50 Years of Film Comment: Part Two

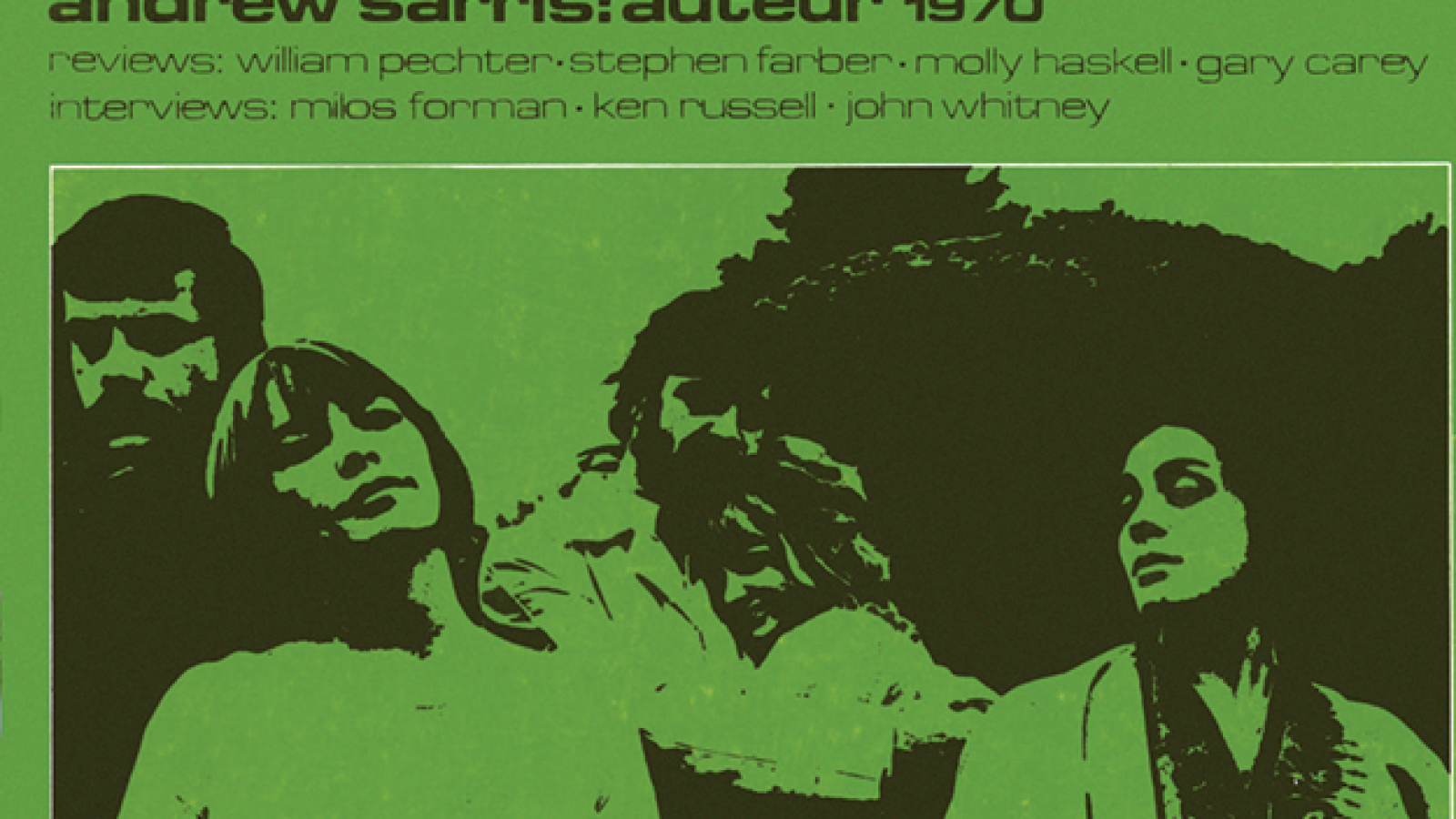

Now let’s see where we were,” begins Andrew Sarris’s “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970,” the opening salvo of FILM COMMENT’s first issue under Corliss, “when we were so rudely interrupted by the shrill cackling of the unbelievers.” This is as strange a way as any for a publication to usher in a new decade and a new editorship: not with a “where are we?” or a “where are we going?” but with a “where were we?” It suggests another question: to what extent was Corliss planning to carry over Hitchens’s editorial agenda, and to what extent was he picking up the thread of auteurism fostered in the pages of Film Culture and The Village Voice?

By the mid-Sixties, Hitchens had started to run features that wouldn’t have been out of place in Corliss’s FILM COMMENT—an extended interview with Fellini, an ecstatic piece on Dreyer’s Gertrud, Sarris paying tribute to Preminger. And by the end of the decade, during a year-long stretch of national-cinema-themed issues spanning Asia, Europe, Germany, Sweden, and elsewhere, Hitchens appeared to be warming up to the idea of the director as chief creative force behind a film. Nonetheless, running “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970” was a pointed gesture on Corliss’s part, a signal that a magazine previously allergic to “absolutes and essences” had finally committed to a single ethos. For its author, fresh from the triumphant publication of his era-defining book The American Cinema the previous year, the essay was both valedictory address and victory speech. For Corliss—one of Sarris’s former NYU students—it was a belated entry into a debate that appeared to have been all but won.

“As I said back in 1962,” Sarris wrote, “the auteur theory was proposed as a first step rather than a last stop.” Corliss had an Olympian next step in mind: to re-assess 50 years of American movies director by director, film by film, and shot by shot. Though there were echoes of Hitchens’s editorial approach well into the Seventies, with issues devoted to a symposium on porn and sexploitation, film and anthropology, and contemporary documentary practice, the magazine’s focus had already shifted decisively from the front lines of new independent film to the dustier territory of Old Hollywood. There were lengthy critical surveys of by-then-canonical directors (including Hawks, Hitchcock, Ford, Ophüls, Murnau, Welles, Chaplin, Lubitsch, and Cukor), features on selected international luminaries (Ozu, Dreyer, Vertov), and loving reappraisals of individual “film favorites.”

Throughout the Seventies, Corliss’s challenge was to steer the magazine between two extremes: on one hand pure auteurism, with its theistic sense of the director as an autonomous Grand Designer (a position that, as Robin Wood once pointed out, really amounts to “some absurd parody-concept that no one today could possibly wish to defend”); on the other, the more agnostic school of thought that positioned the director as a figure wrapped in so many economic, social, and ideological straitjackets, and skirted the question of film authorship altogether.

Throughout the Seventies, Corliss’s challenge was to steer the magazine between two extremes: on one hand pure auteurism, with its theistic sense of the director as an autonomous Grand Designer (a position that, as Robin Wood once pointed out, really amounts to “some absurd parody-concept that no one today could possibly wish to defend”); on the other, the more agnostic school of thought that positioned the director as a figure wrapped in so many economic, social, and ideological straitjackets, and skirted the question of film authorship altogether.

Yet, for Corliss, the primary aim was to promote autonomous, individual, free-thinking critical voices. That meant walking another line and avoiding both the highly technical semiological lingo coming into vogue among academic film journals, as well as the largely journalistic approach represented from 1975 on by the American Film Institute’s American Film.

Essentially, Corliss was a committed auteurist who objected to the exclusive, quasi-mystical status that auteurism traditionally conferred on the director. It’s fitting, then, that his second FILM COMMENT issue was a double-length celebration of the Hollywood screenwriter—as he put it 20 years later, “either an expansion of or an attack on the auteur policy,” depending on how you looked at it. (Four years later, Corliss would publish Talking Pictures—a revisionist history of American screenwriters that, in Raymond Durgnat’s words, “[did] for writers what The American Cinema did for their better publicized colleagues.”) A special on American cameramen followed in 1972. In the same spirit, from 1978 on, the magazine featured themed midsections that served as a clearinghouse for director dossiers (Herzog, Peckinpah, Truffaut), national surveys (contemporary Italian film, classical French cinema, Canada, Hong Kong), topical developments in film culture (television commercials, the advent of video, Turner Classic Movies), specialized areas (hardboiled Hollywood, the intersection of modern art and film, melodrama)—and sometimes a single extra-large story or monograph (future FILM COMMENT editor Richard T. Jameson on John Huston, Harry Shearer on The Jerry Lewis Telethon, Elliott Stein on movie palaces). Above all, this structural innovation, which varied in length from 9 to 38 pages (with an average length of 18), gave the magazine a way to honor film artists who had often been written off as craftsmen in the service of a director’s genius—including, but not limited to, editors, producers, art directors, makeup artists, and publicity-still photographers. That said, the goal was more to expand the concept of film authorship than to undermine the magazine’s auteurist commitments.

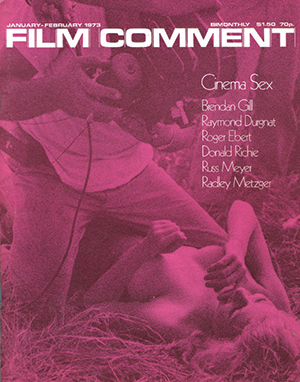

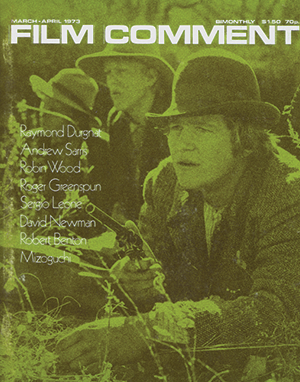

All the same, many of the magazine’s regular contributors shared a belief in the auteur as an all-powerful, godlike figure. Some of them took on a kind of auteur status themselves: each piece was an elaboration or revision of the one preceding it, an extension of the author’s personal philosophy, and a new installment in the serial narrative of his or her shifting relationship to the movies—all filtered through a catalog of pet obsessions and stylistic quirks. (Revealingly—and, today, perhaps unthinkably—the cover of the March/April 1973 issue listed eight names: four critics, then four directors.) In addition to Sarris, Corliss made steady use of Europe-based critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, former New York Film Festival co-director Amos Vogel, New York Times reviewer Roger Greenspun, industry reporter Stuart Byron, and film biographer Joseph McBride, and in 1973, he brought on Jameson as a regular contributor.

All the same, many of the magazine’s regular contributors shared a belief in the auteur as an all-powerful, godlike figure. Some of them took on a kind of auteur status themselves: each piece was an elaboration or revision of the one preceding it, an extension of the author’s personal philosophy, and a new installment in the serial narrative of his or her shifting relationship to the movies—all filtered through a catalog of pet obsessions and stylistic quirks. (Revealingly—and, today, perhaps unthinkably—the cover of the March/April 1973 issue listed eight names: four critics, then four directors.) In addition to Sarris, Corliss made steady use of Europe-based critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, former New York Film Festival co-director Amos Vogel, New York Times reviewer Roger Greenspun, industry reporter Stuart Byron, and film biographer Joseph McBride, and in 1973, he brought on Jameson as a regular contributor.

FILM COMMENT also had the distinction in the mid-Seventies of running four of the last pieces written by the legendary Manny Farber, all co-authored with his wife Patricia Patterson. (In 1977, he gave up writing on film and devoted himself to teaching and painting.) These essays—on Fassbinder, the 1975 New York Film Festival, Taxi Driver, and Jeanne Dielman—found Farber at the peak of his powers, blessed with one of the most distinctive (and idiosyncratic) voices in English-language film criticism. He wrote at once with the im-pressionistic fervor of a viewer still stuck inside the movie (each word is like a synapse firing), and the wit and rigor of a detached critic. The sharpness, precision, and meticulous refinement of his language aside, you’d think you were getting a direct feed from Farber’s subconscious. The Jeanne Dielman essay, Farber’s final piece of film criticism, starts off with a thrilling survey of Seventies art cinema, from Celine and Julie Go Boating to Beware of a Holy Whore. For Farber, Rivette’s film was “a new organism, the atomization of a character, an event, a space, as though all of its small spaces had been de-solidified to allow air to move amongst the tiny spaces”—a description that applies just as well to Farber’s porous, slippery sentences.

In 1973, the magazine did something it could only have gotten away with in its halcyon days of shoestring independent funding: it devoted the better part of two issues to a book-length study of a single filmmaker, written by a single critic. The filmmaker was King Vidor, and the critic was Raymond Durgnat, a British-born writer who would go on to become one of the magazine’s most prolific contributors. In his own words, Durgnat was “almost the last of the pre-Sixties limited auteurists, an Odd Man Out at bay against hordes of Hitchcocko-Hawksians.” Of course, he was also much more: a fierce intellect, a fount of citations, allusions, and references, and, at his best, a peerless wordsmith capable of Farber-esque twists of phrase: 12 Angry Men, we’re told, catches “the spats and ricochets and oddities of contact between men of different origins and styles, their sudden rages and mellowings and irrelevant alliances, their tensions zeroing in and zonking around from all kinds of odd angles.”

The above quote comes from Durgnat’s notorious 1977 critique of Howard Hawks. It’s a remarkable essay, and epitomizes Durgnat’s scattergun style in the way it leaps to and fro across the director’s massive filmography, keeping at least five or six strands of thought going at any given time. Three issues later, William Paul responded with an extended catalog of Durgnat’s factual errors—among other things, he’d confused the opening scene of Bringing Up Baby with George Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story—and suggested that his critical method wasn’t up to snuff. If anything, though, one of Durgnat’s biggest strengths as a critic was his recklessness; his willingness to overextend himself—a habit of coming at a film from so many different angles that they started to clash and contradict and burn each other out.

The above quote comes from Durgnat’s notorious 1977 critique of Howard Hawks. It’s a remarkable essay, and epitomizes Durgnat’s scattergun style in the way it leaps to and fro across the director’s massive filmography, keeping at least five or six strands of thought going at any given time. Three issues later, William Paul responded with an extended catalog of Durgnat’s factual errors—among other things, he’d confused the opening scene of Bringing Up Baby with George Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story—and suggested that his critical method wasn’t up to snuff. If anything, though, one of Durgnat’s biggest strengths as a critic was his recklessness; his willingness to overextend himself—a habit of coming at a film from so many different angles that they started to clash and contradict and burn each other out.

Where Durgnat was the magazine’s resident loose cannon, his compatriot Robin Wood was its torn conscience and public defender, struggling to come to terms with the virtues and limitations of FILM COMMENT’s brand of cautious auteurism at a time when auteurism, at least in certain circles, was already sliding out of fashion. From the start, his articles often took the form of loopy self-critiques and backhanded self-defenses. In 1972, for instance, one George Kaplan penned a thorough, unsparing takedown for FILM COMMENT of Wood’s book Hitchcock’s Films: “[Wood’s manner is] habitually calculated to intimidate; we are made to feel that, if we don’t agree with him about Hitchcock, we must be very stupid. If my own tone takes on a Wood-like (defensive?) edginess at times, let the reader attribute this to the fact that, after re-perusing his book, I have something of the feeling of an insufficiently-armored apprentice knight approaching the dragon.” How many readers remembered that “George Kaplan” was the name of the imaginary fall guy in North by Northwest, or realized that they had just read Wood’s merciless 7,000-word critique of his own book?

In his earlier FILM COMMENT pieces, Wood tended to focus on filmmakers whose worldviews weren’t far from his own: staunch humanists who celebrated human dignity in the face of adversity, and found triumph in tragedy and value in suffering. “The last moments of [the film],” he wrote of F.W. Murnau’s Tabu, “contain the essence of tragic experience, the sense of the potential value of existence expressed and affirmed even through irreparable loss.” Needless to say, the intellectual climate of criticism in the mid-Seventies wasn’t kind to morally serious auteurists with classical-humanist bents, at a time when academic film studies (represented chiefly in Britain by the influential journal Screen, and in France by a then-radicalized Cahiers du cinéma) lay in the shadow of Marx, Barthes, and Lacan.

In his later work for the reinvented, newly ideological Eighties incarnation of Movie, Wood would reservedly embrace some of the same structuralist principles he’d resisted throughout the Seventies. He dropped off FILM COMMENT’s radar until 2005, but not before giving the magazine a statement of intent it might have claimed as its own: “If I still have a role to play in contemporary film criticism, I am convinced it is that of a freelance operator, open—potentially at least—to all influences, critical of all influences, subject exclusively to none.”

In his later work for the reinvented, newly ideological Eighties incarnation of Movie, Wood would reservedly embrace some of the same structuralist principles he’d resisted throughout the Seventies. He dropped off FILM COMMENT’s radar until 2005, but not before giving the magazine a statement of intent it might have claimed as its own: “If I still have a role to play in contemporary film criticism, I am convinced it is that of a freelance operator, open—potentially at least—to all influences, critical of all influences, subject exclusively to none.”

In 1973, the magazine’s mounting deficits had become too much for Lamont. Joanne Koch, the executive director of the Film Society of Lincoln Center (whom Corliss had gotten to know while serving on the New York Film Festival selection committee), stepped up: by the end of the year, the organization had agreed to take over as FILM COMMENT’s publisher. This intervention was the latest episode in the magazine’s ongoing history of near-foldings and last-minute deliverances, and Koch would remain a staunch defender of the magazine until her retirement in 2003. In the Film Society, Corliss found a high-culture patron willing to give him a completely free editorial hand—all the benefits of going establishment, with none of the accompanying loss of critical face.

In the wake of its acquisition by the Film Society, FILM COMMENT did begin to feature vamped-up, albeit unsparing, New York Film Festival coverage (often in the form of dueling reports from James McCourt and Elliott Stein), profiles of Film Society Gala honorees, and—most significantly—increasing coverage of new films. More than a profit-minded compromise (although it was probably that, too, at least at first), this last choice could be interpreted as a conscious bid on Corliss’s part to restore some of the magazine’s former cultural relevance. If the movies seemed like blank spaces within impeccably described cultural contexts during the Hitchens era, Corliss’s early FILM COMMENT issues seemed too firmly entrenched within the movies themselves, far enough removed from the contemporary social scene that they could be analyzed comfortably in isolation as self-contained texts. Some would say entombed: “A director has to be 75 [to get into FILM COMMENT],” Positif editor Michel Ciment once told Corliss, “or dead.”

By the late Seventies, Corliss had become open to covering films ensconced in studio politics, messy interpretational questions, even violent controversy: see Wood’s defense of The Last House on the Left, or Roger Greenspun’s cover story on movie violence and Carrie. There were also signs that the magazine’s reverent attitude toward the classics was starting to relax. In 1978, Roger Ebert inaugurated the magazine’s Guilty Pleasures column—a FILM COMMENT tradition that’s survived to this day. Around the same time, the magazine welcomed a new cadre of contributors: Richard Schickel, a longtime critic for Time and Life magazines; David Thomson, a maverick British critic transplanted to the U.S., who would go on to make an indelible mark on FILM COMMENT in the Eighties; and the London-based, American-born Harlan Kennedy, bound for a decades-long stint as the magazine’s European editor.