50 Years of Film Comment

The story of FILM COMMENT’s first 50 years is, by one telling, the story of the general-interest film magazine: its birth at a time when serious filmgoing had never been more prominent in the cultural conversation; its rocky passage through changing tides of fashion and theory; its pragmatic adaptations and its stubborn refusals to adapt. By another telling, it’s the story of three generations of film critics: their personal philosophies, pet theories, changes of heart, private confessions and public disputes. By still another, it’s the story of what criticism has (and hasn’t) been to different people at different times: a platform for aesthetic judgments; a cultural litmus test; an ideological tool; a force for social change; a personal soapbox; a forum for debate. By yet another, it’s a messy, exhaustive history of the movies, caught with one foot in the medium’s ever-changing present and another in its ever-growing past. Throughout, it’s the story of an idea, or maybe an ideal: that a film magazine could be contemporary and timeless; rigorous and readable; discerning and unsnobby; and smart about movies, as it tagged itself for a few years in the 2000s.

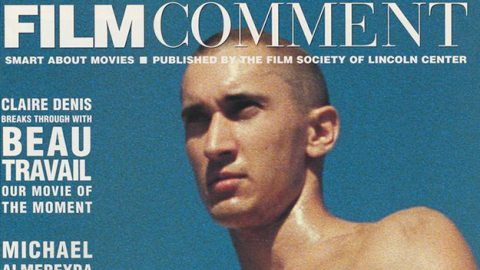

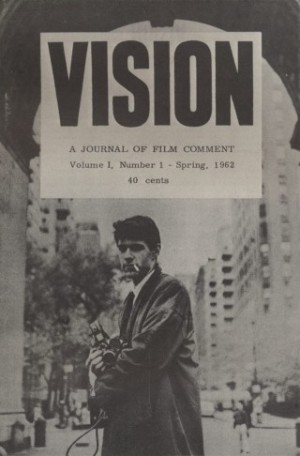

It began as a 36-page digest called Vision, which billed itself as “a magazine of film commentary.” By its third issue, the magazine—rechristened FILM COMMENT—had grown to an 8 x 11 quarterly with slim margins and sparse illustrations, packed with dense columns of typewritten text. One issue later, the font changed to something cleaner; gradually, the pictures multiplied and after a decade some turned to color. In the early Eighties, the layout got shaggier, with lone words (“widows”) occasionally trickling down into the crevices of text-wrapped film stills; over the next couple of decades, it would slowly straighten back out into symmetrical, orderly grids. Cover slots once reserved for obscure documentarians and venerable Hollywood icons started going instead to movie stars, from a blood-drenched Sissy Spacek to, in one unfortunate case, a hot-pink-infused Renée Zellweger. The typeface of the magazine’s name widened, expanded, shrank, contracted, and eventually narrowed into its present gapless lower-case.

And the words themselves? Context is all: in 1962, when 38-year-old founding editor Gordon Hitchens assembled the first issue in his Manhattan apartment with the help of a small group of friends and intimates, the movies had a hitherto unheard-of measure of cultural clout. It was the year of Jules and Jim, L’Eclisse, Vivre sa vie, The Exterminating Angel, and Ivan’s Childhood, a matter of months since Last Year at Marienbad had launched a thousand theses and Breathless a thousand student films. Serious film magazines were springing up by the year (Movie in Britain; New York Film Bulletin and The Seventh Art in the U.S.), and cinema studies departments were just starting to appear at adventurous universities.

Auteurism was the issue of the day. Andrew Sarris published “Notes from the Auteur Theory in 1962” in Jonas Mekas’s deeply influential underground journal Film Culture; in the spring of ’63, Pauline Kael would answer him in Film Quarterly (America’s longest-running magazine of film criticism) with her take-no-prisoners rebuttal “Circles and Squares.” The contention between the two critics was the stuff of legend. (“Her toleration of dissent,” wrote the typically mild-mannered Sarris in a slightly later FILM COMMENT, “is comparable in degree to Spiro Agnew’s . . . Her critical apparatus has more in common with a wind machine than with a searchlight.”)

Auteurism was the issue of the day. Andrew Sarris published “Notes from the Auteur Theory in 1962” in Jonas Mekas’s deeply influential underground journal Film Culture; in the spring of ’63, Pauline Kael would answer him in Film Quarterly (America’s longest-running magazine of film criticism) with her take-no-prisoners rebuttal “Circles and Squares.” The contention between the two critics was the stuff of legend. (“Her toleration of dissent,” wrote the typically mild-mannered Sarris in a slightly later FILM COMMENT, “is comparable in degree to Spiro Agnew’s . . . Her critical apparatus has more in common with a wind machine than with a searchlight.”)

It’s tempting to say that FILM COMMENT couldn’t have emerged from anything other than the over-stimulating atmosphere of the early-Sixties New York film scene. The magazine absorbed all of its era’s ideological tensions—white elephants versus termites, underground films versus commercial ones, filmmakers versus censors, Sarrisites versus Paulettes—but, uniquely, refused to align itself with any particular school of critical thought. It had the attitude of an earnest young freethinker: polemical, self-serious, bursting equally with detached journalistic observations and urgent calls to arms. “Tired of being a passive observer, the young person today occasionally becomes a participant in the world of film,” declares 18-year-old critic Gretchen Weinberg in a report on “The Teen-Age Box Office” for the first issue of Vision. “If the grown-ups—the filmmakers, the exhibitors, et al—want blood, we’ll give them blood—only, for God’s sake, let it be new blood!”

Hitchens’s FILM COMMENT tended to be equal-opportunity in its nose-thumbing, matching an almost total disregard for Hollywood with an equally strong, if more nuanced, distrust of the avant-garde. Its first issue took care to distinguish between justly valued experimental filmmakers and pretentious poseurs, but spent arguably more time disparaging the latter (whose films earned two separate comparisons—in a single issue!—to public masturbation) than praising the former. Hitchens’s sympathies lay with the activists, the muckrakers, the intrepid reporters, the anti-censorship defense lawyers, and the fly-on-the-wall documentarians: Vision’s first cover featured the trenchcoated, 19-year-old protest filmmaker Dan Drasin aiming a handheld Bolex square at the reader.

Occasionally, the magazine would overcompensate in its attempts to distinguish itself from the tightly knit New American Cinema crowd oriented around Film Culture and its editor-cum-godfather Jonas Mekas, with whom Hitchens had gotten his start in film journalism, editing newsletter copy. On the other hand, Film Culture favorite Gregory Markopoulos was a regular contributor, and Hitchens wasn’t beyond devoting lengthy features to the likes of Ron Rice and Bruce Baillie. (In 1970, he’d go one step further and guest-edit an issue of Film Culture himself.) Nor was the magazine immune to the kind of essentialist pure-cinema rhetoric it objected to when it came from the avant-garde: there’s a current of speculation over “what makes film film?” running through FILM COMMENT’s first few volumes, from Hilary Harris’s suggestion in Vision’s debut number that “illiterate films” might also be called “filmic films,” to Alan Casty’s charge five issues later that Ingmar Bergman had “forsaken the image for the word.”

Occasionally, the magazine would overcompensate in its attempts to distinguish itself from the tightly knit New American Cinema crowd oriented around Film Culture and its editor-cum-godfather Jonas Mekas, with whom Hitchens had gotten his start in film journalism, editing newsletter copy. On the other hand, Film Culture favorite Gregory Markopoulos was a regular contributor, and Hitchens wasn’t beyond devoting lengthy features to the likes of Ron Rice and Bruce Baillie. (In 1970, he’d go one step further and guest-edit an issue of Film Culture himself.) Nor was the magazine immune to the kind of essentialist pure-cinema rhetoric it objected to when it came from the avant-garde: there’s a current of speculation over “what makes film film?” running through FILM COMMENT’s first few volumes, from Hilary Harris’s suggestion in Vision’s debut number that “illiterate films” might also be called “filmic films,” to Alan Casty’s charge five issues later that Ingmar Bergman had “forsaken the image for the word.”

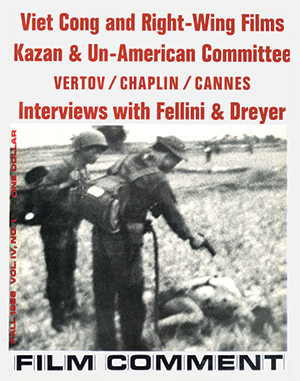

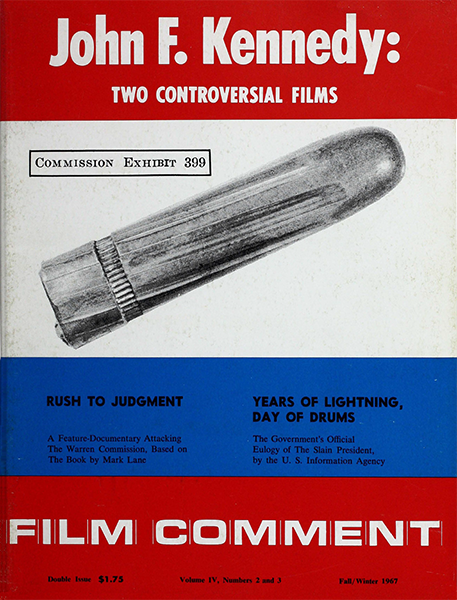

That said, FILM COMMENT in the Sixties tended to downplay formal questions in favor of, among other things, the role of film in society, the status of film in the courts, the Hollywood blacklist, the dismaying on-screen treatment of race, the staid on-screen treatment of sex, the evolution of cinema vérité, and the business of film production. One notable issue was devoted to the assassination of JFK, and several others focused on the war in Vietnam, including close studies of propaganda films by the United States Information Agency and North Vietnam. (In fact, Hitchens had worked for the USIA, as a filmmaker, a few years before launching FILM COMMENT.) Then there was the Summer 1964 issue in which Hitchens printed the responses to a questionnaire he had sent to a group of unsuccessful applicants for Ford Foundation film grants. The rejects included the Maysles Brothers, D.A. Pennebaker, Robert Frank, independent filmmakers Curtis Harrington, Michael Roemer, and John Korty, and such American avant-garde luminaries as Baillie, Brakhage, Breer, Jordan, Markopoulos, and Jack Smith (who responded with a drawing).

Hitchens’s magazine dealt most consistently with film as a cultural phenomenon. Reviews of new films were offered primarily within the context of festival reports, where industry politics, regional biases, and state-of-cinema pulse-taking arguably mattered at least as much as the merits of particular titles. Writers were chosen based on their technical experience as well as their critical credentials: in a contributor roster of nonfiction filmmakers (most notably documentarian James Blue), film editors, journalists, specialized scholars, and the occasional attorney, professional film critics were a minority.

All of which suggests the extent to which Hitchens saw criticism as a kind of journalism, an act of reportage. (The magazine also served as a semi-newsletter, peppered with updates on major censorship cases, announcements of new film groups, and details about screenings and print rentals.) Replying to a harsh letter in response to his extended interview with Leni Riefenstahl, which was perceived as excessively meek and uncritical, Hitchens responded with as close as he ever got to a statement of purpose: “We parlor-existentialists at FILM COMMENT live from day to day, only half-trusting ourselves but placing utterly no trust in the absolutes and essences that guide so many other magazines to the grave. For example: while Critic A in Magazine B froths at the mouth about Truth and Artistic Integrity, we demonstrate in dry, factual detail that American tax-payers are sponsoring a fake battle film that promotes the war in Vietnam. Readers can then make up what their sense of ethics requires of them, if anything. We’re simply the catalyst.”

All of which suggests the extent to which Hitchens saw criticism as a kind of journalism, an act of reportage. (The magazine also served as a semi-newsletter, peppered with updates on major censorship cases, announcements of new film groups, and details about screenings and print rentals.) Replying to a harsh letter in response to his extended interview with Leni Riefenstahl, which was perceived as excessively meek and uncritical, Hitchens responded with as close as he ever got to a statement of purpose: “We parlor-existentialists at FILM COMMENT live from day to day, only half-trusting ourselves but placing utterly no trust in the absolutes and essences that guide so many other magazines to the grave. For example: while Critic A in Magazine B froths at the mouth about Truth and Artistic Integrity, we demonstrate in dry, factual detail that American tax-payers are sponsoring a fake battle film that promotes the war in Vietnam. Readers can then make up what their sense of ethics requires of them, if anything. We’re simply the catalyst.”

At the time, the magazine was full of bold polemics nestled inside collections of “dry, factual details.” (Combing through FILM COMMENT’s early output one is hard-pressed to decide whether, at any given moment, the magazine is operating in its journalistic capacity, its critical capacity, or some combination thereof.) But this passage was especially revealing—and, as it turns out, prescient. Hitchens’s determination that the magazine remain stingy with its trust, unbeholden to any grand theories or critical fads, made it hard for FILM COMMENT to match the immediate influence or prominence of Cahiers du cinéma, Sight & Sound, or Film Quarterly. In retrospect, though, this early stubborn refusal to make short-term alliances or assume grandiose postures seems like the secret to FILM COMMENT’s survival.

Not that the magazine’s survival was ever easy, or guaranteed. Money was a constant problem. Hitchens financed the first couple of issues himself with the help of his friend and publisher Joseph Blanco; after Blanco dropped out, FILM COMMENT was at risk of folding. The magazine survived thanks to the intervention of Clara Hoover, an aspiring actress with a generous trust fund whose financial support carried FILM COMMENT through 12 issues and three crucial years. From a publisher’s perspective, Hitchens wasn’t easy to work with. Deadlines were missed, issues skipped, and few if any concessions made in the name of marketability: if Hitchens wanted to run a 20-page interview with anti-censorship crusader Ephraim London, then so be it. Exhausted, Hoover left the magazine in 1965.

For three more years, FILM COMMENT got by on grants and handouts; finally, in 1968, Boston-based occasional contributor Austin Lamont agreed to step in as publisher. By 1969, he’d assumed full ownership of the magazine. This put Hitchens in a dangerous position: his contract was up for renewal after a year, and his refusal to meet any publisher halfway on matters of general editorial policy—making deadlines, running shorter articles, expanding the magazine’s focus to include more familiar films—put him on shaky footing. Hitchens stood his ground, branding Lamont’s requests as “editorial interference,” and when his contract expired in mid-1970, it wasn’t renewed.

For three more years, FILM COMMENT got by on grants and handouts; finally, in 1968, Boston-based occasional contributor Austin Lamont agreed to step in as publisher. By 1969, he’d assumed full ownership of the magazine. This put Hitchens in a dangerous position: his contract was up for renewal after a year, and his refusal to meet any publisher halfway on matters of general editorial policy—making deadlines, running shorter articles, expanding the magazine’s focus to include more familiar films—put him on shaky footing. Hitchens stood his ground, branding Lamont’s requests as “editorial interference,” and when his contract expired in mid-1970, it wasn’t renewed.

Hitchens was replaced by Richard Corliss, a critical prodigy who, at 25, had already enjoyed a series of high-profile freelance gigs and a four-year stint writing for National Review. He was no stranger to FILM COMMENT’s pages: his thesis on the Catholic Legion of Decency had taken up nearly half an issue the year before he came onboard. “We talked,” Lamont later recalled, “and he seemed like the right guy.”