50 Years of Film Comment: Part Five

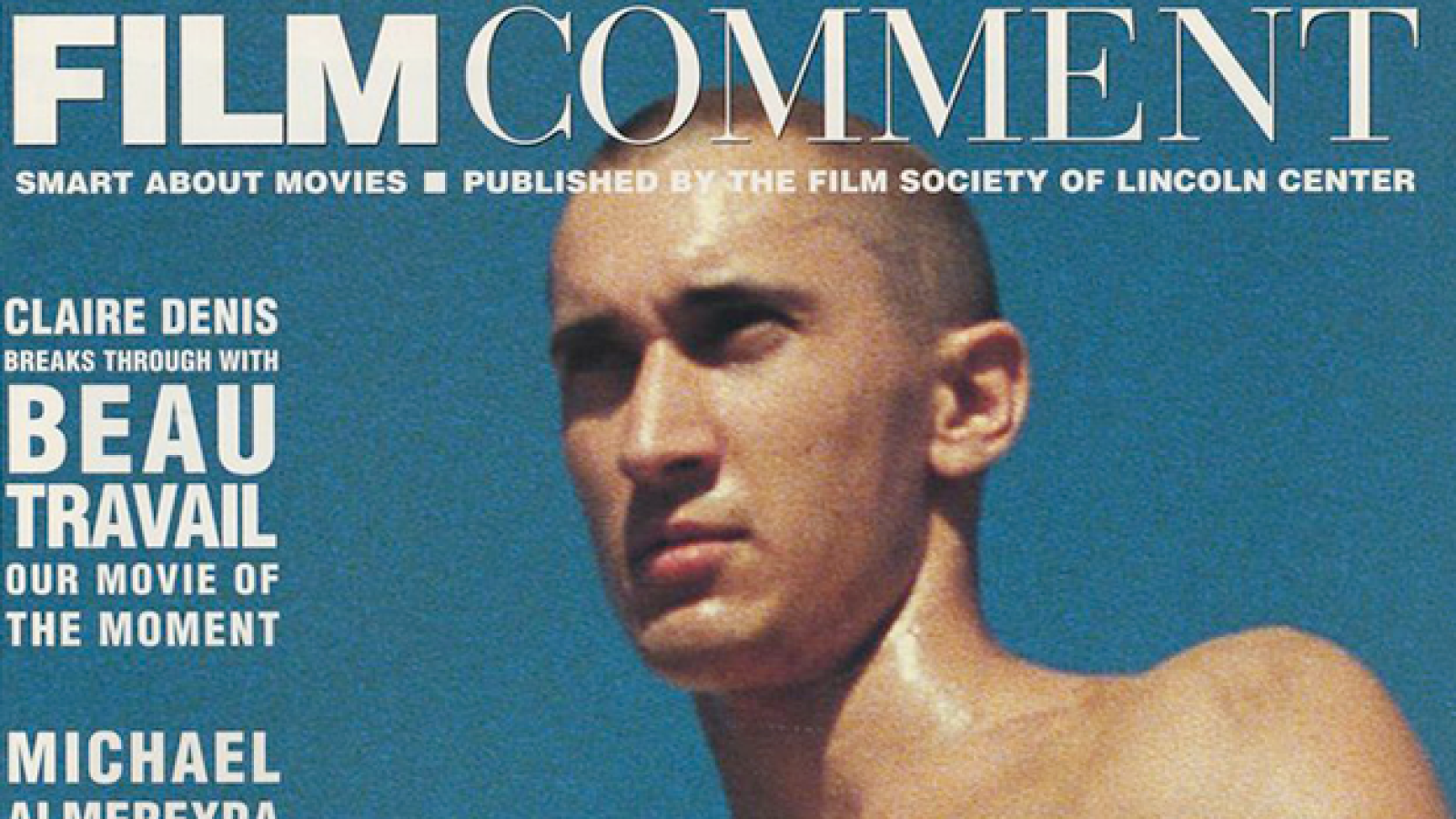

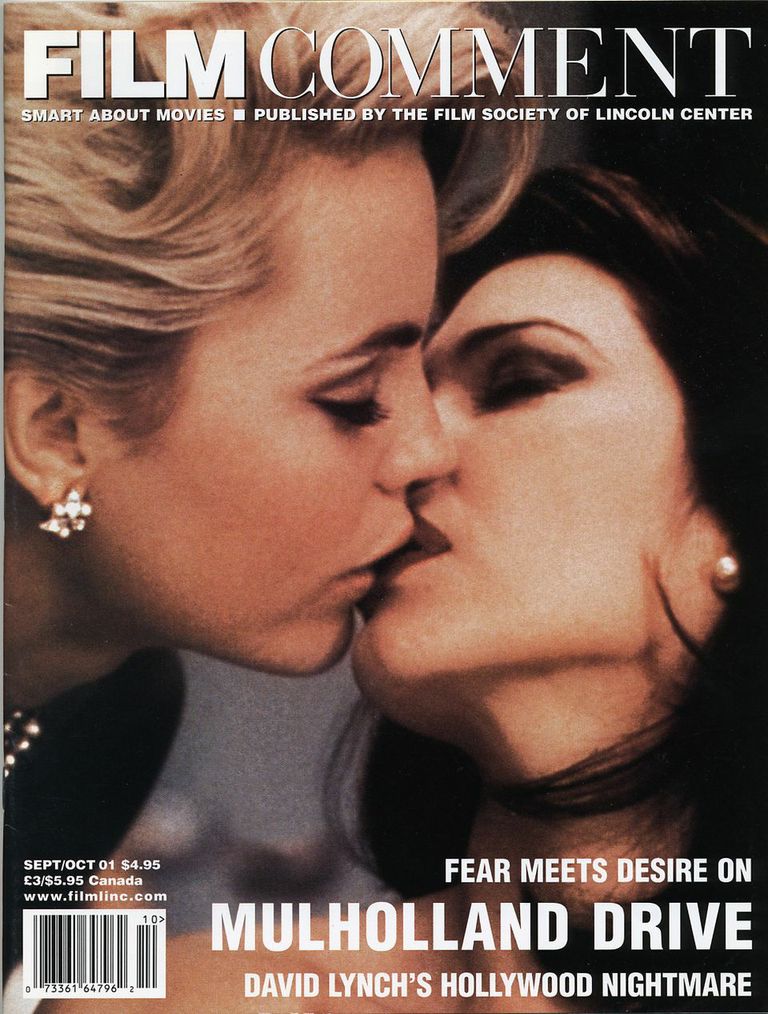

Smith had a year to refocus the magazine and he worked fast: the magazine’s May/June 2000 issue came with a sprinkling of new departments, an introductory flurry of tongue-in-cheek news bulletins, an expanded slate of festival coverage, and a beefed-up assortment of short reviews. The cover went to Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. As proof of the magazine’s democratic spirit, the next issue came emblazoned with a still from the Farrelly Brothers’ Me, Myself & Irene.

All this suggested a sharp departure from Jameson’s restrained, tactfully laissez-faire editorial style—a change borne out partly in the consolidation of the magazine’s emphasis on current world cinema, but also in its sharpened, narrowed focus, its heightened sense of urgency, its quickened pulse. Jameson’s sense of cinema as an eternal present, something to be explored patiently and expansively, had been traded for a resolve to catch film history while it was still in the making; to cue readers in on what films mattered most right now. In other words: out with Moments Out of Time; in with Movies of the Moment. “Contrary to those who say it’s all over,” Smith wrote in his first editor’s letter, “that the Golden Age of film and film criticism was the Seventies or the Sixties, or even the Forties, we think the here and now of movies is as exciting and challenging as ever . . . This is an era of too many dumb movies, cowardly distributors, and mediocre critics. Nevertheless, if you’re smart about movies and you have eyes to see (and if you’re lucky enough to be in a position to see), you’ll know that there’s a Golden Age going on right now.”

What, more specifically, was going on? Films from previously uncharted national cinemas, from Argentina to Austria to Central Asia to Romania were appearing on Western radar screens, Asian cinema was moving from strength to strength, French cinema was making a comeback, the American avant-garde was thriving, America was shaken by a national tragedy and plunged into a messy, irresolvable war, and the vague promise of digital filmmaking became a concrete reality. Smith responded to this last development with particular urgency. By the release of Dancer in the Dark in 2000, it was hard to ignore the fact that a major paradigm shift was afoot; two years later, by the time Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones showed what CGI could (and couldn’t) do, The Digital Question had become one of the defining issues of 21st-century film culture.

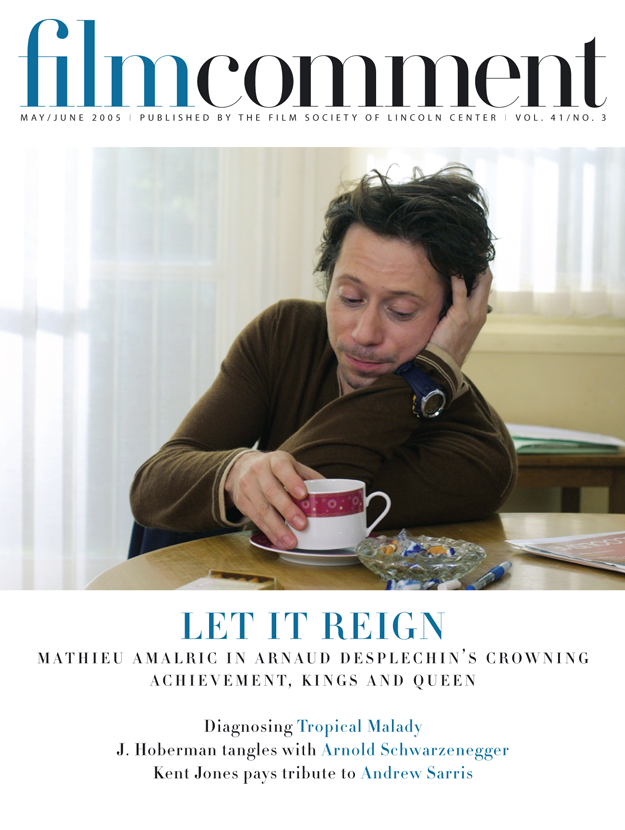

New times called for new structures—or, in some cases, old ones. The Midsection returned, if only sporadically, in the form of guest-edited dossiers on Bollywood, Japan, and Korea—and, in 2003, a special two-part tribute to Chris Marker, whose protean, globe-trotting essay films gave Smith’s FILM COMMENT an ideal subject, and something more besides: a role model. The long-abandoned Journals department was also revived, and re-cast as a forum for international critics to report from their home countries. For a few years, the magazine even ran new short fiction by the likes of William T. Vollmann, Barry Gifford, and Michael Tolkin. That department didn’t last, but others did: Olaf Möller’s revelatory, unapologetically esoteric reports from the front lines of world cinema, or the diptych Sound & Vision section, in which a rotating cast of contributors explore the points of contact between film, music, painting, installations, and video art. By mid-decade, after a major design overhaul, FILM COMMENT wasn’t much different in tone, look, or structure from the magazine you’re reading now.

New times called for new structures—or, in some cases, old ones. The Midsection returned, if only sporadically, in the form of guest-edited dossiers on Bollywood, Japan, and Korea—and, in 2003, a special two-part tribute to Chris Marker, whose protean, globe-trotting essay films gave Smith’s FILM COMMENT an ideal subject, and something more besides: a role model. The long-abandoned Journals department was also revived, and re-cast as a forum for international critics to report from their home countries. For a few years, the magazine even ran new short fiction by the likes of William T. Vollmann, Barry Gifford, and Michael Tolkin. That department didn’t last, but others did: Olaf Möller’s revelatory, unapologetically esoteric reports from the front lines of world cinema, or the diptych Sound & Vision section, in which a rotating cast of contributors explore the points of contact between film, music, painting, installations, and video art. By mid-decade, after a major design overhaul, FILM COMMENT wasn’t much different in tone, look, or structure from the magazine you’re reading now.

The contributor base, too, has stayed remarkably consistent, all things considered. As editor-at-large and now deputy editor, Jones has continued to be a steady presence, as has contributing editor Amy Taubin, a fixture of the New York independent and avant-garde film scene and Village Voice critic who joined the magazine in 2000 and remains one of its mainstays. A committed but undogmatic feminist, with a gift for unpacking a film’s narrative structure and a keen eye for visual detail, she embodies the magazine’s current attempt to balance the aesthetic and the political, never letting the one fully subsume the other. Also entering the magazine’s inner circle of writers: Phillip Lopate, the wide-ranging critic, teacher and essayist; Library of America editor-in-chief Geoffrey O’Brien; Nathan Lee, Jonathan Romney, Graham Fuller, Scott Foundas, filmmakers Guy Maddin and Alex Cox (who each had his own column), and Paul Arthur, for years the magazine’s top authority on documentary and avant-garde film, and a regular columnist with Art of the Real. (Arthur, sadly, passed away in 2008.)

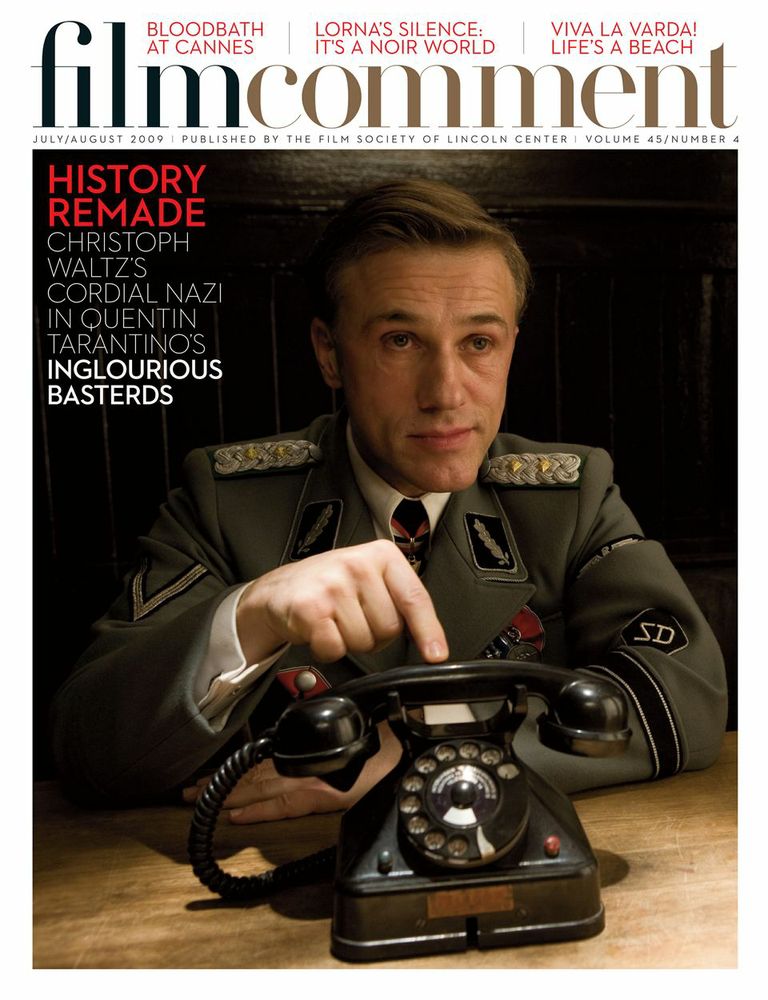

There are two sides to Smith’s FILM COMMENT that have always stayed intractably, intriguingly at odds. On the one hand, with its wealth of regular departments, its habit of sticking close to the twists and turns of the contemporary scene, its strict word limits, and its relatively stable issue-by-issue makeup (generally speaking, a three-way split between established auteurs, lesser-known independents, and genre filmmakers, with one or two slots reserved for reappraisals of lost classics and buried gems), the magazine is more rigorously structured and, in a sense, more predictable than it’s ever been. On the other hand, it’s also developed a fondness for hairpin turns and playful subversions. Just when you think you have it pegged, it goes and devotes 13 pages to a career overview of New German Cinema prime mover Alexander Kluge, or runs a feature on Bryan Singer’s Valkyrie back-to-back with one on James Benning.

At times FILM COMMENT’s present structure seems a little too restrictive and doesn’t leave critics as much room as they need to get personal or pursue a line of thought to the bitter end. But then you remember Lopate’s delightful anecdotal essay “On Changing One’s Mind About a Movie,” Chris Petit and Ian Sinclair’s extended e-mail duet on Christian Marclay’s The Clock, and Jones’s reflection on tossed-off, incidental portraits in films from The Musketeers of Pig Alley to Mean Streets and The Tree of Life. And then you remember FILM COMMENT’s many past excesses and indulgences, starting with Hitchens’s 20-page interviews and continuing through Thomson’s free-associative rambles. (Who could forget his extended survey on leading-man mustaches?) They were as perplexing and willfully reader-indifferent as they were revelatory. But times have changed, and if a magazine is born out of indulgence, gusto, and formal experimentation, it survives—and thrives—by tightening, compartmentalizing, and meeting its readers halfway.

At times FILM COMMENT’s present structure seems a little too restrictive and doesn’t leave critics as much room as they need to get personal or pursue a line of thought to the bitter end. But then you remember Lopate’s delightful anecdotal essay “On Changing One’s Mind About a Movie,” Chris Petit and Ian Sinclair’s extended e-mail duet on Christian Marclay’s The Clock, and Jones’s reflection on tossed-off, incidental portraits in films from The Musketeers of Pig Alley to Mean Streets and The Tree of Life. And then you remember FILM COMMENT’s many past excesses and indulgences, starting with Hitchens’s 20-page interviews and continuing through Thomson’s free-associative rambles. (Who could forget his extended survey on leading-man mustaches?) They were as perplexing and willfully reader-indifferent as they were revelatory. But times have changed, and if a magazine is born out of indulgence, gusto, and formal experimentation, it survives—and thrives—by tightening, compartmentalizing, and meeting its readers halfway.

The break between Smith and his predecessors is so sharp and well-defined that it’s easy to ignore just how much today’s FILM COMMENT extends from and pays tribute to its past incarnations. Witness Harlan Jacobson’s return to the masthead as a contributing editor in 2008, a year after he started writing his regular column Brief Encounters (Corliss-era writers Wood and Durgnat returned to write what would prove to be their final articles before passing away); or the late Andrew Sarris, with a column, The Accidental Auteurist, from 2009 to 2011; or Smith’s revival of Hitchens’s focus on documentary filmmaking. As for Corliss and Jameson, FILM COMMENT may be as far as it’s ever been from existing in an eternal present tense, but it’s rarely made the mistake of reading the past through the lens of the present, chucking the irrelevant stuff and keeping what seems modern and fresh. The magazine has always been strong at taking film history on its own terms—although whether it does so often enough, or rigorously enough, is up for debate.

In 2000, Joanne Koch wrote that “FILM COMMENT is now the only magazine of its kind in America—that is, a serious-minded but non-academic forum for discussion of movies as an art form and as a cultural phenomenon.” She wasn’t entirely right: Cineaste was (and is) as active as ever, Canada’s Cinema Scope had just started up the previous year, and Film Quarterly has never gone away. But her point is well taken: general-interest film magazines are now few and far between. The catch is that there’s more general-interest film criticism being written now than ever, on innumerable blogs and websites and online journals—some rigorously edited, some carefully self-reviewed, some haphazard, some half-formed. And that’s not counting tweets.

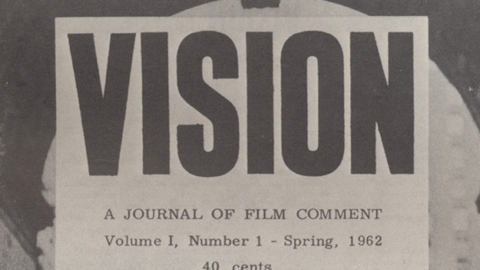

Much of this material is terrific. (It goes without saying that the majority is not—but that’s just as true of the movies themselves.) There are blogs that allow for the fascinating experience of watching a thoughtful, lively critic shape an opinion post by post, and labor-of-love publications beyond the profit motive. In comparison, FILM COMMENT is the only magazine of its kind in North America, print or otherwise: a glossy bimonthly with chic design published by a major cultural institution. Superficially, at least, it’s come a long way from three film lovers sitting on an apartment floor and proofing manifestos by teenage vérité directors. That isn’t to say that FILM COMMENT has lost its radically independent spark. But it is to say that the magazine occupies a singular and weighty position in today’s film culture—a position that comes with its own challenges and responsibilities.

Much of this material is terrific. (It goes without saying that the majority is not—but that’s just as true of the movies themselves.) There are blogs that allow for the fascinating experience of watching a thoughtful, lively critic shape an opinion post by post, and labor-of-love publications beyond the profit motive. In comparison, FILM COMMENT is the only magazine of its kind in North America, print or otherwise: a glossy bimonthly with chic design published by a major cultural institution. Superficially, at least, it’s come a long way from three film lovers sitting on an apartment floor and proofing manifestos by teenage vérité directors. That isn’t to say that FILM COMMENT has lost its radically independent spark. But it is to say that the magazine occupies a singular and weighty position in today’s film culture—a position that comes with its own challenges and responsibilities.

The principal challenge has been that of adapting to a critical landscape where two months count as an eternity and relevance seems measured by minutes of attention. To that end, FILM COMMENT now keeps a daily blog of new articles maintained by Violet Lucca and Nicolas Rapold, who manage to take each piece through a thorough editing process despite the demanding rhythms of online publication and the pressure of constantly looming deadlines.

The magazine’s main duty has been to prove that film criticism deserves to be written (and, for that matter, read) with patience, reflection, and dedication—the same way, in other words, that films deserve to be watched. FILM COMMENT, it seems to me, is one of the last places you can turn now to feel something like the thrill of reading a Manny Farber sentence, with its strange, pulsing, zigzag rhythms, or of watching from the sidelines as Robin Wood squares off against himself, or of feeling David Thomson slowly, painfully detach himself from the screen. At the very least, it’s an 8 x 12, full-color testament to the art of film criticism, sustained by the faith—occasionally misplaced, but more often than not wonderfully confirmed—that some movie reviews are worth holding on to, rereading, and savoring. And that, now more than ever, is no mean feat.