Locarno 2015: Wandering Voices

Movie theaters played host to video art at this year’s Locarno Film Festival as part of “Wandering Voices,” a new section programmed in collaboration with Art Basel (currently having its annual U.S. show in Miami). At times it seemed odd to be watching such works on a cinema screen rather than a Hantarex monitor placed on a plinth in some white cube setting. Yet the experiment was in keeping with the festival’s reputation for fostering unconventional forms of cinema, wherever they might come from.

It, Heat, Hit

“Wandering Voices” entertains the idea that the moving image should question the boundaries of literal signification. If this is a cherished concept in the art world, it tends to be less so in the world of traditional narrative cinema. At Locarno, a program of five short films suggested a conversation between emergent works and milestones of video art. John Smith’s masterpiece The Girl Chewing Gum (76) was paired with Karolin Meunier’s Anfangsszene, while Melanie Manchot’s Twelve and Shirin Neshat’s Turbulent (98) served as closing pieces. The opening selection, Laure Prouvost’s It, Heat, Hit (10), functioned as a loose introduction to the themes of the program.

Prouvost’s film urges the spectator to leave the room within minutes, disrupting the narrative pact conventionally made between storyteller and listener. And from the tongue-twister title on, the work plays with language as much as it does with images. The short intermingles brief intertitles with quick close-ups—of body parts, food, rocks, fire—accompanied by written words drawn from both the images and the female narrator’s softly intoned voiceover about her childhood memories and personal observations. As we struggle to put together a story of our own, the artist amusingly opposes our intent and, without notice, abruptly interrupts her vague accounts. Resembling videos from the art-folk ensemble The Books, It, Heat, Hit only accelerates its pace as the end approaches, with a countdown announced in a humorous, rather anxious, voiceover. Unsure whether to follow the images or the spoken words, we don’t know what to expect next.

The Girl Chewing Gum

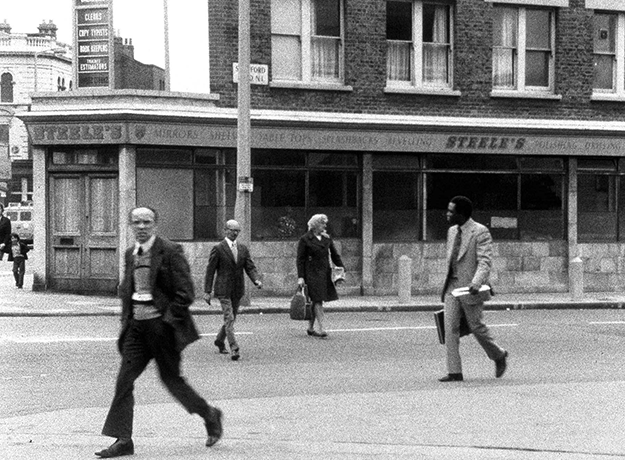

Prouvost’s work was followed by John Smith’s The Girl Chewing Gum, which employs the same playful approach to image/sound disjunction. The film is set on a busy East London corner; the conceit is that Smith is directing the scene framed on screen. We hear Smith, on voiceover, instructing pedestrians to move, addressing cars and pigeons with the same tone he uses for people. The plot twists as fractures are generated between the voiceover and footage: the narrator doesn’t only direct inanimate objects and animals but also denounces a thief who has just robbed the bank. Direct sound and voiceover clash when a piercing burglary alarm goes off. As yet another coincidence of fiction and reality is made obvious to the viewer, we become aware of the artificial nature of the short and of the film medium generally.

In Anfangsszene, Karolin Meunier elaborates on the contrast between performance and reality. A young actress talks about her acting experiences in the presence of a casting director, who’s always off screen (and may in fact be Meunier). Thanks to certain repetitions and instructions given to the actress, we start to wonder whether the scene has actually been scripted. Our preconceptions about nonfiction and staging formats produce a puzzling atmosphere, but such confusion is amusing because the viewer becomes a crucial part of the cinematic game. As with Smith’s work, it is as if we are included in the conception of the short and in the interpretation of its final outcome.

Twelve

The final two shorts draw the series to a darker close. Melanie Manchot’s Twelve is a collection of interviews with former addicts from Liverpool. The interviewees recount and perform, in sequence, personal stories of abuse, irresponsible parenthood, and other struggles, letting voiceover and images present two different sets of information. As the protagonists are depicted in different settings, their portraits are interlaced with both literal and abstract representations of the stories they tell. Shadowy interludes between each episode seem to suggest that the healing process is not over. Twelve‘s strong cinematic quality (it quotes from Chantal Akerman, Michael Haneke, Bela Tarr, and Gus Van Sant) and references to social issues provide the link to Turbulent, the classic by Shirin Neshat which concludes the program.

While the “Wandering Voices” series was dominated by female authors, Neshat’s work resists a simplistic discussion centered on gender inequality. Through the form of a split screen, the short shows a male singer (surrounded by a male audience) juxtaposed with a female soloist in a chador. As the man sings a traditional Iranian tune, the female vocalist chants a contemporary composition by Sussan Deyhim in an empty space. Considering that Iranian women are forbidden from solo singing in public, the singing style and the split screen express the contrast and incommunicability of gender in the Iranian society. In comparison to the other Art Basel shorts, her film suggests a single reading to the audience, and displays less experimentation with meta discourse and narrative. Yet the contrast with the four other films in “Wandering Voices” is fruitful and suggests an interesting analogy: gender struggle proceeds through constant negotiations and personal adjustments, just as the spectator navigates the realm of contemporary moving image. Offered as a free choice, joining the conversation becomes a most enjoyable game, not an imposition.