50 Years of Film Comment: Part Four

Conveniently, Richard T. Jameson, a longtime Seattle resident, had relocated to New York the previous year to review films for the short-lived New York arts weekly 7 Days. When it became clear that the Film Society was thinking of installing a new FILM COMMENT editor, Corliss suggested Jameson as a replacement—and the Film Society’s board assented.

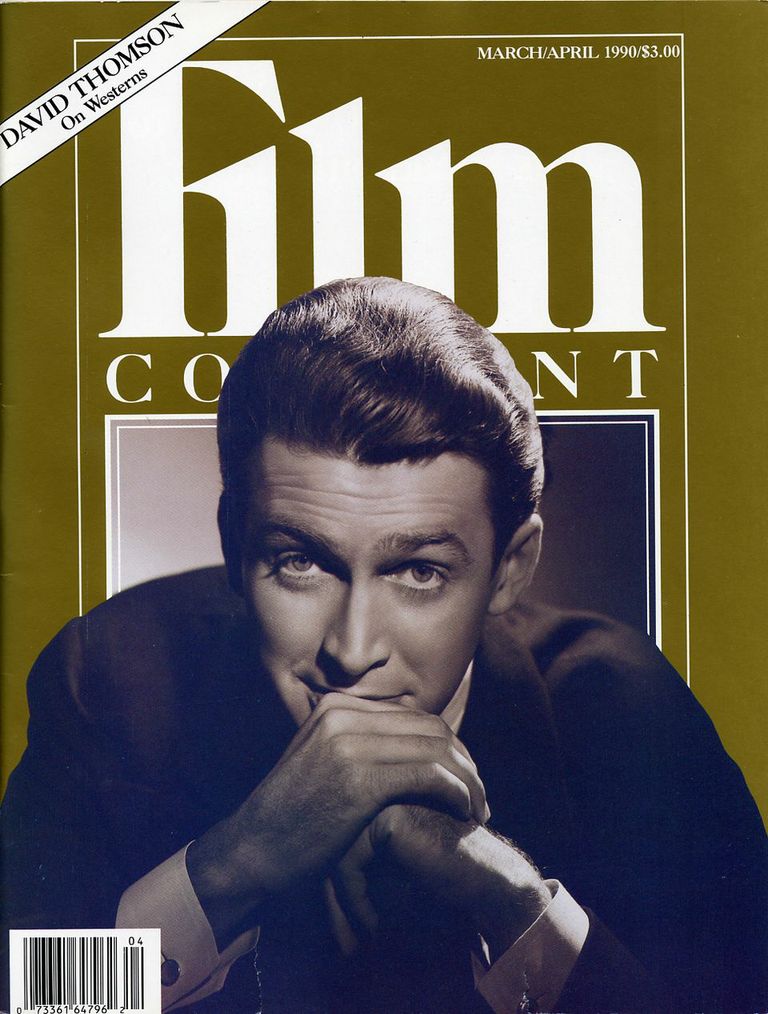

Because Corliss had stayed on the masthead in some official capacity—first as editor, then as co-editor, then as editorial director—for the duration of Jacobson’s stretch as de facto editor of the magazine (the masthead only finally listed him as such in the March/April 1989 issue), it was Jameson who was billed as Corliss’s first proper successor. The occasion was ripe for some not-so-thinly veiled valedictory addresses and torch-passing gestures, starting with Corliss’s prognosis for the future of film criticism (bleak, but with some glimmers of hope) and Thomson’s postmortem report on Westerns, epigraphed “for Corliss.” The irony was that, for all this talk of brave new worlds and fresh horizons and saying goodbye to “the man who made FILM COMMENT FILM COMMENT,” the magazine had never been closer to Corliss’s original vision. Under Jameson, classical filmmaking made an instant comeback: a quartet of pieces on James Stewart; a 20-page special section on Michael Powell; tributes to Garbo and Gardner and Stanwyck; Thomson singing the praises of Siodmak’s Criss Cross; and Donald Lyons doing the same for Preminger’s In Harm’s Way—and that in only three issues!

Corliss’s convincingly cranky takedown of televised, thumbs-up, thumbs-down film reviewing was rebutted in the following issue by Roger Ebert who shot back with a defense of Siskel & Ebert & The Movies, an attack on the modern star system, and a eulogy for college film societies. The two basically agreed more than they disagreed, as Corliss acknowledged in his next rebuttal, but that didn’t stop them from goading each other a little—even to the point of quibbling over each other’s respective word counts. Neither had the last word. But Andrew Sarris later intervened with an essay that didn’t so much resolve the debate as rewrite it. “Since I am personally acquainted,” he quipped, “with all three participants in this imbroglio [Corliss, Ebert, and, peripherally, Thomson] . . . I choose not to be excessively offended by their casual assumption that Andrew Sarris and auteurism are lost somewhere in the dear, dead past.”

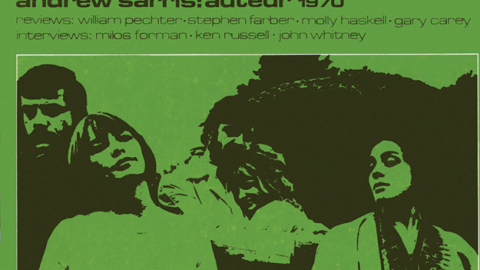

One could, perhaps, use Sarris’s on-again, off-again presence in FILM COMMENT as a barometer of the magazine’s stance on auteurism: he didn’t appear at all from 1982 to ’89, then resurfaced with a vengeance in the early Nineties, as Jameson steered the magazine back to the course of its Seventies glory years. That said, it would be reductive to measure FILM COMMENT’s development in relation to auteurism as if the latter were some kind of fixed and steady point. From the beginning, Sarris had emphasized that any auteurists worth their salt would constantly be challenging, revising, and expanding their positions. (Witness his two apologetic FILM COMMENT reappraisals of Billy Wilder, first in 1976, and again in 1991.)

One could, perhaps, use Sarris’s on-again, off-again presence in FILM COMMENT as a barometer of the magazine’s stance on auteurism: he didn’t appear at all from 1982 to ’89, then resurfaced with a vengeance in the early Nineties, as Jameson steered the magazine back to the course of its Seventies glory years. That said, it would be reductive to measure FILM COMMENT’s development in relation to auteurism as if the latter were some kind of fixed and steady point. From the beginning, Sarris had emphasized that any auteurists worth their salt would constantly be challenging, revising, and expanding their positions. (Witness his two apologetic FILM COMMENT reappraisals of Billy Wilder, first in 1976, and again in 1991.)

It’s important to keep in mind that Jameson took charge of FILM COMMENT at a time when auteurism had been thoroughly absorbed into the discourse of film criticism—so thoroughly that many of its own practitioners could write it off as a thing of the past. There wasn’t much left unredeemed in Thirties and Forties Hollywood, and every noir and weepie had earned some critical cachet by virtue of its age, its director, or its stars. In a similar way, the once-radical European modernists of the Fifties and Sixties—the Bergmans, Antonionis, and Godards—had seen their innovations incorporated into the basic stuff of art-house film grammar. It was hard to justify reappraising the classics once again without some kind of hook: a new theatrical release, a home video reissue, a restoration, an anniversary, a Lincoln Center Gala Tribute, a death. Even then, you ran the risk of looking like an out-of-touch nostalgist.

This must have been a frustrating situation for Jameson, a passionate, wide-ranging cinephile for whom any film—new or old, silent or sound, Old Hollywood or New Wave, canonical or underrated—was relevant as long as it had the capacity to surprise, perplex, delight, or provoke. “The cinema,” Jameson wrote in early 2000, “is an eternal present tense,” and that ethos would be as close as his FILM COMMENT came to having a party line. It was there in the annual “Moments Out of Time” section that Jameson and his wife, contributing editor Kathleen Murphy, compiled for the end-of-year issue: citations of images, lines of dialogue, scenes, camera movements, and characters lifted out of context, evoked and saluted on their own merits. It was there in the magazine’s functional design, in the abandonment of its long-running Journals department (with festival reports now simply classed as stand-alone features), and trademark Midsection—all of which suggested Jameson’s resolve to focus on the movies themselves, stripped of context, politics, and industry gossip. And it was there in the writing itself, replete with personal anecdotes, vivid descriptions, and detailed close readings.

By the second year of his editorship, Jameson had assembled a roster of steady contributors: holdovers from the Eighties (Thomson, Kennedy, White), several drawn from the ranks of Seattle’s Movietone News, which Jameson had founded and edited (Peter Hogue, Robert Horton), and a host of new arrivals. In the latter camp were Donald Lyons, theater critic for The Wall Street Journal, and New York Press regular Godfrey Cheshire, a champion of Iranian cinema.

By the second year of his editorship, Jameson had assembled a roster of steady contributors: holdovers from the Eighties (Thomson, Kennedy, White), several drawn from the ranks of Seattle’s Movietone News, which Jameson had founded and edited (Peter Hogue, Robert Horton), and a host of new arrivals. In the latter camp were Donald Lyons, theater critic for The Wall Street Journal, and New York Press regular Godfrey Cheshire, a champion of Iranian cinema.

If the magazine had a star contributor in the Nineties, it was Murphy, whose essays spoke in a richly textured, elevated register strikingly removed from the current of then-contemporary criticism. Occasionally she would risk letting her fondness for evocative metaphors and literary allusions overshadow her attention to the film itself, but she was always careful to snap things back into focus with a precisely noted detail or a well-placed confession—witness her accounts of falling head over heels as a young adult for “unfathered romantics” Matthew Arnold and Ingmar Bergman, or inching back to health after a serious illness with the help of Ophüls’s The Earrings of Madame de…

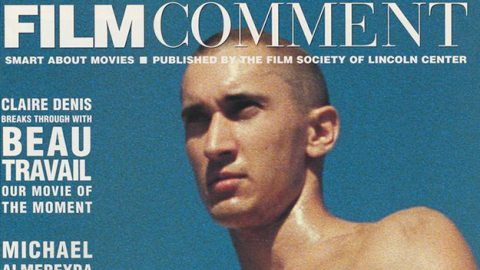

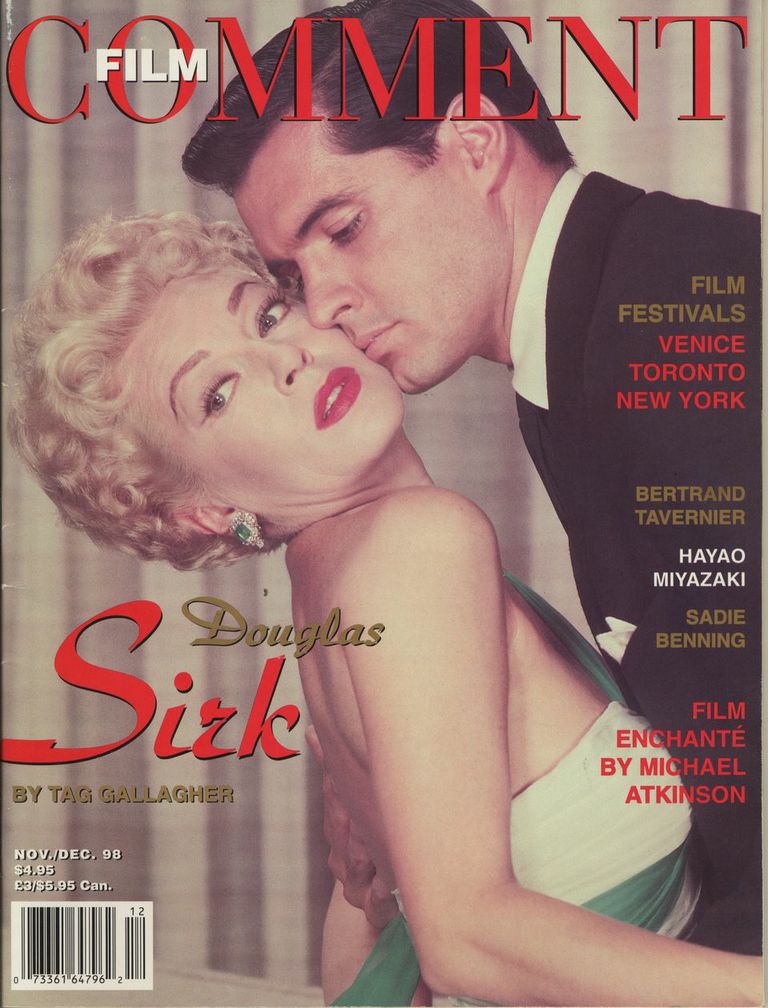

Where Jacobson assigned writers to stories as often as he accepted pitches, Jameson welcomed spec submissions and preferred to wait for his regular contributors to submit proposals—a calculated trade-off. The magazine’s overall sense of vision and purpose might sometimes slacken, but the hope was that, in exchange, each issue would have a democratic feel: a chorus of cinephiles taking consecutive solos, with the editor hovering in the background like a tasteful conductor. As long as he could maintain a high level of writing and a consistent set of critical values, Jameson was content to let each issue read like a medley of disparate pieces. Some high points: a pair of luminous personal essays from Thomson (on watching Meet Me in St. Louis with his 3-year-old son) and Phillip Lopate (on an early, transformative encounter with Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest); Geoffrey O’Brien on Fritz Lang’s Spies; Molly Haskell on Marguerite Duras; Kehr on Godard’s Contempt; Nestor Almendros on Eisenstein; Nicholas Ray on his own auteur status; Hoberman on early Yiddish sound films; Sarris on My Best Friend’s Wedding; Rosenbaum on Leos Carax; Schrader interviewing Aleksandr Sokurov; Tag Gallagher on Douglas Sirk.

Scanning the above list, it’s striking how many of FILM COMMENT’s regular Nineties contributors were established old-guard critics with reliable staff positions and/or steady teaching jobs. By the middle of the decade, though, they were sharing space in the magazine with newcomers such as London-based critic Richard Combs, fresh from a nearly 20-year run editing the British Film Institute’s Monthly Film Bulletin prior to its absorption into Sight & Sound, as well as younger freelancers like Chris Chang, Chuck Stephens, Michael Atkinson, and Howard Hampton—the latter an iconoclastic pop culture critic who combined a readiness to structure articles around Yo La Tengo lyrics with a knack for delightfully head-scratching turns of phrase: Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me’s Laura Palmer is a “petulant meat-puppet princess,” Blue Velvet’s Ben a “crazed-marionette pimp,” Viva Las Vegas’s Strip a “Duchampian assemblage of showgirl-flesh,” and Forrest Gump “a computer-generated cannibal eating the celluloid hearts of his precursors.”

Scanning the above list, it’s striking how many of FILM COMMENT’s regular Nineties contributors were established old-guard critics with reliable staff positions and/or steady teaching jobs. By the middle of the decade, though, they were sharing space in the magazine with newcomers such as London-based critic Richard Combs, fresh from a nearly 20-year run editing the British Film Institute’s Monthly Film Bulletin prior to its absorption into Sight & Sound, as well as younger freelancers like Chris Chang, Chuck Stephens, Michael Atkinson, and Howard Hampton—the latter an iconoclastic pop culture critic who combined a readiness to structure articles around Yo La Tengo lyrics with a knack for delightfully head-scratching turns of phrase: Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me’s Laura Palmer is a “petulant meat-puppet princess,” Blue Velvet’s Ben a “crazed-marionette pimp,” Viva Las Vegas’s Strip a “Duchampian assemblage of showgirl-flesh,” and Forrest Gump “a computer-generated cannibal eating the celluloid hearts of his precursors.”

This influx of new blood was the work of the magazine’s associate editor, Gavin Smith—with Jameson’s blessing. A British-born cinephile who’d come to the U.S. in 1986 on a Fulbright scholarship to study filmmaking at Columbia, Smith had taken an internship at the magazine on a whim in January 1987 and, after an apprenticeship as one of Jacobson’s assistant editors, made his name under Jameson with a large number of in-depth, high-profile interviews: Sean Penn, Abel Ferrara, Oliver Stone, Christopher Walken, Robert Duvall, Scorsese, Cronenberg, Tarantino, Godard—and many more. Behind the scenes, he also advocated for more coverage of international cinema and avant-garde film—to which Jameson readily agreed.

One of Smith’s recruits was New York-based critic Kent Jones. In 1995, after the two discovered their mutual admiration for a little-known, up-and-coming French director, Smith proposed Jones write a story on his career to date, and successfully lobbied to make it an assignment. The result was “Tangled Up in Blue: The Cinema of Olivier Assayas,” which established Jones as a permanent fixture of the magazine. He would subtly refine his prose style with each subsequent piece, but all things considered, it’s remarkable how much of his critical method was in place from the start. The extensive knowledge of film history was there, as was the careful balance between big questions (thematic, formal, political, cultural) and small, revealing visual details. But the biggest breath of fresh air was Jones’s voice: at once confident and searching, serious and playful, emotionally open and sharp in its ironies; equally given to risky flights of poetic fancy and plainspoken confessions; sharply attuned to a film’s emotional dynamics as revealed on the smallest of scales. The closest reference-point might be Manny Farber, who, Jones wrote in 2003, “once told me that the idea behind his writing was to get himself to disappear, and to get the object in question to shimmer with its own, unique sense of awe.”

In the late Nineties, FILM COMMENT once again started to fall out of favor with the Film Society board. The general quality of the writing notwithstanding, many felt that Jameson’s magazine had drifted too far from the organization’s mission, and they questioned its relevance. Moreover, the rising costs and mounting annual deficit led to renewed talk of shutting the magazine down. Jameson was fired and replaced by the 36-year-old Smith, who was given a trial period to turn things around.