Moebius Dragstrip

Monte Hellman makes Westerns. He’s made them again and again. He’s made them in Utah and he’s made them in Europe; he’s made them with horses and he’s made them with hot rods. He’s made them with Sam Peckinpah and he’s made them with Samuel Beckett. Famously, in the space of six weeks in the summer of 1966, he went into the desert with a small crew and a little of Roger Corman’s money, and made two.

They didn’t set out to be psychedelic, those two Westerns—The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind—but they wrenched the skullcap off the form anyway, rearranged the tumbleweeds, left only what mattered. They stripped down a genre that had already been desiccated and gussied up and burned to the ground a hundred times over; stripped it down and rebuilt it from scratch, remade it in a thoroughly modem, thoroughly ancient way—remade it so that the trail became a loop. So that every lonely rider could come around every lonely bend and find himself already there. Doubling up, doubling back, seeing double, two at a time: for Hellman and his regulars it was both a way of doing business and a way of making sense. Jack Nicholson performed in and co-produced both of those Westerns; wrote one of them himself. That was the business of it. Warren Oates stars in The Shooting—twice, as things tum out: two sides of someone named “Coin.” That was the sense of it; cutting a comer and finding yourself already there.

It was, in part, a tradition that Hellman seemed bound to uphold. In 1956, Roger Corman went to Hawaii and directed two films back-to-back, She Gods of Shark Reef and Naked Paradise, later retitled Thunder Over Hawaii. (He made six other films that same year.) In 1960, Corman went to Puerto Rico, directed two films, The Last Woman on Earth and The Creature from the Haunted Sea, and produced a third, Battle of Blood Island—within the space of five weeks. That same year, Corman went to South Dakota, directed Ski Troop Attack (featuring local ski teams from Deadwood and Lead high schools: “They turned a white hell red with enemy blood!”), and produced a loose retooling of Naked Paradise entitled Beast from Haunted Cave. This last film Corman entrusted to first-time director Monte Hellman. Hellman (born Himmelbaum, 1932) spent much of the early Sixties as one of Hollywood’s intellectual fringe-dwellers, floating in and out of Jeff Corey’s acting classes (where he’d meet Nicholson) and parlaying a background in drama at Stanford into a $55-a-week job sweeping out the film vaults at ABC. Occasionally he’d do some pickup work for Corman, shooting additional scenes for The Last Woman on Earth and The Terror.

It was a hand-to-mouth kind of time, as Corman would eventually recall: “A lot of people look at these films today and ask me if I was being existential. No. I was primarily aware that I was in trouble. I was shooting with hardly any money and less time.” “How’d I get involved with Roger Corman?” Hellman later echoed back to an interviewer. “Well, Roger lost $500 he invested in a stage version I did of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, so I thought I’d better pay him back by doing some films for him. Eventually, we made some Westerns, which was a bit of a full circle for us, because I’d staged Godot as a Western, too. Pozzo was a Texas rancher and Lucky was an Indian. I think I see a lot of things in terms of circles and circling back. It just seems that’s what so much of human endeavor is.”

At the time, though, that existential circle may have seemed a little looser; a little less like a noose, a little more like a hula hoop. Opening on the bottom of a double bill with Colman’s The Wasp Woman, Beast from Haunted Cave—in which a giant-sized, cheapo-Cubist arachnid begins abducting women in answer to some ur-biological need—was, as Hellman fondly tells interested parties, his version of Key Largo… “but with a monster added.”

Hellman has tried everything, tried it twice. In 1991 an article appeared in The Village Voice, anticipating—perhaps in the slow, lolling wake of the director’s strange, estranged Iguana—some sort of Hellman renaissance; it was titled “Starting over, and over.” The director told the author: “Even if you believe in determinism you’re living an existential life. You’re an existentialist whether you know it or not.”

Hellman was one of the most serious filmmakers of his generation. He wrote scripts with Jack Nicholson years before anyone knew the actor’s name, elicited three of Warren Oates’s finest performances, and directed one of the few American movies about cars and their drivers that really matter: Two Lane Blacktop.

But other things matter, too; things like mistakes and delays, miscalculations and irruptions of the irrational. Hellman directed spaghetti gunslinger Fabio Testi making love to Jenny Agutter under a waterfall, and Guyana: Cult of the Damned‘s Stuart Whitman faking chopsocky alongside A Better Tomorrow‘s Ti Lung, and the killer Santa Claus film, Silent Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out!

He hasn’t finished a film since 1988.

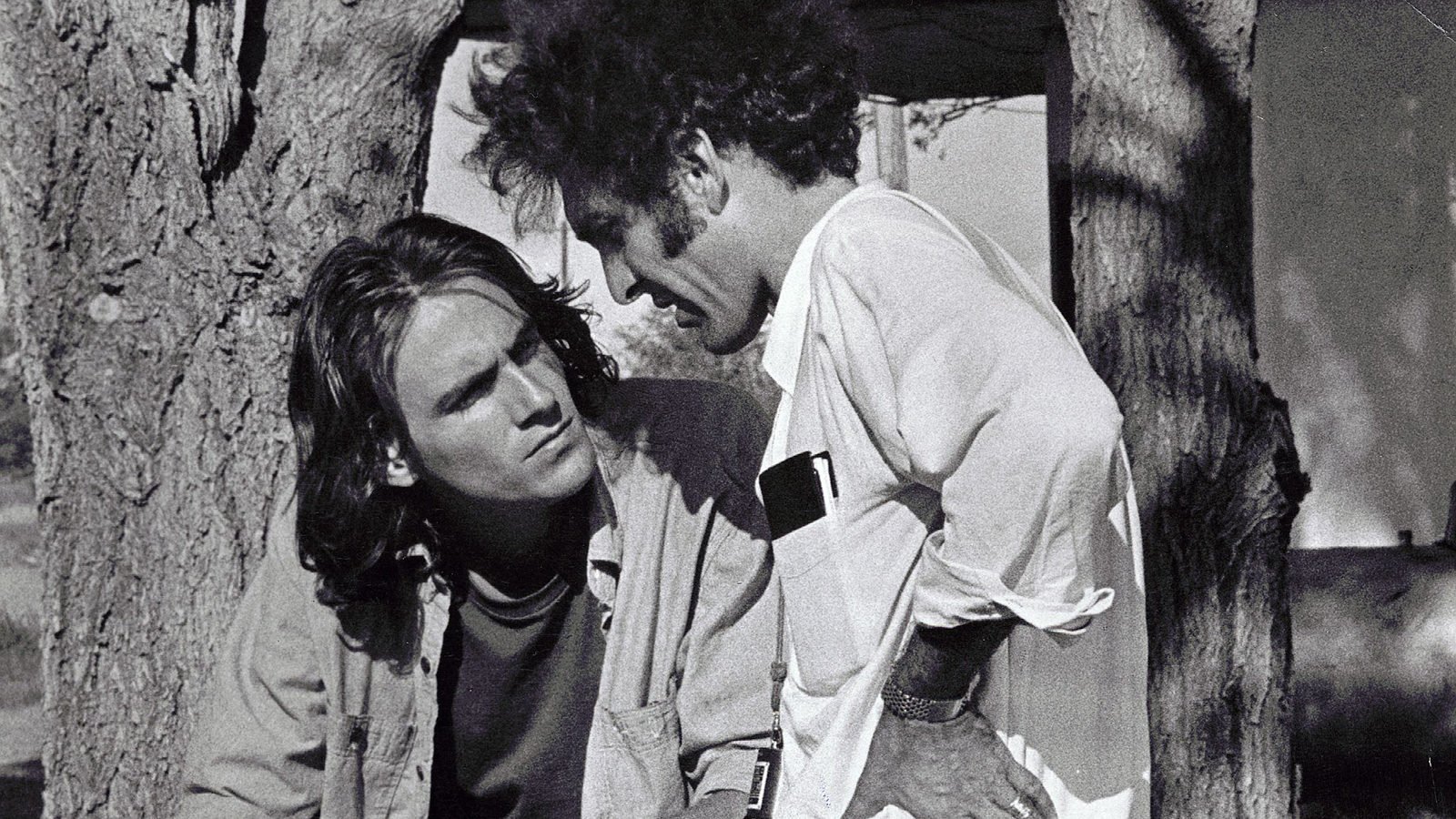

Jack Nicholson and John Hackett in Back Door To Hell (Monte Hellman, 1964)

Circling the Wagons

The first shot of The Shooting is a shot of a horse—a reaction shot. It is 1966, and Lancelot du Lac is still eight years away, but a circle is already emerging. (“Watch carefully Lancelot,” wrote Chris Marker, once upon a time, “and Roger Corman’s The Red Baron. They tell the same story.”)

A sign reader, Willet Gashade (Warren Oates), returns to his camp, followed by someone. He makes it easy for them, leaves them a trail.

At the camp waits Coley (Will Hutchins), a sagebrush nayf with a piece of bad news: Leland Drum, a fellow camp-dweller, has been shot dead, and Coin, the group’s fourth wheel, has ridden off into the desert. (Throughout the film, a fourth figure keeps adding in and subtracting out from parties of three.)

From Coley’s understanding, Drum and Coin had, in Gashade’s absence, ridden “into town” and perhaps been a party to an incident: someone “rode down a man and a little person,” Coley says Leland said, “maybe it was a child.” Upon their return to camp, Drum and Coin had an argument, and Coin left. A little later, seated by the fire in the dark of night, Leland is fired upon, his face blown off by an unseen assailant.

Gashade’s mind becomes “all unsettled” at the telling of it; then he gazes into the wind and announces, “Something’s coming.” A shot rings out, a crow caws murder from the sky; Coley kabuki-skedaddles across the frame, dusting his face and his footsteps with white flour from a flapping sack—a stage effect only one of Godot’s muddled minions, or Thomas Pynchon’s shanty-singing plebes, could so blithely perform.

Along the rise surrounding the camp, a figure appears: “It’s a Woman!”

Perhaps her name is Destiny (it was in Flight to Fury)—we’ll never know. For us, she is a mud-speckled Millie Perkins, once the embodiment of Anne Frank, now so coiled and venal she might be Kim Darby’s True Grit adolescent grown into a Dodge City dominatrix. And she has a proposal: a thousand dollars to be shown the way to Kingsley—across the desert, in the direction Coin had taken.

The three set off: Coley smitten with the Woman, who remains contemptuous of everything, while Gashade glares and figures, all unsettled, certain that the end of the trail won’t be a pleasant one. Every now and then a nonexistent line is drawn, shots are fired into the vast nothingness, and perspectives are exchanged:

“I don’t see no point to it,” Gashade exclaims.

“There isn’t any,” the Woman explains.

And that’s it, pretty much—except for Jack Nicholson. Trussed inside a leather ensemble—vest, tethers, riding gloves—too tight for a tiny toreador, and introduced with a closeup of his beady, Karen Black eyes so cut-to-shock that it might have been torn from a Jack Kirby comic book, comes Nicholson’s lightning-draw gunfighter, one Billy Spears. “I’m gonna blow your face off,” he says to Coley, by way of how do you do. Is he the Woman’s lover? No one seems to know.

Eventually, everybody chases everybody, faces them down, loses face—or finds a new one. Masks are worn—white flour, trail soot, pulped meat—or torn away, revealing features altogether like the ones we’ve seen before. Billy Spears shares the mutilation Jimmy Stewart once suffered in The Man from Laramie, and Gashade finds Coin, finds himself, finds time slowing down, film slowing down, everything melting into everything until the point is made: there isn’t any.

Carole Eastman wrote The Shooting under the name Adrien Joyce (as she’d do for Five Easy Pieces), and she claimed that its climax was altogether topical: The Shooting was the first Zapruder-ized, quantum Western—the convulsive violence at the end of trail analyzed until it atomized, scrutinized until it scrambled, all meaning left bleeding while the dust blows forward and the dust blows back. Only Nicholson walks away, at last the dandy, horribly damaged, staggering into the sun—or the hot lamps of fame. It was still only 1966.

For The Shooting, the script was “the star,” whittled free of bark, slick as soap, no single meaning allowed purchase, no allegory left unwhispered. Names hang heavy with portent: “Willet Gashade” is a moniker Nabokov might have dreamt, its constituents breaking one way into Nietzschean determination, the other into the elements, where sunlight, or a vapor from Hell, might tear holes in a soothing shadow.

That Oates plays the part from the handle outwards, half seasoned assertions and forward thrust, half stuck in a befuddled fog, makes his an indelible performance: he seems forever to sense the clouds before they accumulate, but never musters sense enough to get inside before the rain. He’s paid to read sign, follow trails, but as he tells someone in another Hellman Western, “You ought to see what I’m picking up on the road: one fantasy after another.”

Three days later, the cast (minus Oates, plus Cameron Mitchell) and crew were at it again. This time, Nicholson was the writer—and the star. Ride in the Whirlwind was born from memories of Vittorio De Seta’s 1961 Bandits of Orgosolo and fueled with fronti er patter Nicholson cadged from a collection of cowpoke diaries written a hundred years before, entitled Bandits of the Plains. It’s an oater with an old, old odor and a hitch at the end; Nicholson claimed it all went back to Camus’s “Myth of Sisyphus.”

The dialogue is as simple and specific, as naturalized and archaic as the predicament presented: Three innocent cowpokes inadvertently bed down beside the encampment of a group of murdering stage-robbers. In the morning, vigilantes arrive. A shack burns down; human fruit hangs from a tree. One of the cowpokes and all of the bandits are killed in the siege; the other two, Nicholson and Mitchell, light out to save their lives.

Along the way, there’s time for checkers; time for an appearance by Millie Perkins, an extended sketch regarding the way men tend to confuse abduction and seduction; time for carbuncles and martingales. Time enough for a man named Adam to fall on his knife.

The Shooting was the first film Hellman made with Warren Oates. “Warren was a poet,” Hellman remembers, “but I never knew it until he died.”

Ride in the Whirlwind was the last of four films Hellman made with Jack Nicholson. “The result,” to borrow what Phil Hardy would write years later, regarding Five Easy Pieces, “is less a story and more a collection of incidents and character studies, all of which inform each other and extend our understanding of Nicholson’s mode of survival: flight.” It was still only 1966.

Harry Dean Stanton in Ride the Whirlwind (Monte Hellman, 1966)

Flight

In 1964, Hellman and Nicholson went to the Philippines for a few weeks and, Corman-style, finished Back Door to Hell and Flight to Fury; Nicholson wrote the latter, cos tars in both.

Murder, resignation to imminent death, hysterical nihilism—all of these and Beaver Falls, Idaho; that’s what Back Door to Hell and Flight to Fury have to offer, and I’m only talking about Nicholson’s incarnations. A vacant grunt on a no-exit mission in the former, filmed first, he’s given to vacillations between E.C. Comics-esque, Shocking War! banter (referring to his partner as “Sgt. Blood” and “Sgt. Courage”), and gazing across a room filled with uncomfortable Filipino bar girls and admitting: “I don’t even know if I feel like feeling anything.”

In the latter, he’s a psycho who walks through hell—Macao casinos; a plane wreck; raping, murdering banditos—in a pair of gradually filthier white bucks and a shit-eating, death’s-head grin. The young actor meant it as a parody of his earliest work, The Cry-Baby Killer. “Nobody’s gonna just put a name to me and that’s it,” Nicholson would later assert, in Ride in the Whirlwind.

Flight to Fury begins on a rickshaw driver’s back, the wiry man running and padding, padding and running like Sisyphus, or like the rickshaw driver in Alain Robbe-Grillet’s La Maison des Rendezvous—a novel, set in a Hong Kong whorehouse, Hellman long planned, but never managed, exactly, to film.

“You know anything about death?” Nicholson asks a girl next to him on the plane, minutes before her demise. “Punctuation… that’s all it is.”

“You’re concentrating on the punctuation and forgetting about the sentence,” she says.

Hellman later described Flight to Fury as his Beat the Devil. Back Door to Hell opened bottom-billed to Hush… Hush Sweet Charlotte; it was filmed with the cooperation of the Philippine Department of National Defense. Both films end, numbingly, by the water.

When they returned from the Philippines, Hellman recalls, “Nicholson and I were ready to do a film for Corman that Jack was writing, called Epitaph. Jack and Millie Perkins were going to star; Jack’s character was a young actor, and the story was about trying to raise money for an abortion—a totally taboo subject at the time. The plan was to use footage of Nicholson from the various television shows and movies he’d made up to that point. Corman had agreed to finance it, but when we got back from the Philippines he’d changed his mind and decided that the subject of abortion was’too European.’

“‘But what about a Western?’ he said.’What about two Westerns?'”

The Shooting (Monte Hellman, 1966)

A road is a road is a road

In 1971, Monte Hellman finished only one film: a Western called Two Lane Blacktop. There’s a horse in it somewhere. The Sixties were over, and watching the film it’s difficult to imagine Hellman, who was 39 years old at the time, having ever worn a flower in his hair.

Two Lane Blacktop stars Warren Oates and Laurie Bird, along with singer-songwriter James Taylor and Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson. There are aficionados of both that insist the lank, untucked body temperaments of Robert Bresson’s The Devil Probably find their origin in Two Lane Blacktop. No flowers, just hair.

“You all wouldn’t be hippies, would you?,” Alan Vint wants to know.

“No sir,” Oates tells him, “these are hometown boys—we’re a big family but we know how to keep it together, you know what I mean?”

Two Lane Blacktop found its origin as a script by Will Corry. “It was a rehashing of a lot of Disney-type Fred MacMurray movies,” Hellman recalled, “four kids in a convertible racing this Chevy, and the mechanic falls in love with the girl who has a little VW Bug, and she’s chasing them across the country, and he’s dropping his rags out the window to let her know where they are.”

The film’s screenwriter, Rudy Wurlitzer, eventual Buddhist and author of a series of existentio-absurdist novels (Nog, Flats, Quake), claimed he never finished reading Corry’s version; tossed it out, bought a stack of hot rod magazines for reference, rebuilt the script from scratch.

From west to the east, the film provides a number of races and off-road excursions. The cars star: “I think we discovered that there were twenty-six different camera angles, in and around The Car,” Hellman calculates. The young people’s parts are also precisely calculated, functional. That is, each is designated by, named for, its function: The Driver (Taylor), The Mechanic (Wilson), The Girl (Bird). “I can do this,” The Girl asselts, failing her driving lesson but remaining tllle to function, nuzzling The Driver, getting under his hood.

Warren Oates’s name is a bit more than his function; his name is his car’s, GTO. He shares names throughout the film: jet pilot, test driver, gambler, location scout for a downhome movie about fast cars. And he has a different-colored cashmere sweater for every persuasion. And an ascot. And a bar in the boot. He is not eternal; if he doesn’t get grounded pretty soon he’s gonna go into orbit. But he’s just gonna hang loose. Oates was 43 years old, and his flat-tire mouth rarely held a friendlier smile.

He gets into a cross-country race with the’55 Chevy, for pink slips. That’s the plot.

Will it help to reassert right here that Two Lane Blacktop is a beautiful film: Gregory Sandor’s stark, Americanarama photography countermanding quite handily the post-Robert Frank grotesqueries so fashionable at the time? Or to revel in its moviemovieness: The “motorboating” projector hum that runs under the opening credits, yellow lines ruddering over pavement like damaged sprocket holes or a soundtrack optically strayed? Or the way the projector then quiets down, waits patiently for the film’s elemental apocalypse?

In the meantime, Hellman concentrates on punctuation and forgets about sentence; not interested in topics, the film embraces moods—assertively so. Someone turns on the radio—a news broadcast—in the younger generation’s car, a primer-gray’55 Chevy, and The Driver insists they “turn that shit off; it gets in the way.” He feels like feeling something, but he doesn’t want anybody putting a name to it.

Taylor’s punchably snide and taciturn throughout; Wilson shaggy and disaffected, seemingly in tune only with the “she” that is The Car: “I think I may need to take a look at her rear end.”

“I don’t see anybody paying attention to my rear end,” The Girl pouts.

On the contrary, The Girl’s ultimately car-free ways foul everyone’s emotional plugs, her perpendicularity to the men’s forward motion sending the film’s narrative momentum into a formalist spinout from which it will not recover. The chick just crosses the road to get to the other side, but the film ends in fire.

Esquire magazine, looking for an easy ride, called Two Lane Blacktop “the movie of the year”—before they’d seen it. They were right, but what does it matter what you say about a film? Lew Wasserman, head of Universal, hated it, canceled its advertising budget. It opened July 4th weekend with no ad in The New York Times, and performed like water on a sparkler.

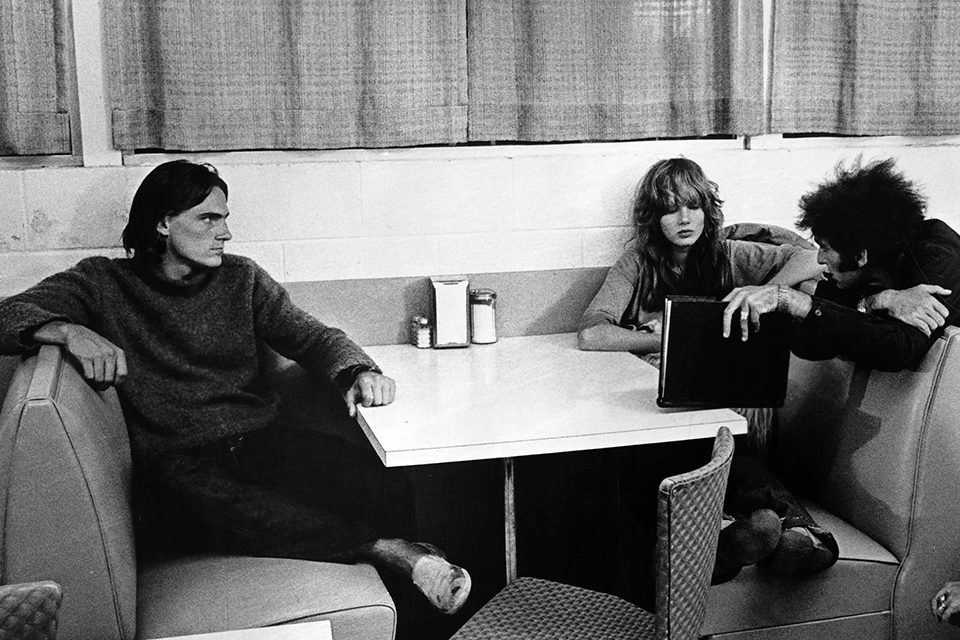

James Taylor, Laurie Bird, and Monte Hellman in Two Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 1971)

The Myths of Sisyphus

“I had been in Europe,” Monte Hellman once told an interviewer, on his way to talking about something else, “and I was preparing a film which didn’t get made… as many of my films don’t.”

Films Monte Hellman was offered, or prepared to make, but didn’t: Fat City (“My biggest regret”); The Last Picture Show (“I was already signed to do Two Lane Blacktop“); Junior Bonner; Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Hellman and Wurlitzer wrote the first version of the script); MacBird (Arthur Kopit’s satire of the Lyndon Johnson presidency).

Films Hellman wasn’t prepared to make, but did: Silent Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out! (“I had absolutely no interest in making that film”); Avalanche Express (which Hellman took over after director Mark Robson died midshoot); The Greatest (which Hellman took over after director Tom Gries died midshoot).

Films on which Hellman worked, but left: Baretta (pilot for Robert Blake TV series: “Blake baited me from my first day on that set, so I quit, even though Elisha Cook Jr., who was a guest star, kept telling me to ‘take the money and run'”); Call Him Mr. Shatter (a Hammer/ Shaw Bros. coproduction starring Stuart Whitman and Ti Lung).

Films Hellman has developed and refers to as “alive and well and living in South Pasadena”: Dark Passion, or is it Red Rain (based on a convict’s prison diary); Secret Warriors (“a Charles McCarey, Cold War story”); Toy Soldiers (about a radiation leak); In a Dream of Passion (the Alain Robbe-Grillet-based project set in a Hong Kong whorehouse); The Last Go-Round (based on something by Ken Kesey).

Films on which Hellman served as unit director: The Big Red One (S. Fuller); RoboCop (P. Verhoeven).

Films on which Hellman served as editor: The Wild Angels (R. Corman); Bus Riley’s Back in Town (H. Hart); Head (B. Rafelson); The Killer Elite (S. Peckinpah); Fighting Mad (J. Demme).

Michael Weldon’s Psychotronic Video Guide asserts that Hellman edited action sequences featuring Harry Dean Stanton into Leone’s Fistful of Dollars for television release. Weldon also asserts that one “Floyd Mutrux” wrote Two Lane Blacktop. Here’s a rock I looked under just because Hellman’s editing credit was on it, and what a yummy-looking treat I found:

Target: Harry, aka How to Make It, directed by Roger Corman; starring Victor Buono, Vic Morrow, Suzanne Pleshette, Charlotte Rampling, and Cesar Romero. Assistant director: Alain (Serie Noire) Comeau.

Hellman: “I’ve always been attracted to the myth of Sisyphus, and I think there’s a little bit of Sisyphus in all my films, the idea of an action that is repeated over and over again. You know, the man who climbs the mountain to push the stone to the top, and the stone rolls down, and he has to start all over, again and again.”

Things still come up, sprouts of rumors of projects: a update of Whirlwind, an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s Hellmaniacal Freaky Deaky.

Warren Oates in Cockfighter (Monte Hellman, 1974)

Handling Birds

In 1974, Monte Hellman finished a film called Cockfighter; it’s a sequel to Two Lane Blacktop, but it’s not a Western. It is the best film to have been made from a novel by Charles Willeford, who once wrote novels set amongst Filipino bar girls. (Though the other two, Miami Blues and The Woman Chaser, have their finer facets: the character- rich equations of Fred Ward, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Charles Napier in the former, the sublime balletics of Patrick Warburton in the latter.)

Cockfighter opens inside a GTO, that is, inside Warren Oates’s name-taking interior: “I learned to fly a plane; lost interest in it. Water-skiing, lost interest in it…. ” Oates is still smiling, but something else has crept in. Now he’s a Melhorne handler named Frank Mansfield, a man who’s been known to talk too much and is currently holding his tongue. “Anything that can fight to the death and not utter a sound… well…,” someone says, and you know who he’s talking about. Right at the beginning, Frank loses his girlfriend, Laurie Bird, in a bet, to Harry Dean Stanton, the cowhand who’d put the moves on GTO three years before.

Hold the title of the film in your hand a minute. It’s weighted like a sap. It feels more like a topic, less like a mood. In the course of things, one man shoves his finger up a rooster’s ass, several men are robbed of their pants, and one proposes a drink to “the mystic realm of the great cock.” And just like that, the film is loose, shambling, digressive, altogether affable, helped not a little by Nestor Almendros’s photography (an expressive departure from Sandor’s clean lines, a return to the L.A. funk of Flight to Fury), and Michael Franks’s Van Dyke Parks-y score.

It is, amidst scenes of difficult-to-take bantam violence, Hellman’s gentlest, most embraceable, most feminine film; it ends coolly, even joyously, in the trees. But it’s also quite vigilant in its thematic dishevelment. At the climax, Oates tears the head off his cock and gives it to his estranged girlfriend, Mary Elizabeth (Rebecca Pearsey), who puts it in her purse and departs in anger. Frank “then sallies off, arm-in-arm with his partner, Omar (Richard B. Shull), having just won the “cockfighter of the year” award. “She loves me,” Frank says to Omar, breaking at last his silence.

What do we have here? A living affirmation of men among men? A two-lane testament to gendered dead ends? Corman didn’t know either. New World distributed the film as Born to Kill, for which Joe Dante edited in some car chases from Night Call Nurses. It has also been known as Gamblin’ Man, and as Wild Drifter. The box for the Born to Kill videotape release reads: “The woods are scary… The people are worse!”

Cockfighter is the second and last film Hellman made with Laurie Bird; she’s last seen in Monteland dressed entirely in coxcomb red, hauled out of the cockfighting pit slung over Harry Dean Stanton’s shoulder. In two rums, she made more of an impression, left more of a synaesthetic presence, than many actors do in a career. Look at her hair in Two Lane Blacktop, the way a little sweat and a little wind and few days sleeping in the back of a car culminate in the odor of an era; behold Laurie Bird’s bell-bottom ass and frumpled eyes, her moccasins and her serape, her petulant voice—you can smell the Sixties still on her.

Only it wasn’t the Sixties anymore, and it never would be again.

Lobby Card for The Beast From Haunted Cave (Monte Hellman, 1959)

Hong Kong Whorehouse

“They asked me to direct a scene in what I considered to be a racist way, so I quit,” Hellman recalls of (Call Him Mr.) Shatter, a Hammer/ Shaw Bros. coproduction, shot in Hong Kong, that may have been close as the director ever got to the inside of Robbe-Grillet’s maison. It is more or less awful: Whitman some sort of world-weary punisher, sidesaddle with Ti Lung, stripped to the waist, two years after Bruce Lee had died.

Michael Carreras gets the directing credit, but Monte gets the memories. On the commentary track of Two Lane Blacktop‘s laserdisc release, you can hear Hellman snorting loudly as the trailer announces “the most ferocious martial arts thriller of them all.” Asked how he felt, knowing that Shatter was about to be reissued, “fully restored,” to laserdisc, Hellman replied, “It makes me question the validity of the entire medium.”

All Stuart Whitman remembers is working with “these little Chinese people—I didn’t want to hurt them,” and something about one of Hellman’s girlfriends, now dead, and something about a screening of the film at Hugh Hefner’s mansion. Tactless, Clummy, but you can see what it might have been, maybe: “The leading character in La Maison de rendezvous, although he’s called Sir Ralph, is also known as The American. He’s really Humphrey Bogart in Hong Kong,” explained Hellman once, pondering moves, West to East.

All one can really sense from the film is the why? of something, then the bitter termination of something. “In a low-budget film like this, what things are you aiming for? ” the laserdisc producer wants to know.

“What you’re aiming for,” the director informs him, “is to live through the experience. And there’s the great sense that you’re not going to make it.”

The Last Woman on Earth

In 1978, Monte Hellman finished a film called China 9/Liberty 37. It starred Warren Oates, Jenny Agutter, and Fabio Testi, and in case you’re wondering whether or not it’s a Western, know only that Sam Peckinpah shows up, as a frontier tabloidist, long enough to murmur the lines, “I take the West to the East.” All the way to the East: the film was shot in Spain, with Italian money. In Italy, it’s sometimes known as Love, Bullets and Frenzy.

The videotape of China 9/Liberty 37 sold by Video Search of Miami is marketed as “uncut,” largely on the basis of its multiple nude exposures of Jenny Agutter. (“Remember the nude scene in the lake?” pants VSoM honcho Tom Weisser in his book on spaghetti Westerns.) That videotape, as it turns out, is not uncut. It omits the following line, spoken by Warren Oates: “Women. If they didn’t have cunts, there’d be a bounty on’em.”

The film is an inversion of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, with the younger Testi riding into the young Agutter’s britches and forgetting his job, to kill her husband, Oates, who’s older and bearded and fresh out of fantasies. Testi and Agutter’s nude scenes are nauseatingly gauzy, string-sectioned, a fouled reminder of Laurie Bird’s nude scenes by the lake, now lost from Two Lane Blacktop but partially documented in an ancient issue of Show magazine. (Laurie Bird moved to New York, took a bit part in Annie Hall, died of a Valium overdose in 1979.)

Oates glowers grimly throughout, wincing as Italian stuntmen warble “Red River Valley.”

China 9/Liberty 37 just about seethes with hatred, and not all of it directed toward women. At times, it feels like an antidote to Shatter: in the beginning, Testi’s in jail in China (POP. 132), standing in for Monte, waiting to be hanged. “Tomorrow you’ll be a big hunk of dead meat and a little headline,” Testi’s jailer, who you wish was R.G. Armstrong, says. “Better than a big bag of shit every day,” Testi smiles—testifying on behalf of Monte’s free-falling career?

But, like Hellman’s career, things don’t end in China—they move toward liberty, toward cocaine and circuses, toward whores used as shields and brothers raping sisters, toward a final burning frame. Beyond sexuality and into psychosis, as in the joke Testi teaches Agutter when he teaches her to stay with Oates, teaches her to show him her nuts.

It’s a rough road from China to Liberty, but everyone struggles to live and forgive. Sometimes they don’t make it. Hellman dedicated the film to his father, and he named his dogs after those two destinations.

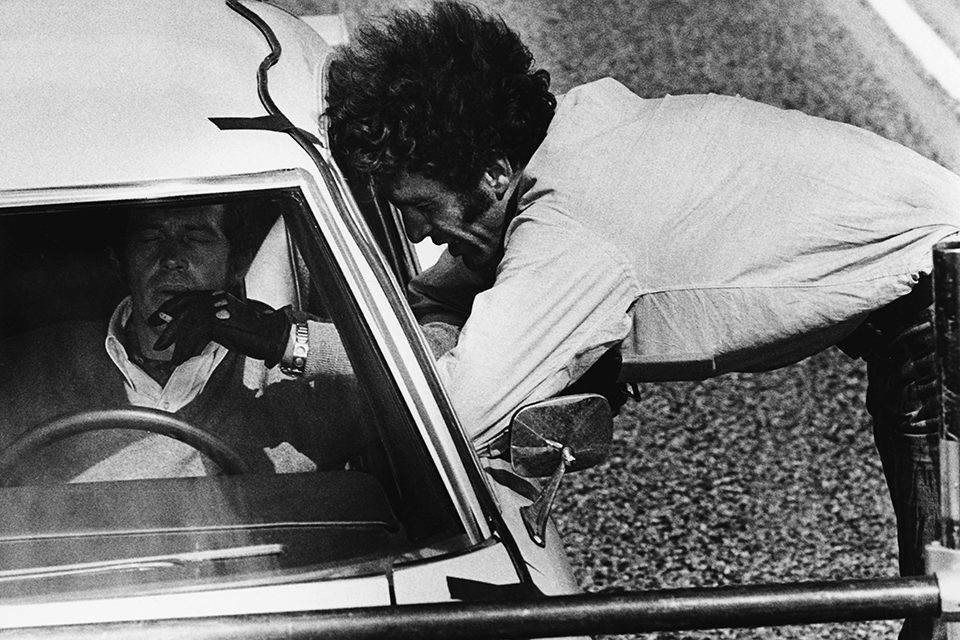

Warren Oates and Monte Hellman on the set of Two Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 1971)

He-God of Shark Reef

“He’s back to the Beast from Haunted Cave,” someone quipped to me at the American Cinematheque in 1996, recalling Hellman’s 1959 directorial debut, after a screening of 1988’s Iguana—in which a cheapo-Cubist lizard-man abducts a woman in answer to some biological and ur-sociological need. It’s the last film Hellman made for which he feels any genuine regard; its dedication reads, “For Warren”—presumably the same Warren who drove out of Two Lane Blacktop, looking for a set of emotions that would stay with him.

Everett McGill—the titular reptilian—already has a set; a face like a svelte Ben Grimm, bumps, boils, swirls, scales, and emotions to match: he’s declared war against mankind. Surely Hellman’s admitted it somewhere: the film’s a remake of Carol Reed’s Outcast of the Islands.

It was made with Italian and Spanish resources, and “the participation of Fabio Testi,” which means the Italian cos tars; cos tars in a way that reminds me of Franco Nero in Fassbinder’s Querelle, maybe because Iguana might well have been called Queequeg Overboard.

McGill, the iguana, his name is Oberlus; he was a harpooner on a vessel called The Old Lady (hold that in your hand a minute), but he lowers himself into the sea and sets out to become the King of Hood Island. He builds his kingdom by enslaving castaways who happen to land upon his rock. Men first, kept in line by a series of castrations, and finally a woman; a Woman, not a Girl, not Destiny, but a monster in proportion to Oberlus—a sexual virago who prefers anything to indiffere nce, and who, once raped by the King, fucks him to death.

Her name is Carmen (Maru Valdivielso)—it was Catherine in China 9/Liberty 37—and she repeatedly demands, of every man who beds her, her sexual freedom from the slavery of submission. She embraces the anarchy of individual desire, and her anarchy undoes Oberlus’s tyranny. And there you have Monte’s films: men, imprisoned by hideous flesh, lusting for nihilism, sideswiped by women they meant to possess. With a little Roger Corman thrown in: a cheaply executed beheading (Robert Ryan’s son Tim), a quick trip to the haunted prop shop, a fistful of makeup that won’t exactly stay put.

Iguana‘s about finding a ruthless, even altogether alienating code of behavior, and sticking to it. The only film Hellman’s directed since is one in which Santa Claus is an axe murderer: Silent Night, Deadly Night 3, a genre flick in which the blind lead the bland. There is no hero in it, save Monte, but there is a sightless heroine, a slasher with an exposed brain, and bit of cockfighting rapport between Robert Culp and Richard Beymer. It’s funny in parts, and sad in parts, but it mainly suggests that, pace Kenneth Anger, the gift of filmmaking is sometimes placed beneath a burning Christmas tree.

Both Iguana and the Santa Claus film end floating on lullabies, lost among crags where women and their complications find no purchase, and where men are only free enough to fly into fury, drink to their cocks, and wander off who knows where. Warren Oates was the only warm spot on Hellman’s battle-scarred planet, and once he was dead, everything else was cast adrift on a churning, spleen-darkened sea.

Epitaph

“I realized my hero had become miserable, stubborn, and out of touch,” Vincent Gallo complained of Monte Hellman, ten years later, in the summer of 1998, upon the abortion of a collaboration. It wasn’t 1966 anymore, but Monte Hellman was holding firm. A man and a little person, maybe it was a child. In Gallo’s puny circle of words hides the highest praise.