Interview: Jerry Schatzberg

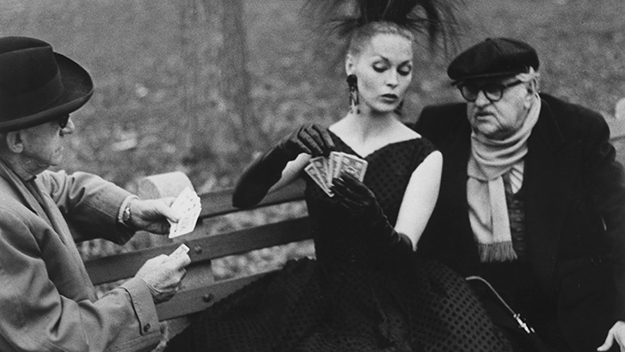

Puzzle of a Downfall Child (Jerry Schatzberg, 1970)

At 91 years old, Jerry Schatzberg has had a storied and frankly Zelig-like career in 20th-century pop culture. Born in the Bronx in 1927, Schatzberg came to a career in photography in his late twenties, soon ascending the ranks to become one of Vogue’s top fashion photographers in an era of peak mid-century glamour. Along with his fashion editorials, he would also befriend and capture iconic snaps of Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, and Edie Sedgwick, among others. In 1970, he made Puzzle of a Downfall Child, a modestly budgeted debut in feature filmmaking starring Faye Dunaway as a troubled fashion model. But it was Schatzberg’s discovery of Al Pacino and the two films he would make with the actor that cemented his place in a burgeoning New Hollywood: The Panic in Needle Park and oddball road movie Scarecrow. Although Schatzberg is often mentioned in association to these two titles, his screen work through the ’70s and ’80s continued to turn up gems, including The Seduction of Joe Tynan and country-music romance Honeysuckle Rose (1980), with Willie Nelson in the central role.

Following a Film Comment Selects screening of Honeysuckle Rose in February, Schatzberg kindly chatted to us about his remarkable career and approach to filmmaking.

You kind of began at this now-mythologized era of American movie culture in the early ’70s. The studio system was starting to fragment. I guess things are always different when you’re living through them, but did you find that there was a new sense of freedom in what you could do and make?

It’s a question that’s always asked, but I don’t think so. I just had a film I wanted to make, and I’d been working on it for a while, and I just went through the process of trying to get it financed. I wasn’t aware there was a movement going on. I just wanted to make a film and wanted to make a certain way, and I found the means to do it.

I was on your website this morning, looking at photos from some of your fashion editorials in the late ’50s and early ’60s. They’re so beautiful. To me, it brings back this bygone Manhattan—both in the working class feel and the contrasting glamour. I wondered how you feel when you look at those photos now, or at the way Manhattan seems to have altered so much since then?

You know, I don’t think of them that way. I don’t think they’ve aged that much. Actual life in New York has changed, of course—hip-hop brought something to the scene that wasn’t there before. I had a couple of discotheques in New York in the ’60s, and the social life was different. And I think as time went on—maybe in the ’70s when Studio 54 became popular, it brought a different set of social values to New York, for good or for bad. By the time that came, I was really getting out of that world and concentrating on films.

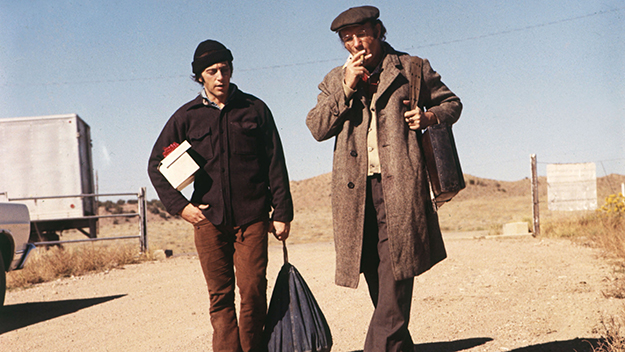

Scarecrow (Jerry Schatzberg, 1973)

You also had censorship breaking down in the U.S. around the time you were making your early films, but then other rules in Europe. I read that The Panic in Needle Park was banned in the U.K.?

Yes, it was banned in the U.K. The Man with the Golden Arm was banned, also. They felt they didn’t want to have films about heroin.

Were you aware at the time of making the film that it would be so shocking to audiences, or that you might have difficulties with the censors?

No, you know. I knew a lot of musicians and people at work that did drugs. That was just part of the life. There were a lot of tragic stories there, and a lot of my friends died of overdoses. So you can’t help but be aware of it.

I read that you first spotted Al Pacino in an off-Broadway play, is that right?

Yep. The Indian Wants the Bronx, an Israel Horovitz play. I was really very impressed. I was with my business manager, and I went along with him because he was trying to sign Al up. His performance was so dynamic, and when I went backstage it was such a pleasure to see he was a real guy, and we got along very well. So when I was offered The Panic in Needle Park, I turned it down actually, because I didn’t think I wanted to do a film about drugs. I had gone through all that. Until my manager signed Al up, and said, there’s a good screenplay out there called The Panic in Needle Park. And I said, well I think I turned that one down. And he said, it’s a really good screenplay. I said I didn’t know if I wanted to get into that world. Living in it is one thing, reproducing it is another. He said, you know Al is interested. And those were the magic words. Then I went back and read the script, thinking of Pacino in that character, and it made all the difference to me.

I read something else I loved, which was that Pacino and Gene Hackman, when you guys did Scarecrow, sort of butted heads with their different approaches to acting.

Most actors are different from one another. But Al, when he gets into a character, he stays in the character, and sometimes it’s annoying, because for someone like Hackman—he goes back out of character and takes off the costume, but Pacino will carry the character around with him for the whole film.

The Seduction of Joe Tynan (Jerry Schatzberg, 1979)

I was thinking about your depiction of women, from Puzzle of a Downfall Child through to The Seduction of Joe Tynan. You really take care to portray what might be just the wife/other woman as fleshed-out, nuanced, psychologically apt roles. You seem very interested in the internal drivers of these women, of women who are a little bit neurotic.

Yes, I’m interested in people involved on the margins. Faye’s character in Puzzle was something I’d seen a lot in fashion photography, people didn’t really care very much about the models or how they felt. And one day they’d say, “Oh, we’ve seen her too much” and that was it, the end of their careers. I thought it was terrible. Actually what stimulated me to want to make a film about it, was that Vogue asked me to do a collection in Paris, and I was very happy and wanted to take my favorite model with me, and they wouldn’t let me. They said no, she’s been seen too much. She was only in her early thirties.

Now they start them even younger, 16 or 17. They’re finished by the time they’re 20. And there’s no regard for their feelings, they’re still young and beautiful and full of ambition.

And what happens when you peak at that age, and you’re looking down the barrel at the rest of your life?

Yes. It destroyed so many of them. I kept friendships with many of them, and they had a difficult time finding work. They’d been treated to first-class everything when they’d been working for the magazines, and when they find a new face, they’re dismissed. And most of them really know how to work. But each generation has a new set of models, the ’80s and ’90s had supermodels, and were well-regarded. The highest-paid model in the ’60s I think was Jean Patchett, and she was paid something like $60 per hour. Which was nothing compared to what they were making in the ’80s and ’90s.

The Panic in Needle Park (Jerry Schatzberg, 1971)

Something that linked a lot of your films in that decade, across very different subject matter—whether it’s Honeysuckle Rose or The Seduction of Joe Tynan—is the real emotional intimacy between people who are on the margins. Why do you think this is something you’ve returned to?

I think the way it happened for me—the first film was something I really wanted do. It took me four years to get it. The Panic in Needle Park came to me, people saw my first film and came to me. I went back to them and apologized after I turned it down one time and then we went back to it. We made a good film, I think. And that’s when I became friendly with Joan Didion and John Dunne, and we actually worked on another film together that didn’t get on for me. But you know I don’t think there’s any universal thinking in things like that. Like, Scorsese always did films at the beginning that were close to his family life, or to growing up. While I was maybe open to other things. I don’t think there are any patterns, we’re just different people.

And I was older than a lot of the guys when I started. I think that gave me a different point of view because I had probably lived a little bit more at that time. When Scarecrow was sent to me, it was because of the other films I’d done. I think I made a mistake after Scarecrow though, because that won a prize in Cannes, and I was immediately offered an office and a salary at Warner Bros., and I took it. I think that was a mistake. I think I should have just sat back and read scripts until I found something I was emotionally or intellectually attracted to. I should have waited. I worked in an office for Warner Bros. in New York for two years and we didn’t end up doing a film.

Though I can see why the offer would be immediately tempting.

Sure. When you’re struggling to get it on and someone offers you that, you get seduced.

Honeysuckle Rose (Jerry Schatzberg, 1980)

Do you think that coming to filmmaking with more experience made you in some ways less likely to want to work through personal stuff, your upbringing, your background, in the way younger filmmakers did starting out?

That’s an interesting theory. I named my production company after Grand Concourse—a highway that runs through the Bronx. I was brought up in the Bronx until I was about 14. And the people I hung out with were Italian, Irish, Russian, Jewish. You learn certain things. We were sort of second-generation immigrants. My parents were both born here, but my grandparents came from different places. We settled in parts of NY that were for immigrants. As you start to work and become successful, you start to assimilate out of those areas. In my photographs, I find I went for something that was a little bit funny or unusual, and I’m getting ready to do a show now in France, and when I look at my photographs I think they’re wonderful to look at. When I think of Grand Concourse, I think it’s a bit like off-Broadway: you don’t have the best of everything, but you strive more to find things that are original and interesting because of that. And maybe that’s what made me go in different directions. I think our upbringing has a lot to do with the sorts of choices we make, especially when coming into something new.

I wanted to ask you a bit about your relationship to film criticism and critics. They have often, I think, misunderstood things you’ve done. But you also have had a wonderful reappraisal of a film like Scarecrow in 2013 when it was restored and re-released. And it won the Grand Prix at Cannes at the time, so clearly there were people around who appreciated it. So what has your feeling been toward film criticism over the years?

You know, in any kind of art, you either luck out and one film they’re attracted to, or… I mean, the critics were not really attracted to Puzzle of a Downfall Child. It wasn’t as commercial as I think they wanted to see. But then when you have a first or second film that’s commercially successful, the critics love to jump on that because it’s easy. They can say, if someone criticizes what they say, they can say look at how financially successful it was. And my films were never really that financially successful. I remember I’d talk to some of them at times. But then at Q&As they’d ask about whether something had made money. The only film that really made any money was The Seduction of Joe Tynan, which for me was a commercial film. Scarecrow has come into profit through the years. But it’s very difficult for films to make money. Even Coppola, I think the only films of his to really make money were The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. And he makes wonderful smaller films. So I think making money has a lot to do with it, and a lot to do with whether someone’s going to come back to you to want to make another film.

As somebody that wasn’t around at that time, there was something that shifted at the end of the ’70s. A lot of talk about how studios became risk-averse and less interested in green-lighting more unusual projects?

Yes, definitely. Easy Rider was a change in the industry. Before that, everyone was making Paint Your Wagon and costing the industry a fortune. They’d lose money. So when Easy Rider came out, the studios all wanted to make that. So that made room for us. My first film only cost about a million dollars, and I really only made low-budget films, basically. Not as low-budget as you can go with independent films, because all my films, especially in the beginning, were studio films. And the fact that I didn’t take on budgets of 5, 6, 7 million was attractive to them. But it didn’t always make money for them. If they didn’t have too much to risk, it was fine. They’d save their big-budget stuff for more commercial directors. People make films for no money and they come out and make fortunes, and that becomes the thing to do. Or vice versa, you know. You try to make a film commercial—I think Scorsese’s early films were more appealing to me because they were low-budget, very personal. When he started to make films for $100 million I didn’t take to them as much. Not that it’s only him, but I use him as an example because he’s been so successful and is still making films.

Watch Jerry Schatzberg’s Q&A with Nicolas Rapold at Film Comment Selects below.

Christina Newland is a writer on film, culture, and boxing, with bylines at Sight & Sound, The Guardian, and others.