St. Valentine of some of his sentimental magic, and Kluge’s own eleventh birthday was more immediately overshadowed by the fact that, 11 days earlier, the Press Office of the Third Reich had officially acknowledged the end of “the heroic battle for Stalingrad” and declared several days of national mourning.

For Kluge, the mourning for the millions of lives wasted and scarred by National Socialism is—like the process itself—not yet over. Images of senseless destruction and mindless reconstruction are frequently intercut with the frenetic activities of his screen heroines; while his prolific “literary” output includes two documentary novels: The Battle, concerned with the Germans’ defeat at Stalingrad in 1943; and Attendance List for a Funeral (Lebenslaufe, 62), of which one story, “Anita G.,” contains the basis for Yesterday Girl).

More recently, Kluge has co-authored with SDS theoretician Oskar Negt a rather formidable tome, Public Life and Experience (Offentlichkeit und Erfahrung, 72), about the organizational structures of bourgeois and proletarian experience; and has also published a volume of his own short stories, some of them science-fiction, Learning Processes with a Deadly Outcome (73). He still practices as a lawyer, and is a Professor of Law at the University of Frankfurt. On the lighter side, he collects old Mack Sennett movies, nursery rhymes and toys, and was pseudonymously responsible for that minor Latin classic, Winnie ille Pu.

Kluge’s latest film, Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave stars his younger sister Alexandra (from Yesterday Girl) as Roswitha Bronski, an impulsive Utopian whose devotion to her own family leads her up and down a snakes-and-ladders career as abortionist, political agitator and sausage vendor. On Kluge’s own admission, the second half of the film—the section outside the Bronski home—was shaped by his sister’s ideas rather than by his original intentions. (“The director’s role is to interpret the experiences of his interpreters.”) Whatever their shared obsessions, the generation gap has evidently exposed the sister to a less cautious faith in the efficacy of localized militancy.

In Munich last July, while he was finishing his latest book for a deadline in Frankfurt and I was attempting to view all of Fassbinder’s films, Kluge and I had a fragmented, three-day conversation of which only the last two hours were taped. At the end of the recording, and again after he’d read the verbatim transcript, Kluge complained that it was all too abstract and asked me to cut down the generalizations and explicate his meaning with more concrete illustrations from the films. He himself has made some drastic excisions, and I have done my provisional best. But since he does affirm that “the real film is the one in the spectator’s mind,” I hope he won’t mind if FILM COMMENT readers create their own interview from the text that follows. The interview-film in my own head may take some years to edit.

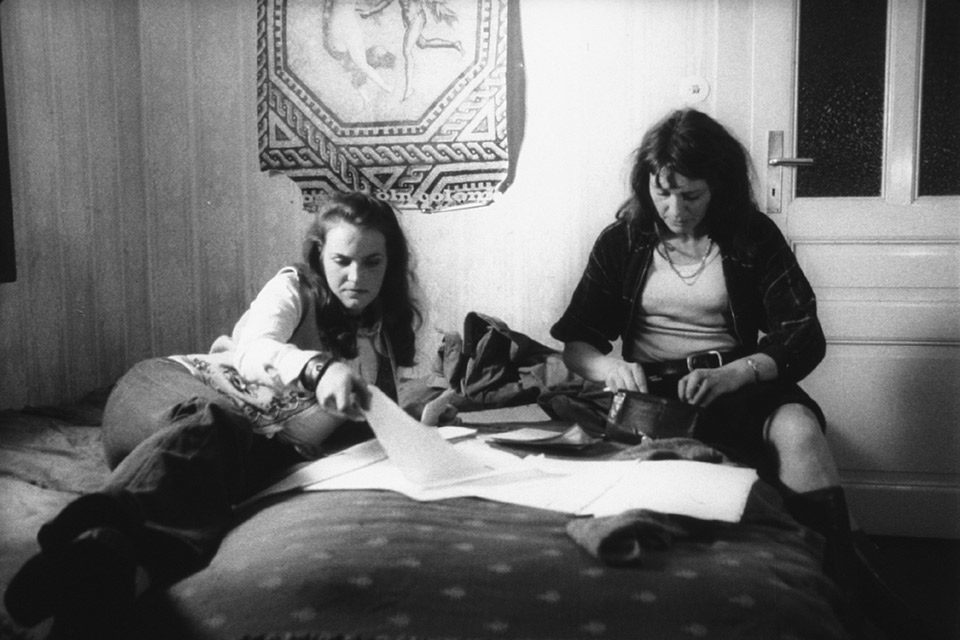

Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave

Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave is most often discussed as a possible tract for Women’s Lib or in terms of the abortion debate. Whereas it seems to me to deal with a more comprehensive theme: the fundamental incompatibility of family values and social values—the impossibility of what we might call social loyalty existing in a social structure where family loyalty is the priority. Would you like to comment on this?

If the distinction between public and private is the main element of the society that believes in property, it follows that the family is an elementary organism of this society. In the same way that the entrepreneur accumulates money, the family accumulates warmth, human relationships, for themselves. Happiness for themselves, and neglect for anyone else.

At the beginning of the film, we see a family scene, with the parents and children standing at the window. Outside, snow is falling. Inside, the warmth; outside, the cold. Auschwitz never disturbed the idyll of happy family life in the Germany of the Thirties.

The organization of the family, the private organization of getting children and trying to be happy in an organizational ruin like the family, is something that only exists in the imagination of the family’s members. And if you accept that this elementary organization is a school for ideology, you are confronted with a rather difficult situation. Women have to do with children, with making human beings—producing something no factory could do. They don’t produce cars, they don’t produce potatoes, they produce children. And that involves a principle of satisfying the needs of other human beings. A child is nourished because it needs, not because it demands. And I think that this relationship between mother and child is a rather progressive, rather hopeful relation between human beings. From one point of view. But this form of production exists only on a kind of private, Robinson Crusoe island. Jealousy or property, for example, separate it from society. So you get the contradiction that the “female experience” is both progressive and conservative. Women cannot liberate themselves on the basis of this contradiction.

The new film offers an example of this. Statistically, it’s rare that a mother, in order to get more children of her own, runs an abortion clinic. It’s more of a metaphor, a device for conveying an existing attitude. The idea of helping her children live by killing other people’s is merely a concentrated expression of the contradiction that exists in any family.

Marx always said that only the working class have a sincere motive for changing society. But they don’t have the means to do it. The proletariat is by definition a class that does not possess the means of production. Other social groups, intellectuals for instance, have more means than they need, but lack the motives.

Women produce the right things: human beings. But there’s always the conservative element, they’re defending their private mode of production. Women, like the working class, can only emancipate themselves if they use the means and the motives of all classes. You don’t achieve social change by eliminating human qualities.

But in all your talk of social change, the element in the existing models that you appear to challenge least strongly is the contradictory relationship between mother and child. You just defined it as an example of non-alienated production…

Not non-alienated. Without alienation. It’s surrounded by alienation and determined partially by alienation, but it itself is not completely alienated.

But at the very beginning of Yesterday Girl, before what might loosely be described as the film’s narrative begins, there’s an isolated quotation about the evil of separating mothers from children.

Exactly! It’s from a text by a priest in Ancient Egypt. Anita G. has just discovered it in a library, and she’s reading it, and laughing at it, and taking it seriously at the same time.

And which are you doing?

[No response.]

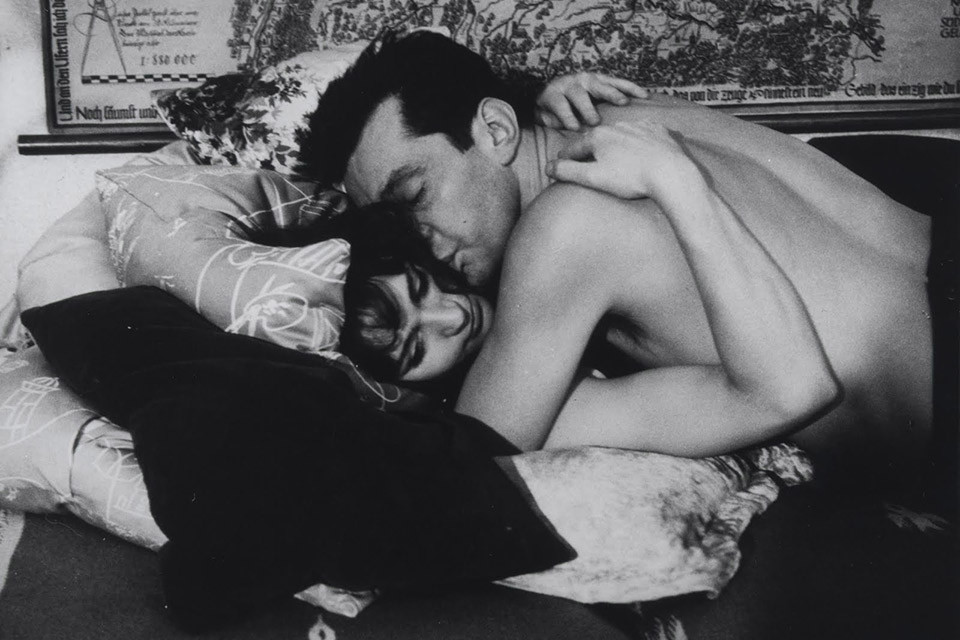

Yesterday Girl

When you talk about history, you say it’s essential to know the past in order to really exist in the present. To what extent is this true of the relationship between mother and child? Don’t the possibilities for change perhaps lie in children knowing less of their individual histories and more of their collective history?

A child doesn’t only understand what its mother says or does consciously. Her habits and gestures are far more revealing. If, for example, the mother is afraid the child will destroy one of her possessions, then the child learns quite a lot.

There’s another aspect to this. When the mother and child are alone in what we like to think of as an “action moment,” a moment of pure present tense—for instance when the child’s supposed to be going to sleep and the mother’s telling it a story—their whole past is present: the absent husband, the history of this woman and her husband, the history of this woman and her parents. They’re all present. And to some extent the child’s future is present too. The reality is what you can’t see.

Anyway, having children and educating them has nothing to do with privacy. It’s a social relation. Only it isn’t seen as one or lived as one; it’s lived in an anarchic way. It’s no longer collective and it’s not yet individual. It’s nothing, it’s just the middle of the road.

Your films are always centered on a female character who seems, in some curious way, to be immune from their general, overall irony. I also think you offer a fairly tough and basically unsympathetic treatment of the male characters; and a rather depressing view of the actual, possible relations between men and women. Is that a correct impression?

It would be pointless to say that it’s not. In a society dominated by men—a society whose mentality and institutions, from school to university to the law courts, are essentially masculine—it’s not capricious to describe some men as “character-masks.” They are. And in so far as they belong to institutions and are formed by institutions, they become more like character-masks. The security officer in the factory in Part-Time Work, for example, or the chief doctor who quarrels with Roswitha: each of them is closer to a character-mask, in my opinion, than a real being like Roswitha or Leni Peickert [of Artists Under the Big Top: Perplexed] or Anita G. [Yesterday Girl]. On the other hand, there are some men—as you may have recognized—who have some female soul in a masculine body. Doctor Bauer, the Attorney General who appears in Yesterday Girl, is a real person; even though he works in an institution, he would never try to reduce to a character-mask somebody who is not a character-mask.

You use the words “female” and “male” rather as if female meant “good” and male meant “bad.”

To some extent that’s what I believe. I’m not talking about distinctions between male and female bodies. Men can also have qualities that I’d consider female. Kleist said of the arts that music is female; in Britain you have ships, and you think of them as female.

The male characters in your films are to some extent invisible, they don’t have a very strong reality.

Yes.

I find it curious, or at least worth talking about, that in your films the relations between men and women are usually extremely functional—very hygienic and unsatisfactory. They hardly suggest the possibility of a harmonious co-existence between male and female…

I would never try to construct a racism on the division of male and female. But I do think that it’s always the suppressed element in society that has to be described: the dominant element describes itself; there’s no need to add to it in the cinema. It’s much better to describe the sub-dominant element, the suppressed element. These are lives that society does not intend to use in the good sense. It takes them, it takes life, because it can’t get rid of it, because it’s necessary for work and for making values. But this society has nothing to do with living. Whereas the cinema has a lot to do with living, and with the observation of living experience.

Yesterday Girl

But I was asking more specifically about the lack of tenderness between men and women. The only instance of tenderness I could find was that between Leni Peickert and her father; and the tenderness between them was made possible largely by the fact that the father was already dead.

Tenderness doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with actual presence. Presence, an actual situation, mostly destroys it. But I believe there’s a lot of tenderness in my films as a whole: Anita’s relation to her shoes, when she’s cleaning shoes; or Roswitha’s feeling for her husband as she’s nearing Portugal to investigate rumors about the new factory. When they’re together, they have nothing to say to each other; when they’re apart, they have to say something. And I don’t mean that as a paradox. There are situations in which the destructive element in our relationships is less dominant: and those situations most frequently involve absence.

There’s a moment in the last film that I find very beautiful, and that also seems to resume the relationship between the couple: Roswitha buys books because she wants Franz to see that she’s become a serious person; but before she’s read them, he insists on telling her what she will find inside them.

It’s also a moment when they don’t speak to each other. They’re concerned with each other, but they can’t express it.

Both your films and your conversation suggest that, in terms of social change and reorganization, the family is the structure from which we should attempt to move away. It’s therefore curious that you should have worked quite consistently and very closely with your own family. You made a short film, Frau Blackburn wird gefilmt, about your grandmother; and your sister has been the leading actress in at least two of your feature films.

You don’t get rid of something by not caring for it.

But as you say in Artists Under the Big Top, “merely to care is not enough.”

It isn’t enough, but without caring, you couldn’t even work on it.

But the film about your grandmother is hardly an attempt to change her. It’s more like a monument to her, and to the changes she’s experienced in her lifetime.

That’s partly because she was 100 years old at the time, and there was no reason to change her for her 101st year. It’s different if I’m dealing with our generation. You have to understand that I believe in a different type of change. I don’t believe you really achieve change by decisions, or by killing the past, or by killing people. That’s not the way to change anything. Robespierre and Saint-Just followed the typical, European mentality—and all they could do was cut off heads. But they didn’t change anything. Society changed in spite of them, in spite of the decapitations. It’s trying to establish virtue on earth that gives capitalism, or Napoleon, the chance to develop. A better way to change things is to accept the past and to complete it. The only way to change history is to regain it.

Artists Under the Big Top

And how does that work out for you privately? In terms of your own family? Or is that another abstract question?

It’s not at all abstract. I love some members of my family: for instance, my sister, my mother, my father, my grandfather. At the same time I’m quite sure that society couldn’t live, that I myself couldn’t live, in the way my mother, my father, my grandfather lived; not even the way my sister believes in. And I think that’s not a personal problem of mine. During anyone’s lifetime, existing lifestyles and programs for living become meaningless. So that, whether we want to or not, change and the observation of complex situations are something we all learn. But the history of our society’s contradictions is teaching a new sensuality that is less interested in linear progression, or in “good” and “bad” than in recognizing the complex and the contradictory as the dialectic of things.

I don’t believe in dialectics as a mode or abstract thought. I believe in a dialectic we can feel with our fingertips.

You use the phrase “materialist aesthetics,” and you also talk about your films as attempts to describe something that doesn’t exist. And in order to make this description, you have at your disposal the materialist aesthetics…

That’s not a contradiction. Materialist aesthetics means, in the first place, a way of organizing collective social experience. This collective social experience exists with films or without them. It has existed for about 300,000 years, and been “actualized” for only about 300 of them, because social development grew faster. The invention of film, of the cinema, is only an industrial answer to the film that has its basis in the film in people’s minds. The stream of associations that is the basis of thinking and feeling—logic, or geometry, or whatever are not the bases—this stream of associations has all the qualities of cinema. And everything you can do with your mind and your senses you can do in the cinema.

You could understand film history as merely the collected ideas of different auteurs or entrepreneurs. But it’s not the basis, it’s an abstraction, it’s the median. Whereas the real mass medium is the people themselves, not the derivatives like cinema or television. And if you have a conception of film that means that it’s the spectators who produce their films, and not the authors who produce the screenplay for the spectators, then you have a materialist theory.

For example, there’s a street in Frankfurt where I can observe a very high concentration of porno cinemas. And the immigrant workers who watch the very bad and anti-erotic pornography there see quite different films from the ones I see. Because they produce them as tender, erotic films, even though the films are hostile to eroticism. They change the films through the productions of their own minds.

Another example: Dovzhenko made films in which the spectators could contribute their own experience; and the films are enriched by the spectators’ experience. And we call this position materialist because it thinks from the bottom up, from the spectator and the cinema in his mind, to the the cinema on the screen. The cinema on the screen is only a way of organizing experience that already exists before the film is made. The question of whether or not you consider the film as “good” depends on whether you believe in art, with all the consequences of the disoriented artists under the big top—of whether you’re concerned with the development of minds. And minds are rather flexible, not very fragile, and they always try to find exits.

The obvious question is how you reconcile your theory with the inescapable fact that as a filmmaker you’re working as an individual. You may be organizing existing material, you may be making a collage; but you are also making a selection.

Of course “I know that I know nothing.” Brecht’s Socrates said that. I think one can only be cautious, even passive to some extent. If the film is active, the spectator becomes passive; that’s a very general rule. Hollywood films try to persuade the audience to give up their own experience and follow the more organized experience of the film. In my opinion, the opposite is right.

You asked another question. Why a film, because of its montage, etc., is only a selective reality…

That wasn’t quite the question I asked, but go ahead and answer it.

Look, there are two principles that I always control, and sometimes that’s nearly all I do control. One, the situation; two, the actor’s state of mind. The situation has to do with the acting; the acting has to do with the social situation it concerns . . . and so on, ad infinitum. And I can study and even control their relative proportions; and the proportions are organized from the principle of authenticity. That’s the ideal. And we do quite a lot of things that are not very practical, like using direct sound; and we have to have huge cameras, which are not very practical, in order to get this authenticity; and we lose quite a lot of material. For instance, we shoot 20 or 30 times as much film as we need for the edited version in order to achieve this authenticity. These are the elements, the original material; and then when we make the film, we cut it and this changes. Because the cut film is not authentic. And another of the director’s responsibilities is to see that different proportions together give a result that fits as a whole with the authentic state of the society or part of society that he’s describing.

Yesterday Girl

You’re using the raw materials of actual experience to suggest something that doesn’t exist, and that maybe cannot exist, or cannot exist yet. Is that something you think consistently, or just something you tossed off?

Whether it exists or doesn’t exist is none too certain. What you notice as realistic, given the way our sense have been educated, is not necessarily or certainly real. The potential and the historical roots and the detours of possibilities also belong to reality. The realistic result, the actual result, is only an abstraction that has murdered all other possibilities for the moment. But these possibilities will recur. Which is why I don’t believe too much in documentary realism: because it doesn’t describe reality. The most ideological illusion of all would be to believe that documentary realism is realism.

On the other hand—to some extent because it’s the reality of our minds, because to some extent it’s the reality of the best parts, and imagination is more repressed than documents or common sense—I think that the testimony of fiction is better than the testimony of nonfiction. Fiction is mimetic, imitative, because it’s hiding behind nonfiction; and I think these are two sides of the same thing. Which is why I always try to mix these two things—not simply for the sake of mixing them, but rather to create in any film the maximum possible tensions between fiction and nonfiction. Roswitha, for example, meets a real Minister from the State Government, she follows the State Government’s study of the social situation; and there’s a strong element of fiction in the enterprises of these real ministers. It’s really fiction. It has nothing to do with reality: they’re not at all interested in the social situation, they’re performing a play. And the play only becomes real because I add a fictional character to it. By adding fiction, I turn the fictional character of the nonfiction into nonfiction!

The theme of forgetting and remembering runs constantly throughout your films. In Yesterday Girl, Anita G. is encumbered with a double past that society is encouraging her to forget: at the beginning of the film she’s being told by a judge to forget her wartime experiences because they’re not “relevant” to her present situation; later, when she’s supposedly being rehabilitated for society, she’s told by one of the prison counsellors that she’ll soon be out and able to forget all about it. It seems obvious to me that, through your films, you’re attacking not just the politics of oblivion, but also the moral notion of absolution that this frequently implies.

Experience is always a question of a specific situation. In this concrete situation, there is always future, past, and actual present: it’s the same. In a mass medium like the cinema, or in art, it seems as if you have a choice. A great deal of art—Proust, for example, or any of the 19th-century classic novels—attempts to counter the dominance of the present, to invent a second reality to serve as viceroy to the forgotten or demolished past. That’s one choice. The other choice, which is made by television and by the press, is the actuality principle. It’s also the choice made by the film camera, which can only photograph something that’s present. And I think it’s a false choice, because in a concrete situation, such as we actually live in, you can never make that separation: you can never give up the past, you can never exclude the future. Which is why I prefer the past or the future to the present. Whether I’m making a science-fiction film or historical film, using inserts, making a documentary or mixing fiction and nonfiction, it’s exactly the same. The three parts that exist in our minds and in our experience are always present. When Freud describes the way a person thinks and feels, he always talks about free association as the elementary unit. Grammar, for instance, is one of mankind’s most interesting illusions. It’s a sort of repression of an experience, like logic, or like rationalism. You have to understand that I’m never against grammar, rationality, or logic; it’s just that they’re only abstractions. In any concrete situation, these abstractions must be reduced to the concrete situation. And that’s the province of film. This sort of mass medium film has its basis in people’s minds and experience over several thousand years.

For instance, the title Abschied von Gestern [the German-language title for Yesterday Girl] provokes a contradiction. Because you never can say goodbye to yesterday. If you try to, you get as far as tomorrow only to discover yesterday all over again. The whole film is a contradiction of this title… What part of your question shall I answer now?

Perhaps you could go through the films, and give a few concrete examples of these abstract principles.

Anita G. was born in a Jewish family that left in the Thirties, and she got her socialization with the experience that there is a form of society that will suppress and kill your family, and eventually yourself. After 1945, this family is hon¬ored in Leipzig, in the then Russian zone, later the DDR; and someone who was persecuted by the fascists now behaves like a capitalist and attempts to reacquire what the family thinks makes for happiness. So then Anita’s parents—and her story is based on an authentic case history—are persecuted as capitalists, and she goes to the Federal Republic, hoping to find out about her fatherland. But this Federal Republic in no way recognizes the situation in which it actually is. The Federal Republic would certainly not exist without the DDR, nor without the Third Reich. And I think someone who has concrete experience of our society’s history and who comes into an ahistorical society that is pressured not to notice its past will have conflicts. And these conflicts can’t be observed on the level of pure commonsense, or on the level on which institutions function. That’s why the people around Anita G. can’t understand why she behaves like a criminal, or why she tries to become happy but doesn’t succeed; or why she gives up opportunities and tries to find chances where none exist.

Another linguistic difficulty is that we have an expression for “what it is necessary to do.” Our education and our philosophy and our language already mirror false structures. We have expressions for consciousness and for the senses, as if senses were to do with instinct, or were something lower than consciousness. The senses are a substance of consciousness, nothing else, and you can’t have consciousness without its substance. And you can’t have your senses without organizing them. And so you get left-wing sects who want to achieve pure consciousness; and you get National Socialists who want to achieve “pure instinct,” who want to make power and life without consciousness, to think not with the whole brain but with the middle, atavistic part of it. In our sort of society, you’re taught that it’s always possible to divide everything—to use yourself and your capacities partially. But you have virtually no expression for using them all, not in an instrumental way.

I think cinema has one possibility other arts don’t have. Because it’s rather trivial and derives from the fairground. It has more to do with Punch and Judy than with a serious art. And it hasn’t been developed from the viewpoint of a small, educated society; it’s made for the plebeian people, for the proletarian component.

Do you think that’s particularly true of the films you make?

Of course not. But because I like the chance film offers, I try to reinvent its possibilities. The difficult thing is to succeed. Because film is not produced by auteurs alone, but by the dialogue between spectators and authors. And to the extent that we fail to get into the real cinemas, the ones that have the mass loyalty of the mass audience, we have difficulties and are wrongly inclined to become too easily esoteric. There’s another difficulty. The whole culture industry is busy persuading people to divide their senses and their consciousness. Even language, the whole cultural structure—the structuralists try to study it—persuades people not to interest themselves in the elementary basis of their awareness, in their way of observing, in their sensuality. Karl Marx says that the whole of human history made the five senses and educated them; and then the sense of property developed and dominated all the other senses. So that the spectators and the authors don’t possess the senses they have.

Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave

Yes. But we keep getting into abstractions and away from the small, concrete…

It would be better if you asked a few simple questions. I can’t make such long monologues without getting abstract.

It seems to me that the idea of demolishing and rebuilding runs throughout all your films, and it’s particularly strong in the first two features. Through the films, and through your use of juxtapositions, it’s presented as a demonstrably false idea, as a method that can lead only to further chaos, confusion, and unhappiness. I think that in Part-Time Work, this idea is both more complicated and less explicit.

Oh, no. To some extent it’s always the same subject. If it’s impossible to separate past from present, it’s equally impossible for there to be a division of labor between artists and workers, or between Utopia and reality. You can’t make separate societies outside society. You can’t begin like Adam and Eve; or like the French Revolution, inventing the year Zero and getting as far as the year Five; or like the Soviet Revolution, in 1917, until the New Economic Policy in 1920. All attempts to divide a concrete social situation and to invent a new world damage the possibility of a subject/object relation. And it is rather necessary to change the mere individual relation between man and society into a collective situation. It’s necessary and it costs a great deal of work.

But establishing separate quarters in opposition to the other society—the rive gauche, for instance, or Godard’s attempted return to zero—is no solution to any social relation. And if Roswitha tries to get rid of her family problems—she thinks she can’t solve them within the family—and goes into politics and tries to solve them through politics, because that’s what other groups do, she’ll merely import her private way of acting and thinking into politics. It’s interesting, but it doesn’t provide her with any more solutions than she had at home.

Isn’t there a slight contradiction there? You’ve said that one has to try and transform individual experience into collective consciousness. Yet it seems to me that the difference between Anita G. at one extreme, Leni Peickert in the middle, and Roswitha at the furthest extreme is that the last two do attempt some form of group activity. Obviously, the circus is a rather obscure cultural ghetto…

A left-wing sect is also a cultural ghetto. So is being right-wing and conservative. According to our cultural tradition, being an artist is also a cultural ghetto. Guilty or not guilty, a judge or not a judge, it’s always a cultural ghetto. Collectiveness isn’t just a question of founding groups. It’s also a question of your single capacities, which are developed in a different historical way. Your ears are developed by society separately, differently, from your eyes. A worker’s eyes aren’t developed the same as an oculist’s or an astronomer’s. All these single capacities, the single sciences, the single, sensory basis of human beings, are developed in hot house conditions. Some are developed very fast, and some are repressed and reduced. They have a different social determination. And it’s the cooperation of these separated human capacities that makes the individual.

To be just a little more concrete, it seems to me that of all your heroines, Roswitha is the one who comes closest to trying to put her different capacities, or at least her different confusions, in the same place…

That’s true.

But at the same time, she’s probably the one you treat most ironically.

Well, we had the ’68 student movement and to some extent it showed that there are some chances of changing society. The way of thinking has become more practical. Utopia and cineastic observation are more pure and look better if you have no opportunity to become practical. The more practical any situation becomes, the more ridiculous it becomes.

Judging these things is not the aim of cinema, and it’s not my purpose in trying to make observations. But I think one should show what one notices. I notice that somebody has seen the possibility of doing practical work; and I believe it’s not impossible to go on with the work Roswitha’s doing, because it would change society after a while. It took 800 years to develop capitalism to the point of the French Revolution; and it will take quite a lot of years to prepare experience and organize a period that could make a more socialist society. It will probably take more time, more activity, and more interest than was needed to invent this capitalist society. Which is why Leni Peickert’s methods, either in television or in the circus, can lead to no end. The more she tries, the more she’s separated from the masses.

Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave

To return to the theme of demolition and of rebuilding a future society: where I find Part-Time Work more complicated, and perhaps more contradictory than the other films is that you not only have the political level, which you’ve mentioned as Roswitha’s program, and which ends up reduced really to absurdity with her selling the workers ulcer-giving sausages wrapped in tracts to promote their political and mental health; you also have the idea of demolition in a form that is both more private and more social—the act of abortion. And it seems to me that your views on the family and your ideas about individual’s freedom of choice conflict slightly with your semi-deterministic views about the historical process.

The historical process is never determined. In the same way that the sea isn’t determined; but that doesn’t mean you can’t study the tides. In the same way, the planets are not determined; but you can, as an astronomer, study their laws. In any situation you can behave wrongly or correctly. You can fit, you can have a consciousness adapted to the situation, or you can have a consciousness that has nothing to do with it. And I think these two sides, and the choices, are produced by history.

The student movement, for instance, has two aspects that are both separate and combined. On the one hand, they’re trying to begin like the French Revolution, returning to zero, destroying the museums, and so on. On the other hand, they’re much more practical than we were; they combine theory and practice in a way I don’t think anyone did before. So there’s always an optimistic side and a pessimistic side: something that fits reality and something that doesn’t fit it, both mixed together. And I believe it’s necessary to begin by observing these things. Only after that can you take sides. Without seeing anything, you can’t be partisan.

The difficult thing about taking sides is that it means a lot of reality; and having the possibility of recognizing reality sometimes damages your ability to take sides; and you have to accept this dialectic. The more practical a person’s activities are, the more faults will emerge. The less practical the activities—Anita G.’s or Leni Peickert’s, even though society may interpret them as social acts—the fewer faults. It’s because what they’re doing is not so realistic as what Roswitha’s doing that their actions looks finer. The fact that they have a line, a direction, is not realistic. It slightly isolates them on one of society’s wing-tips, and it means they don’t have so many opportunities to make mistakes. Roswitha, whose path in my opinion is closer to the right one—because it’s more effective and more practical—has more opportunities for making mistakes. The only possible way to avoid mistakes is to do nothing.

I don’t think it’s clear from the film whether you see Roswitha’s work in politics as being in contradiction with her work in the abortion clinic, or as being a similar, parallel activity. In the abortion sequences—I remember you said at your press conference that they weren’t actual abortions but that an abortionist would not have performed them differently—the clinical detail was for me a much more powerful argument against abortion than any more orthodox propaganda. Yet the film’s theme—of the conflict between family values and social goals—would suggest that abortion is an essential social choice. Do you think your film is entirely consistent on this question?

I think the same way of acting and the same directness in satisfying her own needs are involved, whether Roswitha is performing an abortion or distributing leaflets. Anyone who can perform abortions side by side with attempting a happy family life would be capable of attacking a factory in an equally direct way.

But the proportions of the camera…

Yes. In terms of the camera, it’s not the same. And there’s a reason for that. First, I don’t think abortion is a legal question or something you can stamp out by legislation. And therefore I’m in favor of abolishing Paragraph 218 of the Criminal Code. On the other hand, I think that society, and women especially, can hardly feel friendly toward abortion. I don’t think abortion is a friendly thing for human beings. And in a matriarchy, certainly, an abortion would be an absurd act. I’m also quite sure that it doesn’t have something to do with murder. I’m certainly not a Catholic, yet there’s something in the Church’s argument: that if you murder children up to the age of three months, you could equally say that people over the age of 90 or who have mental diseases should be killed; and that they should be killed in a clinical, pure way.

If you think that human life is sacrosanct, then you can’t be in favor of abortion, you can’t advocate it. And the dialectic is that in a social situation like ours, you have to ask politically for abortion not to be punished. Even if, outside the crude realism of our society, you are still in favor of abortion, you still have to explain both things.

If I can’t solve the contradiction then I have to explain it. And I tried to do it, on the one hand by showing Roswitha’s practice as something matter-of-fact; and on the other hand, when she’s drinking a cup of coffee after an operation, by showing that she’s practicing as a midwife. I don’t impose a moral standpoint. But on the visual and sensual level, the level of the camera, I make a plea for this aborted child. The more contradictory a situation is, the more contrasts you need to describe it. Neglect of the problem and sensual density are the two possibilities I can use.

Yesterday Girl

Like your other heroines, Roswitha is constantly obliged to change her type of work. We see her going from being a not unsuccessful abortionist, to being a very unsuccessful militant, to being a sausage vendor. We see Leni Peickert selling out to television, abandoning her Utopia, and taking a practical, compromised job, which, if she’s careful, may lead to the Ministry when she’s older. With Anita G. we have the extreme case of someone whose life is totally dictated by the chances she takes and the chances she chooses to ignore. You’re obviously preoccupied by the idea of people whose lives are completely alienated from their work.

Yes. They’re the majority in our society. We filmmakers have some opportunity to love our work, so we ought therefore to show all the more clearly that the greater part of work in our society is alienated. One particularly difficult thing is that if you want to make a film about labor in a factory, nothing happens; or, at least, nothing seems to be happening. Over 10 years a worker has quite a lot of problems, but you can’t combine them into an action story. That sort of action—which is interesting and gives pleasure, cinema-pleasure—is abolished in the factory. So that you can’t describe on film some of the major problems and experiences of our society in the same way that they exist in reality.

There’s another point. For instance, I’ve always found the industrial sector of Frankfurt very interesting. It’s the densest industry we have in Germany. It’s not like the coal industry in the North Rhine and Westphalia; it’s a mixed industry. For me it has more reality than, say, Munich. And I try to discover characters who’ve come through different milieux. There must be quite a lot of alienated and very singular persons who’ve come through several milieux. Usually, a worker or a university professor spends his whole life in one milieu, the one he’s working in, and he can’t cut through the other parts. And I think any one point of our society can only be real in combination with all the other parts. Most people are imprisoned in one milieu, and that’s a damaging experience—not good for film.

You say it’s good for people to experience more than one social sector, yet your heroines go from one job to the next without really gaining in experience. Because in order to show them being alienated from their work, you in fact reduce working as a nurse to working as a switchboard operator to working as an abortionist to working as a chambermaid. Of course they’re all jobs that belong to the zone of the underprivileged, and to that extent they are all the same. But you treat Lent Peickert’s pretensions to working in a privileged zone as being interchangeable with those of your less artistic heroines. Isn’t there a slight contradiction here?

Yes. The different social milieux are governed by the same laws. So on the one hand it’s necessary to know and observe the differences between them; on the other, to know some of the laws that govern them. And in underprivileged work, it’s always the same: you don’t get another experience if you change your job. There are some privileged types of work: art, for instance, or the circus; the Detective Squad in the Police; being a Deputy if you’re in Parliament. These “abstract” forms of work function differently but they’re “no exit” jobs; whereas underprivileged work, which has a lot of exits and also provides the motive for finding exits, doesn’t have the same freedom.

This brings us back to the question of false choices and the illusion of choice. There’s a blatant example in Yesterday Girl, one which echoes the mother’s choice in Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle. A mother is asked by visiting paratroopers or militaristic persons which of her two children she’ll sacrifice to solve the population problem; and she accepts this very phlegmatically and calmly.

What interests me most is showing that people don’t react to these false choices. The moral tradition and the political tradition are constantly producing them. Mitterand or Giscard d’Estaing is really not the choice. And I think it’s necessary to have in your nerves a sense of what constitutes a false choice. I mustn’t invent it. I can simply notice the inertia. People have false choices in their minds and in their feelings, and they know these choices are false. So they don’t react. The German soldiers march to Stalingrad, they’ve no reason to be there, and therefore they’re defeated. Napoleon’s Grenadiers marched to Moscow; they could be victorious anywhere in Europe that they thought they had a reason to fight; but in Moscow they don’t fight at all, they march back. And that’s a very realistic attitude. People are more clever, and societies are more aware than they think they are. Which is why I’m so interested in this inertia. It’s an unconscious protest against a false structure.

But your films seem to present a very pessimistic vision of the possibility of true choices. True choices nearly always seem to involve some kind of Utopia, something that doesn’t yet exist: “If only tomorrow could happen yesterday, or today could happen tomorrow.”

I believe very constantly and with good reason in Utopia; and I’d be a traitor to Utopia if I didn’t show it in reality. I’m not pessimistic at all. The more I believe in the possibility and the reality of the imagination and of Utopia, the more realistic and conservative I must be about Utopia. I agree with Leni Peickert: the longer we wait for Utopia, the better it gets.