See What I Mean?

In a running gag in Bong Joon Ho’s Okja, a Korean-American member of the Animal Liberation Front played by Steven Yeun tattoos “Translations are Sacred” on his arm. His boss, Jay (Paul Dano), has violently reprimanded him for selfishly mistranslating the wishes of the film’s young heroine—a joke topped by the tattoo’s own distortion of Jay’s original complaint, “Translating is sacred!” Last January, with the Golden Globe for Parasite in his hand, Bong gently nudged audiences in his acceptance speech: “Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.” In light of our truly international film culture, we give voice to a key mediator in cross-cultural film dialogue: the subtitler. Seoul-based Darcy Paquet has subtitled films for Hong Sangsoo, Park Chan-wook, and Bong (including Parasite), in addition to working as a film critic and journalist.—Manu Yáñez Murillo

Read Manu Yáñez Murillo’s interview with Andrew Litvak, subtitler for Jean-Luc Godard and Claire Denis.

By working as a journalist and writing about Korean cinema, I got to know distributors and people at the international sales departments. Sometimes they had a subtitle that they weren’t happy with, and would ask me to fix it. The first co-translation I did—with my wife Yeon Hyeon-sook—was actually of Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder (2003). I did several subtitles but then I stopped for a while, and in 2014 started again. By that time my Korean had improved, so I began doing the rough drafts on my own. Thanks to Korean cinema’s particular landscape, I’ve been able to go back and forth between mainstream features and low-budget films, though the work is very different. In Korean commercial films you can feel there’s an effort to clarify many things in the dialogue in terms of socio-political or historical context, while in most independent films there’s a lot more suggestion. So actually I enjoy translating independent films more.

The Handmaiden

Most people assume that when I do subtitles, I watch the film completely before even starting the work, but I don’t. I try to watch every film three times. The first time, I’m watching and translating at the same time. It takes me four or five days to get through the film, which is a really unusual way to watch a movie. But there are two things I like about this: one is that I prefer to translate as I’m experiencing each scene for the first time. And the other thing is that subtitling is such hard work that I like being pulled along by the narrative, wanting to see the end of the film. After I finish, I go back to the beginning and I go through the film once or twice more. That’s when I can think about the whole structure of the film. If there’s something that is first mentioned at the beginning and then echoed later, I make sure that that relationship works in the subtitles.

One of the main differences between writing subtitles and translating a novel is that a novel translation replaces the original, but when you’re watching a film with subtitles, you can hear the actor’s voice and see his expression—a lot of the emotion of the original dialogue is transmitted even if the audience can’t understand the words. So the subtitles should match the emotions the film evokes, or the audience feels a gap. This is particularly complex with comedies. The way a sentence is structured affects the humor. At festival screenings of Korean films attended by non-Korean audiences, I’ve noticed that the audience doesn’t laugh when they read a punch line but at the moment that the actor delivers it. They can sense a release of tension in the actor’s voice and then everybody laughs. So ideally I try to put the punch line in the same part of the sentence where it falls in Korean. The problem is that sometimes the word order is very different in Korean.

Parasite

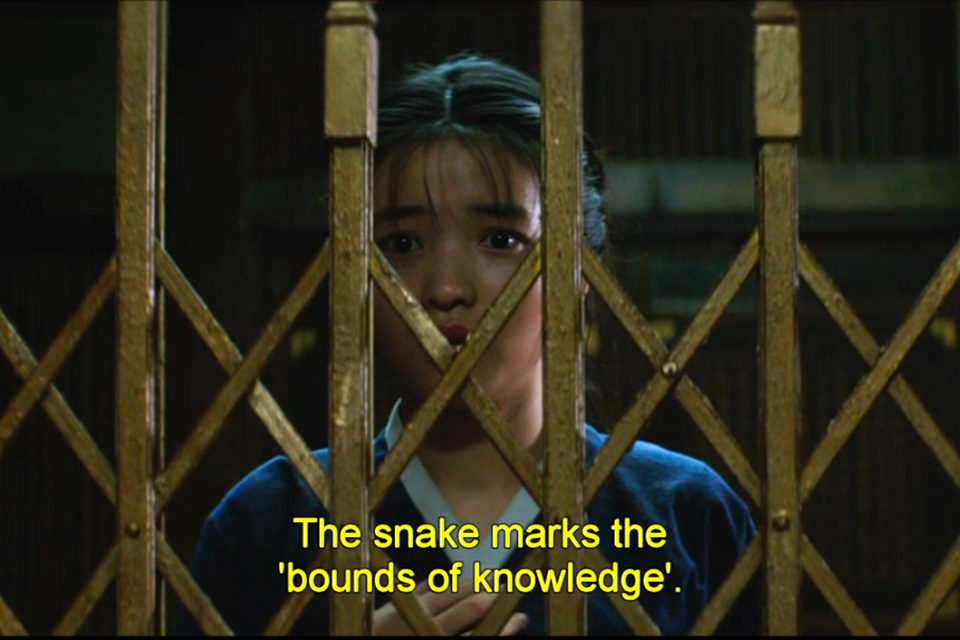

The most interesting subtitling experiences come through collaborative efforts with the film’s authors. That was the case with Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden (2016). When I was assigned to do the English subtitles, I was asked to get an e-book copy of Sarah Waters’s Fingersmith—the novel on which the movie is based—so that I could search for particular lines of dialogue. So basically the director was asking me to go back to the original English dialogue to reflect it in the subtitles as closely as possible. But there were some interesting complications, because Park Chan-wook had read the novel in a Korean translation. In the film, when the character of the handmaiden goes into her master’s library, she sees a sculpture of a snake at the door, and a man says, “That snake marks the bounds of innocence.” In the novel, there wasn’t a snake—it was a hand pointing up with a finger. While doing the subtitles’ final check, the director got confused because in the book’s Korean edition, the word “innocence” had been translated in a way that he understood as “ignorance.” Actually we ended up with a third option. I told Park that if we used the term “knowledge,” people would think about the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden. In fact I had assumed that the snake represented the serpent in the Garden of Eden, but when I shared my view with the director, he denied the reference. He thought about all this for a long time, and he finally decided to use “knowledge.” So there’s a reference to the Bible that exists in the English subtitles that is not in the original Korean film.

With Bong Joon Ho, I’d say his dialogue translates very well into English. To Koreans it doesn’t sound as strange as Park Chan-wook’s, which tends to feel a little bit foreign. Bong’s dialogue feels more natural, and yet it’s very creative and memorable. For the most part, when translating Bong’s films, you can stay very close to the original and often achieve the same effect in English that he gets in Korean. He understands very well the audience’s perspective, even of viewers who don’t speak Korean. And from the very beginning of my collaboration with him, he was willing to be flexible in the translation. In Mother (2009), for example, there’s a character who doesn’t appear on screen very often and yet is very important in the plot. His name, Jong-pal, has a particular, memorable feeling in Korean. The audience needs to remember this name, because throughout the film other characters talk about him. So instead of translating his name as Jong-pal, Bong had the idea to name him “Crazy JP” in the subtitles. The character is kind of crazy, so it fits his personality, and with that name the foreign audience remembers the character instantly. We had a similar thing in Parasite, where we needed the audience to remember the name of the son’s friend, the one that goes to study abroad. In this case, we decided to translate his two-syllable Korean name, Min-hyuk, into a one-syllable name, just Min, while with all the other characters we kept their original two-syllable names.

Right Now, Wrong Then

Before I started translating Parasite, I received a very long email from Bong, where he mentioned all the issues that he anticipated we would have to deal with in the subtitles. So, for instance, in the case of the rich family’s husband, the director said he should sound on the whole very educated and gentle, but occasionally somewhat more vulgar. There was this duality to him, the suggestion that he was giving a very soft, elegant appearance on the outside, but on the inside there was something a bit sharper. When he’s with his wife, that side of him really comes out—in his speech especially. And then there’s the recurrent use of the word “metaphorical.” In translating the Korean word you could use “symbolical” or “metaphorical,” but because of the way it fit within the entire movie, we needed to choose one translation and stay faithful to it all along.

With Hong Sangsoo, I did the subtitles for Right Now, Wrong Then (2015), and I’ve done every film of his since. He studied in the United States and speaks English very well, so he knows when a translation feels right emotionally. We work differently because of that. I do a first draft, and then I go to his office at the university, and we watch the movie together. If there’s a particular translation where he feels the emphasis should be different, I just throw around five possible translations at him, and he chooses the one he wants to keep. It feels like a partnership—I should credit him as co-subtitler. His dialogue feels very distinctive in Korean, even though it’s very conversational. A character may say something like “oh, that’s beautiful” or “oh, that’s so nice,” but people don’t use those kinds of phrases in real conversations. He prefers to use simple language, and yet his dialogue is full of complex role-playing. His dialogue is meant to hint at some things without saying them explicitly, so often we have to find the right level—suggesting something without confirming it.

As told to Manu Yáñez Murillo

Manu Yáñez Murillo is a film critic and journalist, and has written for Fotogramas, Rockdelux, Ara, and Otros Cines Europa. He is the editor of the anthology La mirada americana: 50 años de Film Comment.