“Great art is intelligent about Life.”—F. R. Leavis

I saw Munyurangabo at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival almost by accident. I knew nothing of it and had not even read the description in the 479-page program guide, which covered over 400 titles (all, of course, highly recommended!). I simply had time to pass between screenings, and its press show was just about to begin, with perhaps 20 people scattered around the auditorium. This is a common occurrence in a festival of this kind, where the policy is to squeeze in as many films as possible and hope for the best. There are long lines for the new films by established directors, all of which will be released within weeks or months; most of them have already been bought up by distributors before the festival ends.

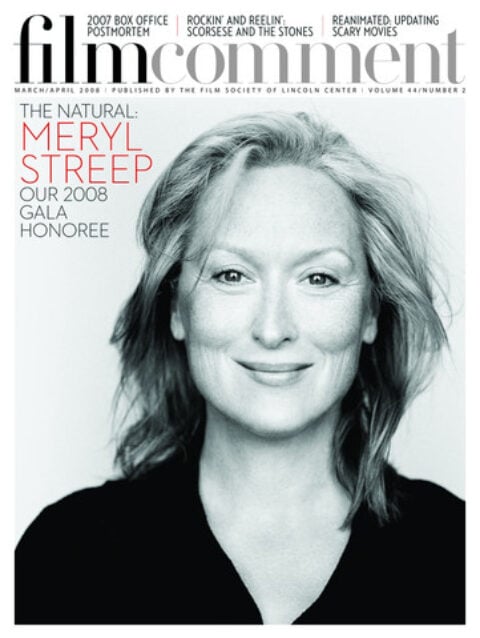

To me, Munyurangabo was a time-filler for which I had no particular expectations. It proved to be my favorite film of those I saw. I watched it again at a public screening in a large auditorium that was almost full and at which the director, Lee Isaac Chung, was present: word had got around. I have seen it several times since, courtesy of its director, who sent me a DVD. Chung, in fact, is American: he “grew up in Arkansas and studied biology at Yale University and film at the University of Utah,” according to the festival program guide. He and his wife went to Rwanda in the aftermath of the genocide, he to film, she to teach. Munyurangabo is his first feature.

The American cinema, in its more serious manifestations, has produced a number of critically acclaimed (and undeniably distinguished) films recently, works that address the state of Western culture with intelligence and a certain integrity. If I single out No Country for Old Men and Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, it’s because they are rooted in two of the foundations of American culture, respectively the Old West and “family values,” both now seen as irredeemably corrupted. To borrow from a Chabrol title, rien ne va plus. They are in obvious respects intelligent, yes. But “intelligent about Life”? I would say the reverse: they leave their audiences with nothing. We hear so often today of the “collapse of Western culture” that it comes to sound like a bit of cocktail party repartee, almost taken for granted, such an obvious fact of life that of course there’s nothing we can do about it, like global warming. Nothing could be more dangerous.

Munyurangabo also grows out of cultural collapse on a grand (and horrific) scale, and then proceeds to transcend it. A “small” masterpiece? Small—indeed minimal—in budget, no spectacle, no “cast of thousands,” with only a very few moments of (familial) violence, no sex, no recognizable actors, cast entirely with nonprofessionals. The early days of Italian neorealism offer perhaps the nearest precedent, but set, cast, and photographed in the aftermath of an admittedly very different war, internal rather than international.

Among the most remarkable aspects of the film is its total lack of condescension—none of the Noble American putting things straight for the ignorant natives. One would never guess, without prior knowledge, that the film was the work of an outsider. Chung, one might say, has given it to the people of Rwanda, allowing them their voices without intervention—that, certainly, is the impression the film gives, even as its complex narrative structure suggests otherwise. It draws together a range of traditional structures: 1) the male love story (not necessarily sexual), with its commitments, its tensions, its breakups; 2) the journey/quest narrative, with its diversions and stopovers; 3) the revenge narrative (very precise: the film opens with the theft of a machete; around the midpoint we learn what it was stolen for; at the end the machete is discarded); 4) the “family” narrative, which dominates the central (and longest) section of the film, and in which the political tensions ultimately erupt.

With limited space, I want to focus on the film’s last 10 minutes, following the apparently final breakup of the friendship between Munyurangabo and Sangwa, among the most moving in my experience of cinema. As this necessitates giving away much of its detail, those who have not yet been able to see the film might prefer to put what follows aside until that opportunity arises—though, so far, it has not been picked up for distribution.

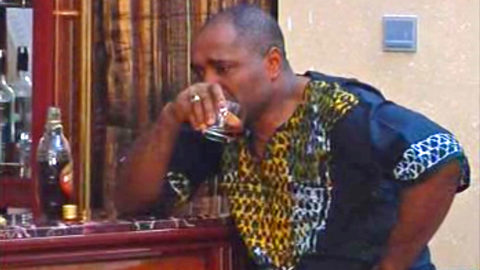

The final segment is preceded by a remarkable interruption in the narrative. Munyurangabo, when he reaches the town where the man who killed his father lives, stops for a drink at a roadside café before completing his mission. A young man suddenly appears in front of him, announcing that he is a poet and that he is going to recite, for practice, the poem he has composed for a public gathering. That this is a moment—a punctuation point—outside the narrative is underlined by the totally different camera style: a single long take in close-up, the camera tied to the movements of the performer. The poem amounts to a passionate, all-embracing demand for a new Rwanda, as a land of togetherness, freedom, unification, equality (including even the equality of women), and no more slaughter.

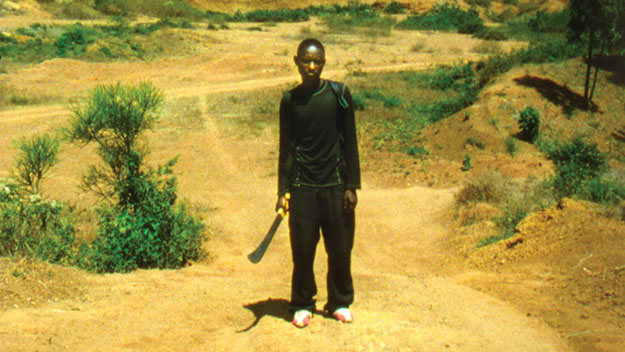

The message is apparently lost on Munyurangabo: we see him motionless in long shot at the top of a rise, set against a blue sky so dark it’s almost black, staring ahead, machete in hand. Cut to his view: a crude wooden house, which we guess is the home of his intended victim. As he approaches, he becomes increasingly hesitant and uncertain (under the influence of the poem?). Inside, he finds his victim, no longer the vicious murderer of his father but a helpless man in a bed on the floor. He is in the last stages of AIDS; he asks for water.

Outside, Munyurangabo is hesitant; birdsong, barely audible until now, suggests spring, new life. This triggers Munyurangabo’s mental journey backwards: we sense that it is not only because of the man’s helplessness that he spares him but the accumulated incidents of the entire film—the friendship with Sangwa, his experience of the family, the poem… We witness his long hesitation, alone in a neighboring field, then at night. There is a passage of “magic realism”: night in the fields; the disembodied presence of the dead father, reminding him that he is named after a Rwandan mythological hero; the father’s words culminating in the challenge “What is your battle?” It’s the final line spoken in the film. Then a dream: Sangwa in the Kigali neighborhood of Kimisagara, the two friends’ joyous reunion in the streets. Then rain, and the return to reality.

Munyurangabo is back at the top of the rise, looking at the house; there is no sign of his machete. We see him carrying out the plastic containers for the water; the birdsong (which sounds really present, not dubbed in) is louder than ever. We watch him filling the containers to the brim, almost lovingly; suddenly Sangwa is there, seated, a few steps behind him. The End. We are left to decide for ourselves: has Sangwa returned? Neither speaks, neither shows awareness of the other. A presence, a memory, an influence? Whichever you pick, it’s an authentically beautiful film. “Great art is intelligent about Life.”

(Note: I have not been able to trace the F. R. Leavis quotation to a precise source, but I hear him saying it. It may have been in one of his many lectures I attended at Cambridge University, England, almost 60 years ago…)