Klute: An Analysis

Why has Alan Pakula been hiding behind Robert Mulligan for so long? After producing a number of Mulligan’s best films, he made THE STERILE CUCKOO. In retrospect from KLUTE, that film’s resemblance to Mulligan appears misleading, and largely a matter of subject: Pakula’s attitude to his young people is notably tougher, less indulgent, than Mulligan’s. KLUTE is quite unlike Mulligan, and—sympathetic as I find Mulligan’s work—better than any Mulligan film I have seen. Its commercial success is in some ways surprising-not just because it proves the general public can show good taste, which has anyway been demonstrated countless times already (along with its opposite), but because its attitude is resolutely “traditional” or “old-fashioned”: the choice of epithet depending on whether you are for the film or against it.

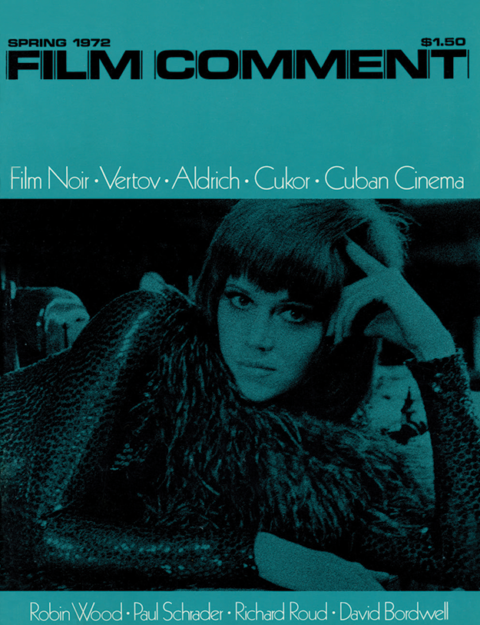

The title is (superficially at least) misleading, and may suggest that Donald Sutherland’s self-effacing performance, and the fact that Klute neither develops very far nor reveals himself very fully, are weaknesses in the film. In fact, the film is centrally about Bree Daniels (Jane Fonda). Mr. Sutherland and the character he plays perfectly fulfil their function in providing a (not unequivocal) representative of traditional stability and sanity; fuller exploration of Klute would be superfluous and would merely distract from the admirable clarity of the structure without adding anything essential to the film’s complexity. Indeed, it is part of the point that we don’t know more about Klute.

Part of KLUTE’s triumph is that it succeeds perfectly as a genre movie, a work of popular entertainment, a classical thriller of the Will-he-kill-her-before-they-get-him? variety, while remaining a work of the most serious commitments arising out of an awareness of essential contemporary moral issues. Further, there is no conflict between these two levels: indeed, it is quite wrong to speak of them as distinct “levels,” which always implies disunity in a work. One can’t dissect the film into the equation Seriousness + Entertainment = KLUTE. We are very far here from anything corresponding to Truffaut’s ludicrous recipe for commercial and artistic success a propos of LES BONNES FEMMES (THE SHOPGIRL VANISHES!).

Don’t tell me it would be inferior or vulgar done that way. Just think of SHADOW OF A DOUBT and Uncle Charlie’s thoughts: the world is a pigsty, and honest people like bankers and widows detest the purity of virgins. It’s all there, but inserted into a framework which keeps you on the edge of your seat. LES BONNES FEMMES is a calculated, well thought out, cerebral film. So why not make the extra effort which would have consisted of telling the story in entertainment terms, then superimpose on to this basic layer of the film a second and even a third layer? … (The New Wave, edited by Peter Graham, page 108.)—remarks showing a roughly equal incomprehension of Hitchcock and Chabrol simultaneously, though with their talk of “inserting into a framework” and “superimposing” layers they may help to explain the failure of THE BRIDE WORE BLACK.

Klute’s investigation of the disappearance of Tom Gruneman parallels throughout Bree’s process of self-discovery: parallels it so closely that the two are scarcely separable. Pakula’s use of genre conventions is masterly. The traditional climax, in which the heroine, alone with the killer and about to be murdered by him, is rescued by the hero at the last second, becomes also the culmination of this parallel development. (It is also an excellent example both of Pakula’s fairness with his audience, Klute’s intervention being not arbitrary but meticulously prepared, and the genuineness of the film’s suspense: it is so off-beat that for once we really think the heroine may get murdered before the hero arrives.) The two processes interact all the time. Klute’s presence-a moral presence as well as physical—is felt throughout as a determinant factor contributing to Bree’s reaction to what she sees, while Klute’s awareness of the relevance of each step in the enquiry to Bree herself steadily increases his concern for her.

The path the investigation takes is a step-by-step revelation of Bree’s potential future. The primary function of the scenes with her psychiatrist is to establish her as being poised at a possible turning-point in her existence. She can as well go one way as the other: a part of her genuinely wishes to give up her activities as call-girl, another part finds them a continuing. psychological necessity. It becomes clear to us (and to her) in the course of the film that they are a defense against any “dangerous” emotional commitment, offering her situations in which she can feel she has complete control, manipulating men who are dependent on her, without the necessity for any corresponding or answering dependence on her side.

Truffaut (and later Rohmer and Chabrol) saw SHADOW OF A DOUBT as constructed on the number two; KLUTE is constructed on the number three. It concerns three men linked by friendship: Tom Gruneman, whose disappearance after the brief pre-credits sequence provokes the whole action, Peter Cable, his murderer, and Klute, called in by Tom’s widow—with Cable’s support—to investigate. Klute’s investigation leads him to trace three prostitutes: Jane McKenna, murdered before the main action starts, Arlyn Page, murdered during the film, and Bree, potential murder-victim throughout. With Bree, Klute visits in turn three brothels, trying to find Arlyn Page. The brothels represent stages in Arlyn’s decline which Bree recognizes as, potentially, her decline also. The first is high-class, the clientele are the creme de la creme, and the proprietress tells Bree, the free-lance call-girl, that if she gets lonely “you’ll always have a home here.” The second, also a dance-hall, is run by a lesbian who remarks that she and Arlyn “could have had everything together,” as she clutches the hand of her current companion. In the third, full of overblown whores in various states of undress, with blue movies in an undarkened room amid other activities, the brutal-looking madam remarks of Arlyn, “Yes, she used to dress the way you do…” Counterbalancing this three-stage potential decline are Bree’s three attempts at finding more respectable employment: auditioning for a fashion magazine, visiting a theatrical producer (who emphasizes the necessity for self-knowledge), auditioning for St. Joan. Besides these major structural features, the motif recurs in minor ways. There are three scenes with Frankie, Bree’s ex-pimp-one where she visits him with Klute, one where, fleeing from involvement with Klute, she finds him in a club, one where she is planning to return to him to destroy her relationship with Klute. In the middle one of these, Frankie is the third of three men Bree tries to pick up in the club. There are also three scenes in which we see Bree with her analyst (though at other points in the film we hear their interviews without being shown them), which are answered structurally, by the three scenes where we are made aware that Bree, in her apartment, is being watched by the murderer. Where the echoes and correspondences of SHADOW OF A DOUBT (the number two) suggest symmetry or dialectic, the threes of KLUTE, combined with the classic thriller form of the investigation and with the recurrent motif of Bree’s analysis, represent dynamic progress.

The visits to the three brothels do not exhaust the exploration of Bree’s potential future. After them, at last, Klute and Bree find Arlyn herself, now a junkie. We saw Bree smoking marijuana earlier in the film to dull her consciousness of reality (and at the same time singing a revivalist hymn with the words “and at the beginning / The fight we are winning”—the moment beautifully expresses the dual impulse within her, rather as the hymn’s opening words, “We gather together to ask the Lord’s blessing,” poignantly counterpoint the aloneness of the image, camera tracking slowly back to show her isolated in long-shot). After her night out with Frankie, Klute finds her haggard and obviously drugged; Arlyn’s function as potential alter ego is implicit there, too. Arlyn has descended to streetwalking to supply her junkie lover with his fixes. The last stage of this descent-pattern isn’t witnessed by Bree, but is instead accompanied by her voice, in one of several superbly imaginative moments where sound and image are counterpointed. We see Bree with her analyst, telling her about her experiences of confronting “girls who could have been me.” Pakula cuts to Klute’s ascent in an elevator to the storage section in a morgue, where he is going to examine Jane McKenna’s few pitiful leavings. Bree’s voice continues on the sound-track: “I don’t really give a damn. What I would really like to do is to be faceless and bodiless and be left alone.” Jane McKenna appears in the film—she is as “faceless and bodiless” as Bree could wish to be, leaving little behind but bits of cheap jewelery and a rabbit’s foot.

The structure and style of the film throw into relief Bree’s visits to her analyst, giving them a special status. Generally, Pakula is very concerned with defining people by relating them to environment and decor: we learn a great deal, both intellectually and intuitively, about Bree’s life from the meticulously detailed decor of her apartment. We are carefully made aware of the apartment’s physical location in the street (next to a funeral parlour, whose sign, visually prominent in the foreground of the shot where we first see Bree arrive home, connects her at once with the threat of death, of becoming faceless and bodiless, and prepares for the startling use of the funeral procession past which Bree is followed by Peter Cable at the film’s climax). The analyst’s apartment is not placed in this way; we don’t know where it is, and we never see Bree traveling to it until her desperate search for help near the end of the film. And only at this stage (when the analyst is in fact absent) do we see anything of its decor besides a few children’s paintings on the wall behind Bree’s head. Our sense of time and chronology—again, very scrupulously preserved elsewhere in the movie—is also undermined here. In these interviews Bree is always dressed in the same clothes—we could almost be watching disconnected segments of the same session, were it not for the development implied in Bree’s speeches, a development intelligible only in relation to intervening events. Pakula seems generally to prefer two-shots to cross-cutting when shooting dialogue between two characters; in any case, we are always given a very precise sense of the physical space between them. This, again, is not so in the scenes with the analyst: the two women never appear in the same shot, and are never clearly related spatially through our awareness of their positions within the decor. Nor does Bree ever refer to her analysis when talking to others—we are vaguely surprised, at the end, to find that Klute knows the analyst exists. The effect is to remove these scenes to another plane: they become almost like self-communings, an effect specially emphasized by the use of Bree’s disembodied voice over scenes taking place at other times in other places. This counterpointing of action and reflection is a very satisfying way of rendering the film’s real inner narrative: Bree’s growth towards self-awareness and responsible decision.

Interestingly, however, the usual roles of action and reflection are here reversed: Pakula’s use of the voice-over technique at several points suggests that Bree’s actions are wiser than her words, that her healthiest instincts for life have developed beyond her conscious attitudes. We hear Bree’s voice telling her analyst about her disturbing feelings for Klute, her resentment of emotional involvement. “I want to manipulate him,” she says, as the images show her tenderly surrendering to his tenderness. This ironic counterpointing of voice and image reaches its most moving effect in the film’s last scenes. We see Bree sitting by the hearth, Klute in the rocking-chair—an archetypal image of domesticity. Bree’s voice speaks of the necessity for giving him up, as we watch her accepting his caress. Finally, we see Bree and Klute in the now bare apartment, ready to leave. The phone rings: a “call” for Bree. She tells the prospective client, “I’m leaving town right now and I don’t expect to be back.” Then, as the couple leave the flat, we hear Bree’s voice talking to the analyst: “I’ve no idea what’s going to happen. Maybe I’ll come back. Probably you’ll see me next week.” The last image is of the empty apartment, with just the phone on the floor. The fact that it is possible to argue as to whether this ending is ambiguous and open is evidence that it is not entirely unambiguous. Yet Pakula has taught us by this time to trust the images, not Bree’s words: the probability is that she will not come back.

The sense of potential interchangeability between the three prostitutes is reflected—albeit less overtly and decisively—in the three men, Cable, Gruneman and Klute. When the film opens, the three are seen sitting at the same dinner-table, members of the same family party. Cable and Gruneman are closely linked in the narrative, Cable having written the obscene letter attributed to Gruneman, and being in fact his murderer. In the scene where Klute undertakes the investigation, Cable is standing behind Mrs. Gruneman’s chair, in a position that would naturally be occupied by her husband. Before this, at the outset, the detective investigating Gruneman’s disappearance asks his wife whether her husband had any “sexual or moral problems or peculiarities”; then, revealing the obscene letter, tells her that “situations of this kind are not unique … A man may lead a Jekyll-and-Hyde existence and his wife would have no idea what’s going on.” Later, when Klute shows Gruneman’s photograph to Bree, her immediate response is, “Family-type man-it figures.” Obviously, she speaks from experience. The context of this last statement is significant. The incident occurs just after we have seen the murderer (at this point, identity uncertain) watching Bree from behind the fence on the other side of the street (a recurring visual motif—Cable is always seen watching through something, or is visually associated with barriers or enclosures). Shortly afterwards, in the same scene, we have Bree furiously asking Klute what’s his thing—and we see his impassive face, his only reaction the request, “Would you mind not doing that?”, as she unfastens the zip of her dress. Gruneman, in other words, could have abnormal traits, for all we or anyone else (including his wife) know of him; so could Klute. Cable and Klute are linked visually. Both are seen at points in the film as hazy reflections (Klute as he follows Bree after she has refused to answer his questions). Both men follow Bree and spy on her. The scene where Klute (as impassive investigator or voyeur?) watches Bree undress for old Mr. Goldfarb in his clothes workshop is paralleled at the end when Cable watches her from roughly the same place before attempting to murder her. In both cases the man’s presence is revealed by a close-up, Pakula using this to suggest at once a parallel and a distinction: Klute’s face is shown clear, without interventions, Cable’s is filmed through a window, blurred, as if to suggest Klute’s face seen as through a glass, darkly.

If Klute remains something of an enigma to the end, this is essential to the film’s meaning. Bree’s question—”What’s your thing, Klute?”—is never answered. Pakula leaves us free to assume, if we wish, that Klute and Tom Gruneman are indeed free of sexual abnormalities. But an alternative way of answering Bree is reserved for the film’s climax, its most electrifying moment. Cable, confronting her in Goldfarb’s office where she earlier provided the old man with his harmless and (transitorily) comforting diversion, turns her whole sexual philosophy back upon her. Bree contributed to the release of his repressed tendencies to violence and sadism; she has her share in the responsibility for the deaths of Arlyn Page, Jane McKenna, Tom Gruneman. Cable tells her, “I’m sure it comes as no surprise to you when I say there are corners in everyone-little sicknesses, weaknesses-that should never be exposed. I was never aware of mine until you brought them out.” Then he plays her the tape recording of Arlyn’s death. The point was already implicit earlier in the film when Bree, returning with Klute to a wrecked flat and defiled underwear, had to hear over the phone her own tape-recorded voice saying, “You should never be ashamed … Nothing is wrong … Do it all, let it all hang out.”

But more than this: Bree’s activities and her conscious attitude to them are related to the whole concept of “permissiveness,” of the desirability of casting off all inhibitions, realizing every desire (however perverse), doing your thing unreservedly. The tape-recorded speeches that obsess Peter Cable, at once alluring and mocking, also haunt the entire film: “One should be free of clothing and inhibitions … You should never be ashamed of things like that … Nothing is wrong … I think the only way any of us can ever be happy is to do it all, let it all hang out … ” I cannot help thinking of the doctrines of Wilhelm Reich, as presented (I am not in a position to say how accurately) by Makavejev: KLUTE and WR: MYSTERIES OF THE ORGANISM, two distinguished contemporary statements about sexuality, stand as polar opposites, representing the conservative and radical positions respectively—positions embodied in their form as much as their content. It is not the film critic’s business to adjudicate between rival and moral positions, except in so far as these are realized in their respective films: what concerns him, that is, is the convincingness of the realizations. Reduce these two films to messages, and the Makavejev is certainly the more appealing-its basic assumption being that happiness through sexual liberation may be possible, while the assumption of KLUTE is that it probably isn’t. WR is an extraordinary film inviting a complex and detailed analysis: brief comment runs the risk of over-simplification. It seems valid, however, to express some anxiety (contrary to the almost unanimous and unquestioning acclamation with which the film has been received) at the virtual disappearance in WR of certain qualities strikingly present in Makavejev’s previous work: the tenderness and sense of human dignity that in SWITCHBOARD OPERATOR were associated with the film’s more ‘traditional’ elements. In WR such qualities are restricted, again, to the most inhibited character, and allowed expression only after he has cut off the heroine’s head with an ice-skate. The film comes dangerously close to rendering sexuality merely trivial or ridiculous-to the extent that, granted the obliqueness of Makavejev’s method and the possibility of ubiquitous irony, one is tempted to take this as his real point and read the whole film in a sense contrary to its apparent drift, though such a reading is only possible, I think, by means of a rather extreme application of the principle of trusting the tale, not the artist. Perhaps tenderness and human dignity-and deep emotional commitments-are “old-fashioned” illusions we shall have to do without; though they are not to be tossed aside too lightly, a warning which it is the purpose of KLUTE quite unrhetorically and unpretentiously to assert.

Clearly, the description of KLUTE as traditional needs modification: its attitudes are not simple. The lines about “corners in everyone that should never be exposed” cannot be taken simply as the message of the film, as they are spoken by a pathological murderer in self-justification. Against them must be set, for instance, the tender pathos of the scene with old Mr. Goldfarb, and Bree’s impassioned defence of her visits to him (“His wife’s been dead seven years and I’m all he’s got; he’s completely harmless, he never lays a finger on me.”) We are also free to infer that Bree herself needed to pass through her call-girl phase, to “do it all, let it all hang out,” before she could grow to the maturity necessary for the emotional commitment of a permanent relationship. Certainly, the film is totally free of “old-fashioned” moralizing, and its structure leaves the viewer with a measure of freedom, the parts commenting on each other in a complex way that precludes reduction to any simple message. Its overall drift is, however, clear enough: Bree’s permissiveness is revealed as a kind of cowardice, an evasion of and defence against the potential pain and potential fulfillment of deep emotional commitment. To describe KLUTE, as Tom Milne does in Sight and Sound (Autumn 1971 ), as a film noir strikes me as willfully perverse. The ending is as optimistic a one as an honest contemporary film can possibly have.

KLUTE is built on a most beautifully constructed scenario, but it never appears merely a screenwriter’s film. If it is too soon to be sure of Pakula’s precise identity as an auteur, it remains true that KLUTE belongs, like any other great movie, to its director. The most flawlessly constructed script will not automatically produce a flawlessly constructed film. One never feels in KLUTE that Pakula simply took over and “realized” someone else’s work: the realization is too sure and too inward, the emphases too exactly judged, for one to question the director’s personal involvement. KLUTE seems to me as fine a film as any the American cinema has produced in the past decade.

Robin Wood has contributed two previous articles to FILM COMMENT in the past year; and is the author of several books. His work was reviewed in FILM COMMENT’s “Critics” section, last issue. He teaches film at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario.