50 Years of Film Comment: Part Three

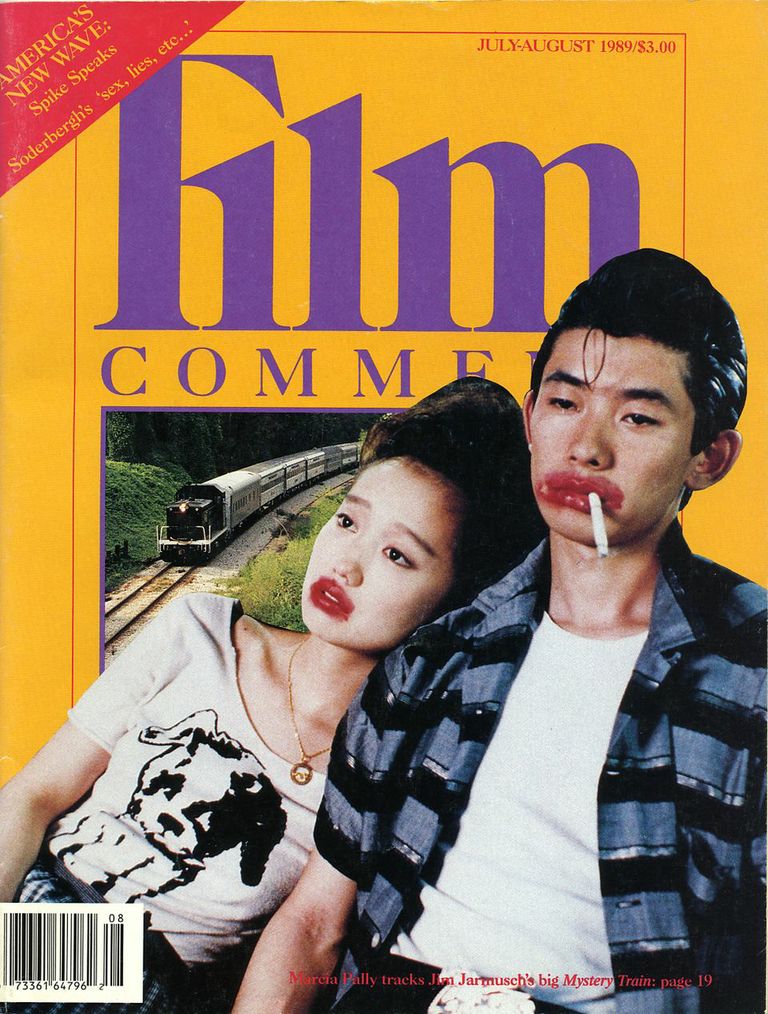

In 1980, Time hired Corliss as its full-time film critic. He would “hang on [at FILM COMMENT] in some editorial capacity or another” (as he put it in 1990) for another decade, but as the new gig started to siphon off more of his time and energy, it was senior editor and former Variety reporter Harlan Jacobson, appointed in 1982 at age 33, who picked up the slack. Although Corliss continued to regularly assign writers and contribute pieces throughout the Eighties, there was no mistaking the magazine’s increasing emphasis on cinema’s connections with broader currents of social and political thought. There was also some turnover in contributors. Longtime Corliss-era mainstays such as Greenspun, Durgnat, Wood, Sarris, and Rosenbaum moved on while more recent arrivals like Schickel, Thomson, Kennedy, Todd McCarthy, Anne Thompson, David Chute, Jameson, and Dan Yakir stayed put. At the same time a new generation of critics and correspondents came aboard, among them Marcia Pally, Marlaine Glicksman, Karen Jaehne, Pat McGilligan, Beverly Walker, Pat Aufderheide, Jack Barth, Marc Mancini, and Armond White.

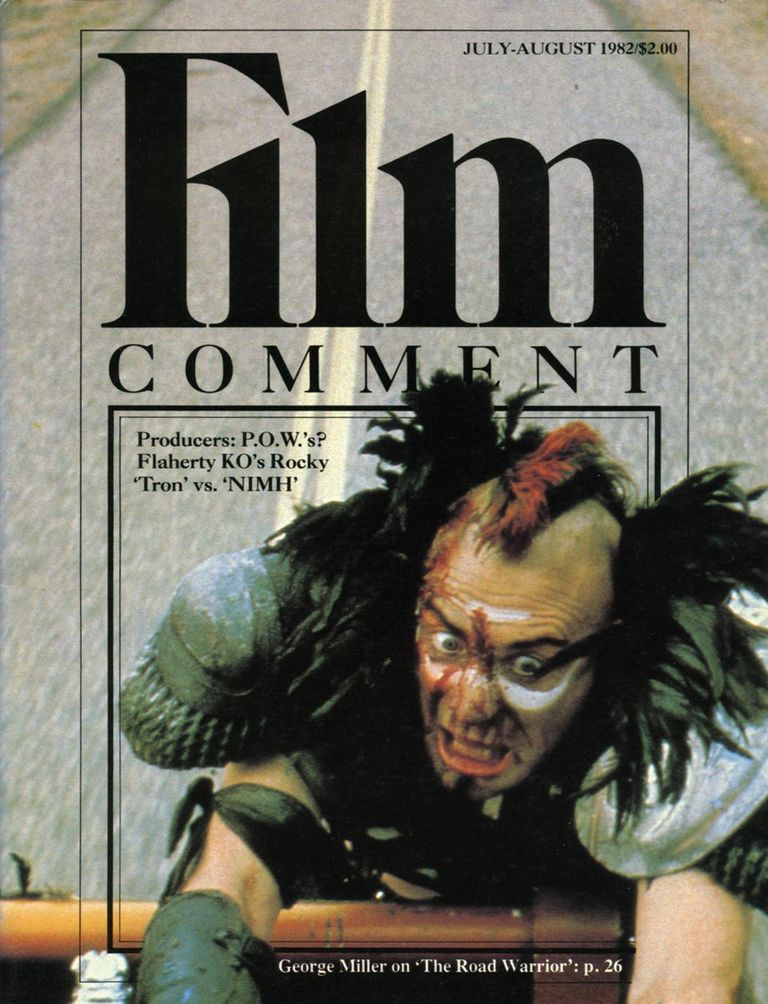

In Jacobson’s hands, FILM COMMENT’s tone became lighter, its writing fresher and quippier, and its subject matter more timely. A glance at the magazine’s contents gives a partial sense of the shift: on-set reports, Midsections on new visual media from music videos to arcade games, further Midsections on filmmakers and projects stuck in development hell, and articles on the future of moviegoing in a post-home-video world. One of Jacobson’s top priorities was to consider films within the context of the cultural moment in which they were made and received, which led to contributions from outside experts and cultural critics, including John Kenneth Galbraith, Donald Bogle, Elie Wiesel, Greil Marcus, Vito Russo, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and Alan Dershowitz.

Over the course of the Eighties the magazine also began doing high-profile interviews, as marquee talent (or their publicists, at least) came to understand that a FILM COMMENT interview would take them and their work seriously. The magazine’s credibility secured interviews with Jack Nicholson, Gene Hackman, Steve Martin, Goldie Hawn, and Cher, among many others.

Around this time, FILM COMMENT was also becoming attuned to identity politics, which held sway over much of the cultural conversation in the Eighties. (In a sense, Robin Wood’s 1978 essay “Reflections of a Gay Film Critic” was the turning point, with one eye fixed back on the magazine’s Seventies-era humanist streak, and the other anticipating its Eighties-era emphasis on social politics and cultural conditioning.) Under Jacobson, pride of place in the magazine often went to social-issue-driven pieces like 1984’s two-part symposium on pornography and sexual violence, occasioned by Brian De Palma’s Body Double. In addition to being possibly the only known instance of David Denby’s byline appearing alongside that of Screw magazine editor Al Goldstein, the symposium featured one of the magazine’s best interviews: Marcia Pally drilling De Palma about the representation of women in his films, which concluded with the director handing her pen and paper post-conversation (“expectantly, the way a priest motions for his congregation to rise”) and asking matter-of-factly: “So, Marcia, can we have a drink sometime?”

Around this time, FILM COMMENT was also becoming attuned to identity politics, which held sway over much of the cultural conversation in the Eighties. (In a sense, Robin Wood’s 1978 essay “Reflections of a Gay Film Critic” was the turning point, with one eye fixed back on the magazine’s Seventies-era humanist streak, and the other anticipating its Eighties-era emphasis on social politics and cultural conditioning.) Under Jacobson, pride of place in the magazine often went to social-issue-driven pieces like 1984’s two-part symposium on pornography and sexual violence, occasioned by Brian De Palma’s Body Double. In addition to being possibly the only known instance of David Denby’s byline appearing alongside that of Screw magazine editor Al Goldstein, the symposium featured one of the magazine’s best interviews: Marcia Pally drilling De Palma about the representation of women in his films, which concluded with the director handing her pen and paper post-conversation (“expectantly, the way a priest motions for his congregation to rise”) and asking matter-of-factly: “So, Marcia, can we have a drink sometime?”

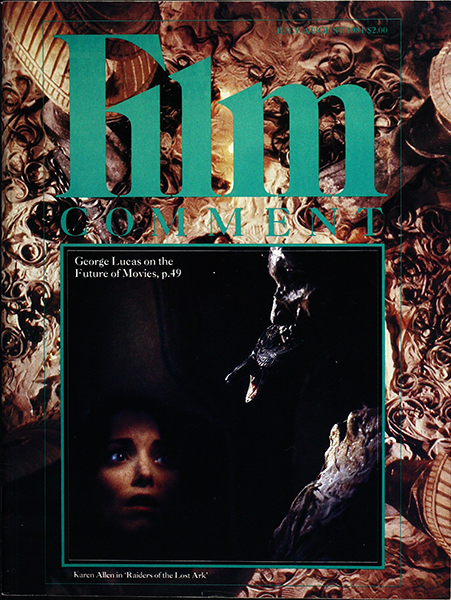

Given the chaotic state of the magazine’s production process (Corliss was far from the only FILM COMMENT staffer juggling his position with another job or two), it’s surprising how consistent the magazine stayed throughout the Eighties in mission, tone, structure, and look. Much of this was down to Jacobson’s organizational talents: he brought the magazine into the modern age with the purchase of a Wang computer, created flow sheets to track editorial operations, and brought on interns from Columbia and NYU, two of whom—Marlaine Glicksman and current editor Gavin Smith—later became assistant editors. It’s no coincidence that around this time, FILM COMMENT was starting to develop something like a house style: clear, punchy, ironic, lightly snarky. That said, Jacobson’s magazine also embraced a dizzying range of subjects: from David Thomson on the set of Footloose to pre-New Wave French cinema to workplace instructional tapes starring John Cleese; from the right-wing politics in Return of the Jedi to the depiction of German village life in Edgar Reitz’s 16-hour Heimat. Other highlights: a sympathetic, unexpectedly touching 12-page profile of the Ormond family who turned from making exploitation films to religious pictures after surviving a plane crash, Armond White and Donald Bogle on “race cinema,” Elliott Stein on India’s film industry (in three separate articles), Andrew Coe on Mexican wrestling films, and J. Hoberman on Indian movie-star-politicians, the history of Super-8 filmmaking, and the 1985 Budapest Film Week that included a “made-for-TV rock-documentary” by Miklos Jancsó “so hackneyed . . . [it] would embarrass Duran Duran.”

Some of Hitchens’s favorite subjects made a comeback in the Eighties. Censorship was once again a frequent topic, with two major features on the legacy of the Hollywood Blacklist, and one summer issue devoted to exploitation films past and present (complete with a garish, blood-spattered cover showcasing The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2). But where Hitchens’s FILM COMMENT had been self-serious to the bone, and arguably to a fault, Jacobson’s was ready and willing to deflate its own highbrow reputation. Take 1986’s Playboy-style centerfold of a pouting, fully clothed Dr. Ruth, or Matt Groening’s fake NYFF lineup a year later—including “Land of Ice, Land of Sighs,” a 285-minute-long Swedish drama noteworthy for containing “the longest human wail ever recorded on film.” Even the contents page was peppered with snarky gags and odd little free-associative descriptions. Here as elsewhere, Jacobson’s magazine was designed to reflect the spirit of the times: it was made for, and by, a generation trained to view any kind of political posturing or cultural pretension with ironic skepticism.

Corliss had placed a high premium on writers like Durgnat, Greenspun, or Rosenbaum who could slip effortlessly from subject to subject and tone to tone. Jacobson, on the other hand, relied frequently on writers with narrower, deeper areas of expertise. Under his watch, Chute became the magazine’s resident authority on exploitation and genre film, Pally its go-to source on gender politics, and White its most trenchant critic on ethnicity and race. At the same time, Jacobson was careful to make sure that his writers had a wide enough berth to cultivate their own recognizable prose styles. Even in his early thirties, Armond White, for one, could only ever write like Armond White. (It’s hard to imagine many other critics dubbing the list of apartheid victims scrolling across the screen at the end of Cry Freedom a “crude, tear-jerking effect [that] makes you think: These people died so Attenborough could win more Academy Awards.”)

Corliss had placed a high premium on writers like Durgnat, Greenspun, or Rosenbaum who could slip effortlessly from subject to subject and tone to tone. Jacobson, on the other hand, relied frequently on writers with narrower, deeper areas of expertise. Under his watch, Chute became the magazine’s resident authority on exploitation and genre film, Pally its go-to source on gender politics, and White its most trenchant critic on ethnicity and race. At the same time, Jacobson was careful to make sure that his writers had a wide enough berth to cultivate their own recognizable prose styles. Even in his early thirties, Armond White, for one, could only ever write like Armond White. (It’s hard to imagine many other critics dubbing the list of apartheid victims scrolling across the screen at the end of Cry Freedom a “crude, tear-jerking effect [that] makes you think: These people died so Attenborough could win more Academy Awards.”)

Then there was David Thomson, who was to FILM COMMENT in the Eighties what Robin Wood had been to the magazine in the Seventies: the regular contributor with more or less carte blanche to write long, playful, and sometimes hermetic; the critic-as-memoirist whose pieces tended to make most sense as episodes in a single, ongoing personal narrative; the unsparing self-analyst determined to challenge his intuitions and justify his enthusiasms. From there, for the most part, the comparison collapses. Thomson was as digressive a writer as Wood was schematic; where the latter’s prose feels carefully worked over, compressed for maximum clarity and precision, the former’s is nervous, pressurized, revved up, and spewed out—as if Thomson was desperate to pin down whatever association or impression had just occurred to him before another had the chance to displace it.

Whatever his immediate subject—the misogyny in Raging Bull; Marilyn Monroe; Stanley Cavell’s Pursuits of Happiness—Thomson’s FILM COMMENT output tended to be, at root, about a single thing: the emotional and moral toll of devoting one’s life to a world of images and screens. The most quintessential of these pieces was 1983’s “The Big Fix,” a breathless zigzag though, among other things, James Toback, Scorsese, Silk Stockings, James Dean, Altman, Celine and Julie Go Boating, Hitchcock, and Thomson’s beloved Citizen Kane. It’s the work of a critic for whom moviegoing was an exercise in sustained sexual frustration and occasional, intense release; an obsession, an addiction, a threat. (“Film is a drug,” he announces early on, “a fix we give ourselves, alone with the picture.”) More to the point, it’s the work of a critic so seduced by the world inside the frame that he had to be constantly checking himself, reeling himself back out of the screen—with the ultimate, impossible hope of reeling the movies out with him. “Sometimes it seems we live in frames and screens,” he wrote in 1982. “And it may be hardest of all for movies to break out of that relentless fallacy. But they must try.”

Whatever his immediate subject—the misogyny in Raging Bull; Marilyn Monroe; Stanley Cavell’s Pursuits of Happiness—Thomson’s FILM COMMENT output tended to be, at root, about a single thing: the emotional and moral toll of devoting one’s life to a world of images and screens. The most quintessential of these pieces was 1983’s “The Big Fix,” a breathless zigzag though, among other things, James Toback, Scorsese, Silk Stockings, James Dean, Altman, Celine and Julie Go Boating, Hitchcock, and Thomson’s beloved Citizen Kane. It’s the work of a critic for whom moviegoing was an exercise in sustained sexual frustration and occasional, intense release; an obsession, an addiction, a threat. (“Film is a drug,” he announces early on, “a fix we give ourselves, alone with the picture.”) More to the point, it’s the work of a critic so seduced by the world inside the frame that he had to be constantly checking himself, reeling himself back out of the screen—with the ultimate, impossible hope of reeling the movies out with him. “Sometimes it seems we live in frames and screens,” he wrote in 1982. “And it may be hardest of all for movies to break out of that relentless fallacy. But they must try.”

There had always been a faction of the board at the Film Society of Lincoln Center that felt the magazine was a financial drain and an unnecessary nuisance. At the end of the Eighties, a contingent of board members who seemed unhappy with FILM COMMENT’s direction engineered Jacobson’s removal. According to one version of the narrative, his dismissal was precipitated by the publication of his interview with Michael Moore in the November/December 1989 issue, in which he’d challenged the indignant director over Roger & Me’s chronological trickery. The media picked up on the interview, which altered the perception of the film in some quarters—Pauline Kael’s New Yorker review credited Jacobson with calling Moore out. In effect the interview had given a bloody nose to one of the hits of that year’s New York Film Festival, and two years after the film community’s outrage over the dismissal of longtime festival head Richard Roud, it’s possible that the last thing the Film Society and the festival wanted on their hands was another controversy. Opinions differ on whether Jacobson’s dismissal was a direct result of the supposed harm he’d done to the festival’s reputation—as a number of news outlets suggested—or whether the Film Society board was indeed simply displeased with Jacobson’s editorial vision, the Moore interview serving as the final straw. (The Film Society denied the charges, and Jacobson remained silent.)