Film of the Week: The Look of Silence

The recent trial of 93-year-old former SS guard Oskar Gröning has reanimated long-running debates about justice, reconciliation, and the necessity or usefulness of prosecuting war criminals who have reached advanced old age. Much of the debate around Gröning’s trial has centered on the forgiveness publicly extended to him by Holocaust survivor Eva Kor, who received an embrace and a kiss on the cheek from the old man in court. It’s hard not to think of this while watching Joshua Oppenheimer’s new documentary The Look of Silence, a follow-up—and in some ways a contrasting companion piece—to his much-praised but highly controversial The Act of Killing (12).

In one sequence in The Look of Silence, a young Indonesian man, Adi, confronts an elderly former death squad member about his part in the country’s mass murders of the mid-Sixties. The old man’s daughter is present as her father boasts of his exploits, telling how he took a severed head into a shop to scare its Chinese owners and slit throats while catching the victims’ blood in glasses. The woman listens quietly, then asks Adi to forgive her father. Seemingly on the verge of tears—although Adi’s calm ability to contain his upset is an implicit motif throughout the film—Adi replies: “It’s not your fault that your father is a murderer.” He and the woman embrace, and she says: “Consider him your own father” (though seemingly well intended, you can hardly imagine a less inviting offer). The old man, meanwhile, seems miles away from all this: “It’s getting late,” he says, his apparent obliviousness effectively blocking out any consideration of repentance, and distancing him from the horrifying events he has only just been recounting.

For Adi, it is not forgiveness that is primarily at stake in his confrontations, but revelation. He is an optometrist by trade, and many of his meetings with former killers double as eye tests: one death-squad veteran, after railing at Adi’s pressing questions, asks him to make some reading glasses. The film’s repeated close-ups of eye-testing spectacles are a sustained metaphor for hard-won clarity of vision—enabling these old men to see the truth of their past, matching the clearness of the silent gaze with which Adi scrutinizes them.

The Act of Killing has been criticized as essentially a stunt documentary. It showed former death-squad members, many of them proudly characterizing themselves as gangsters, who took part in the mass murder of real or supposed Communists in Indonesia in 1965-66; over a million people were killed, and their murderers today not only flourish in freedom, but openly boast of their crimes. In The Act of Killing, Oppenheimer gave his subjects rope to hang themselves, encouraging them not only to narrate their actions, but to reenact them in fantasy mode as pastiche movie scenes all the more disturbing for their gruesomely kitsch nature. One argument against the film was that Oppenheimer was complicit with his subjects in allowing them to glorify themselves. But the film’s most extraordinary moment was a startling payoff. Having prided himself on his skill at garroting, one man starts helplessly dry-heaving—a classic example of the body speaking the inner disturbance that conscious words cannot.

Anyone who found The Act of Killing unpalatable because of its apparent complicity with its subjects will find The Look of Silence more acceptable—yet the film is hardly easy viewing. The directness and emotional rawness of its content make it in some ways more painful, not only because there is no longer the arguable relief of hellish farce, but also because of the surprising calm and visual beauty that Oppenheimer supplies as a foil to the extremity of the content.

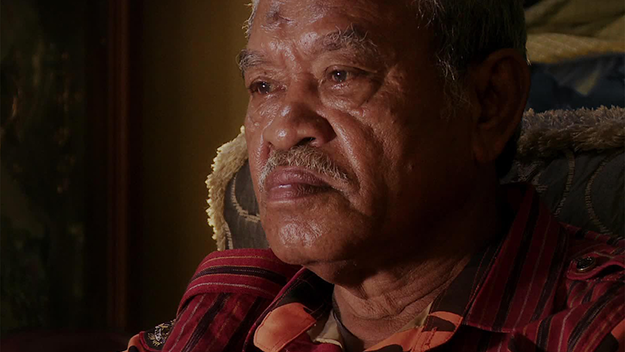

Shot in Medan in North Sumatra, the film focuses on Adi’s family. His two parents are now extremely old: his very ill, skeletal father is apparently over 100, but believes that he is only 17. Adi was born in 1968; three years before, his brother Ramli was murdered by local death squads. In the film, Adi sets out to confront Ramli’s murderers—prominent members of the community who openly pride themselves on their involvement in the slaughter of the Sixties. Throughout, we see Adi calmly and silently watching footage of the killers that Oppenheimer filmed in 2004. Then, in a series of visits, he confronts them himself, getting them to open up—not to a stranger who could be seen as a detached journalistic documenter, but to someone whose entire life has been lived under the shadow of their crimes.

What is remarkable is how little the killers attempt to downplay their actions or deflect responsibility: there is no recourse to the classic “only following orders” defense (barring one remarkable instance, which we’ll come to), and no one claims merely to have been an onlooker. One man even produces an illustrated book recording his exploits, with sketches “to bring the story to life.” The nearest we get to anyone playing down personal responsibility is the argument that it was all just politics. One man claims that the killings of the mid-Sixties were “the spontaneous actions of the people.” But a million people were killed, Adi objects. “That’s politics,” his interlocutor counters.

In fact, the killers are more willing to talk than others. Adi’s mother, Rohani, says that she would rather he didn’t uncover these truths, nor seek punishment for the culprits, local notables that she crosses paths with every day: “In the afterlife the victims will take their revenge. There’s no point raising it now.” Later, the son of one of Ramli’s killers says to Adi: “Let’s forget the past and get along like the military dictatorship taught us” (this line is so sublimely quotable that you can’t help wondering whether some poetic license has been taken in the subtitling).

But most of all, people are willing to talk—and not just to talk, but to re-enact, to show Oppenheimer and later to tell Adi how and where their deeds were done. Two elderly men demonstrate exactly how Ramli’s penis was cut off, one of the pair obligingly bending over for the purpose. Given the enthusiastic reconstructions in The Act of Killing, you wonder whether there is something specific to Indonesian culture that makes people not want merely to confess, but to re-enact, dramatize. One of the most revealing moments in The Look of Silence is dramatic in a different sense, as a killer adopts the first person to convey his victim’s ordeal: “After my head’s hacked off, I’m kicked into the river.” It’s a form of identification that is as close as any of these criminals comes to actual empathy.

The confessions are horrific—not least because of the mixture of pride, calm, nostalgia, and a kind of disbelief (as if to say: can you believe the crazy things I did when I was young?) on the perpetrators’ part. One of the most shocking revelations comes when death-squad leader Inong Sungai Ular says that some people went crazy from killing too many victims, but that there was a way to avoid going crazy: drink your victims’ blood. We tend to reassure ourselves with the thought that murderers are likely to be driven mad by their crimes, to forever endure the torments of the damned. Oppenheimer’s films suggest this isn’t the case: the killers he depicts seem to live with their crimes only too cheerfully, and it’s a moot point whether guilt is truly involved. If anything, they have not subsided into madness, but assumed a socially approved eccentricity, living out exaggerated stone-killer personas even into their dotage. But just like the retching Anwar Congo in The Act of Killing, Inong loses his cool here. He complains that Adi’s questions are “too deep,” but undeterred, Adi accuses Inong of lies and propaganda; the old man can only respond by gasping silently, mouth moving helplessly like a fish’s maw, his bravado at last turned to abjection by the kind of accusation he’s clearly not used to.

Even these grim moments of truth are nothing compared to the sequence involving Adi’s 82-year-old uncle, Rohani’s brother. It emerges that the old man was ordered in 1965 to guard prisoners, Ramli among them. The classic excuses begin: “I was ordered to guard the prison, so I did.” In that case, he was part of the killing, Adi says. The old man replies: “I was ordered to defend the state, so I didn’t feel that way”—and besides, he had to save his own skin. Then he comments about the victims: “I was told they were bad people. What’s more, they never pray.” The scene ends with the old man uttering an ineffectual “How dare you,” followed by a weak smile, a sort of gurgle, and a pained look. But any satisfying catharsis we might derive from this scene is undercut when Adi takes the news home with him: he tells his mother about her brother’s guilt. She seems to greet the news with her characteristic composure, but you can’t help wondering about the ethics of the drive to revelation at all costs, when it involves telling the truth to an elderly woman whose life has already been destroyed by criminals.

In contrast to the sometimes lurid tenor of The Act of Killing, and despite the extremity of its own content, Oppenheimer’s follow-up has a calm, contemplative tone. The silence of the title is echoed by moments in which he cuts out natural ambient sound and replaces it with the insistent hum of crickets and other insect noise, as in the eerie night shots that bookend the film; these rhyme with close-up shots of jumping beans, the insects they contain struggling to emerge into daylight, just like the facts revealed in the interviews. Oppenheimer opts for visual composure and beauty that offset the horror and convey a sense of life’s tenaciously continuing in the face of grief: notably, shots of Rohani sitting among trees or inside against bright purple curtains. These contemplative moments, Oppenheimer has said, were modeled on Ozu and Bresson, but Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s rural scenes also come to mind.

Oppenheimer could be accused of aestheticizing content that, some might argue, deserves to be delivered in the most unvarnished way possible; yet the film’s formal elegance emphasizes Adi’s calm and his role as a seemingly impassive listener, his silence having something of the function of a psychoanalyst’s, establishing a space in which repressed truth can emerge freely. And the film’s seeming gentleness is offered as a striking counterpoint to the urgency of its content and its very concrete import for Adi, whose manifest bravery is quite awe-inspiring. More than once, his interviewees tell him that killings could start again at any time, if challengers of the status quo step out of line; Rohani fears that Adi could be poisoned by one of his subjects; his worried wife asks him about the consequences of what he’s doing. Indeed, after the filming, Adi and his family had to move to another part of the country, where human-rights campaigners could help ensure their safety. As a reminder of how risky this undertaking was, for its Indonesian participants most of all, it’s worth nothing that the film is in fact co-directed by Oppenheimer and “Anonymous”; the word “Anonymous” occurs more times that I could count in the end credits, just as it did in The Act of Killing.