Why Grossing 2.5 Million Means Never Having to Say You’re Sorry

In the 10 weeks since its initial theatrical release, James Cameron’s Avatar has achieved mythic status in film industry history, amassing a record $2.5 billion in worldwide box office in that short space of time—$700 million in North America and an astounding $1.8 billion in the rest of the world. That it reached this position by surpassing Mr. Cameron’s 1997 film Titanic’s previous record worldwide total of $1.8 billion gives one some idea of how he doth bestride the film business like a colossus. But the key word here is “business.” As one who has been involved in the film business in one capacity or another for 35 years, I see Jim Cameron as the exemplar—make that the avatar—of today’s studio motion picture industry. To me, his films represent some of what is good and nearly all that is execrable about today’s corporate Hollywood with one giant exception—his movies make scads of money. (If you think, because they are hardly works of art, most of the others also rake in the dough, just check out the anemic profit reports from nearly every one of the majors.)

To illustrate just how much more successful his movies are than anyone else’s, the #3 title on the all-time worldwide list of box-office winners is the final chapter of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which has garnered to date $1.1 billion, or less than half of what Avatar has pulled in since its mid-December opening. But discussing the film’s financial results is of little direct interest to most of us, save for Fox executives, the film’s two outside financial backers, and Rupert Murdoch. (Yes, this manna is falling down on that ever-so-deserving clan, the Murdochs.) Oh, and of course James Cameron.

But this time he needn’t rely on mere money for affirmation—he had almost universal approbation from the front-rank critics as well, something that had previously eluded him. From Manohla Dargis (“Mr. Cameron is a filmmaker whose ambitions transcend a single movie or mere stories to embrace cinema as an art, as a social experience and a shamanistic ritual”) to David Denby (“the most beautiful film I’ve seen in years . . . luscious yet freewheeling, bounteous yet strange”) to Roger Ebert (“not simply a sensational entertainment . . . it is predestined to launch a cult”) to both the normally fairly sober trades, Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, there was near-unanimous opinion that Mr. Cameron had delivered the promised home run, not just visually, and not just in terms of its 3-D visual effects, but also “a fully believable, flesh-and-blood romance . . . a deeply felt love story.” But it was left to Time’s Richard Corliss to try to nail down the Best Encomium Oscar, while unwittingly defining my very concern: “For years to come, Avatar will define what movies can achieve.”

Well, these people were watching a different movie than I. (Fortunately a few of the reliably snarky British critics—from the non-Murdoch papers, to be sure—came through to let me think I wasn’t losing my mind.) I can assume that everyone has either seen Avatar—or been bored to tears by dinner companions relating the story of the Na’vi, their glorious planet, and how some thoroughly unpleasant earthlings are out to wreck it. What ensues is utterly illogical, thoroughly inconsistent, riven with hypocrisy and unbelievably clever in its manipulation of the audience. That it would work so well on critics who—in theory—should be inured to such shameless trickery is simply amazing.

Of course much has been made about the amazing technological advances embodied in the film’s special effects. As someone who is totally innocent of how these things are done, I accept as a given that they represent an extraordinary achievement. But would it be utterly churlish of me to point out that audiences had, as of 1926, only seen films that were both silent and in black-and-white? Exactly 13 years later, their eyes and ears (and hearts) were treated to Gone with the Wind. That filmmaking technology has, in another 70 years, brought us to Avatar doesn’t seem, to me at least, like all that great a leap forward.

(Not so incidentally, I will make a brave prediction—brave because chances are by the time anyone reads this, the following will have been proved either right or wrong. I am convinced Avatar will fail to win the Best Picture Oscar, for this reason if no other: no film since Grand Hotel in 1932 has won the top honors without being nominated for a single acting or writing award. That it will sweep the technical awards is a given, what with some 1,189 individuals named in the credits for visual effects alone.)

The film claims to be on the side of the gentle—and frankly primitive—Na’vi. But of course it is once again a coarse, young, ill-educated white male (a paraplegic on Earth, no less) from our inferior civilization who comes along, falls in love with the beautiful Na’vi princess (it’s never a commoner), and shows these supposedly superior creatures how to save themselves. Excuse me, but I think we’ve been here before. Dances with Wolves is the most recent and obvious parallel, but A Man Called Horse springs to mind, as does The Vanishing American (the superior 1925 silent with Richard Dix more than the 1955 Republic Pictures cheapie.)

Even those few critics who pointed out its failings from a dramatic standpoint fell over themselves in praise of its “beauty” and its miraculously understated use of 3-D. Indeed Cameron has created what The New York Times called “a meticulous and brilliantly colored alien world” that it found “strangely utopian.” What it didn’t seem to mention was that the film’s view of our world is distinctly dystopian, with the human race having made zero progress in roughly 150 years. Hell, they haven’t even passed Obama’s healthcare bill, as the hero has had to undertake this risky mission to Pandora to earn enough money to pay for an operation to restore the use of his legs.

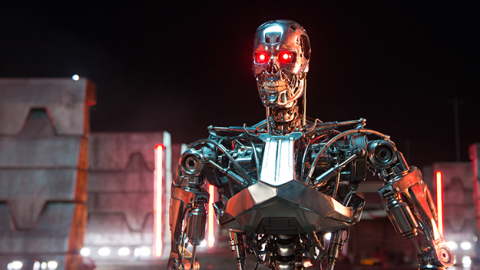

The fawning over Avatar’s visual beauty begs the key question: at what cost? I don’t mean to the News Corp. shareholders, but to the film’s storyline cohesion, to the absence of anything resembling normal acting that results from the use of motion-capture technology, and to the director’s willingness to match all that somewhat travelogue-ish earlier beauty with a 30-minute final (totally predictable, audience-pleasing) battle scene that can only be called downright ugly.

Much has been made of Mr. Cameron’s early fascination with the films of Jacques Cousteau and his own devotion to deep-sea diving. By happenstance, three days after watching Avatar in glorious IMAX 3-D, I found myself at the Museum of Modern Art, viewing a screening of World without Sun, the second feature by the Cousteau team. This now 45-year-old low-budget documentary was shot with the crude undersea equipment that Capt. Cousteau had cobbled together in the Fifties, with stilted and (mostly) dubbed dialogue and voiceovers, and with Buck Rogers–like equipment inside the bathysphere. Yet all of these simple elements somehow added up to compelling viewing. I sat there riveted, genuinely afraid that at least some members of the team were not going to make it back to the surface alive, whether from sharks, barracuda, or the bends. No such suspense permeated Avatar, as every plot element remained locked within a narrow range, familiar to every member of the adolescent male demographic, whose repeat attendance was so crucial to the film’s $2-plus billion worldwide gross.

My quarrel with the “advances” that CGI has brought to the movies is this: what do we now do for an encore? Where is the sense of wonderment that accompanied moviegoing in the now-distant age of optical effects, when we had to ask ourselves, “How did they do that?” Today every 12-year-old boy knows that the manipulation of a nearly infinite series of zeroes and ones has produced whatever effect he is viewing on the screen. Is our only choice now between Mr. Cameron creating an entire new world for $300 million or Mr. Emmerich, in 2012, destroying the one we have for $200 million?

The history of Fox’s commitment to Avatar is a complex matter, although in the rosy glow of its $2-plus billion worldwide box office no one will mention the distributor’s extreme nervousness about the project. As recently as three years ago, well into the lengthy gestation of the movie, Cameron was convinced that Fox was passing on the film and was trying to get Disney on board. At several junctures, Fox succeeded in getting Cameron and his producing partner, Jon Landau, to both trim the budget (at least on paper) and to significantly reduce their take if the picture failed to reach break even. On top of this, Fox brought in two investment funds for big chunks of the risk, as well as getting Cameron himself to be on the hook for a slug of its cost—rumored to be $60 million. Having the director knee-deep in all this sort of financial engineering assures that creative decision-making will necessarily be secondary to the demands of the broadest possible mass audience. One of those outside financiers was quoted as saying, approvingly of course, “This wasn’t purely a creative process for them, like it is with some producers. Jon and Jim absolutely understood the need to cater to audience tastes.”

But it isn’t the story’s lack of originality that is so depressing—it is its utter contempt for anything that truly resembles “civilization.” The writer of Avatar is of course Jim Cameron. The story sprang, full blown, from his head back in 1995. No Arthur C. Clarke for him. No Joseph Campbell to provide the myths that he could then bring to life. I suppose this lack of any literary antecedents doesn’t matter in this new post-literate—or is it pre-literate?—world. We are told that, back on an Earth we never see, nearly all forms of life have been destroyed by our rapacious search for minerals. But the world of the planet Pandora is just another Eden, scenically gorgeous, but devoid of anything that makes life interesting or fulfilling. Its inhabitants are engaged in a daily struggle for existence, however attuned to nature they may be. Their religion is some sort of animism, one that certainly appeared to me uncomfortably close to a low-budget Cecil B. DeMille paganism.

Some would ask, “Why bother treating such a film as if it intended anything other than to entertain the mass audience—and make pots of money, both of which it clearly does?” Because, thanks to the overweening success of Avatar and its aspirants, the major studios now see their only roles as allocators of capital to alchemists like Mr. Cameron, spinning box office gold from cinematic lead. That he is a positive auteur next to Michael Bay or Gore Verbinski is, sadly, not beside the point. Will we ever get a George Lucas making a new Star Wars with studio money again? Not very likely, despite that overall series being an even greater financial success than Avatar.

Will some current generation studio exec ever greenlight another 2001: A Space Odyssey? Don’t be absurd. Well, that glorious film was a major box-office hit in its day, grossing about eight times its cost of $12 million, about the same ratio as Avatar will achieve. The first screening of 2001 back in 1968 took place in Washington DC and was a total disaster, with half the invited audience never coming back after the intermission. But studios back then were run by people who, for a variety of complicated and not-so-complicated reasons, were willing to back their beliefs in films and filmmakers. The morning after that first nightmarish screening, the then CEO of MGM, the long since forgotten and distinctly un-mogulish Robert H. O’Brien, called Kubrick into his office to assure him that he would not impose the cutting of a single frame of the picture, and that MGM would spend whatever was necessary on the film’s distribution and marketing to make it a success. Other times, other customs.

I guess Mr. Cameron’s Avatar is right—we have met the enemy and it is us.