Atrocity Exhibitionism

A pallid man, his face inexpressive, makes his way through a death factory. He’s at work, a functionary; his job is to guide people calmly inside, make them undress, then enter a room, for purposes of hygiene, it would appear. He routinely fulfills his duties, quickly collecting the valuables of those you can hear screaming and banging on the doors of the gas chamber they are now locked within. Minutes later he will be dragging their naked corpses away and cleaning the area for the next round. This is the world Son of Saul inhabits: a film willing to grant an inside view of a Nazi extermination camp, aiming for a cool reenactment of the unspeakable incidents that have occurred there.

The first international reviews of Son of Saul, a Hungarian production, were glowing: critics found it “galvanizing,” regarded it as “cinema at its most powerful, artful and stimulating,” “both terrifying to watch and too gripping . . . to look away.” Almost none of those early takes on Son of Saul forget to mention its polarizing nature—but, as it turns out, nearly all online coverage so far only bears witness to the undivided fascination of rapturous pundits. What does this universal acclaim focus on? “Courage” seems to be the word most prominent in these reviews. True, one needs a certain amount of chutzpah to take on this subject—especially if you’re a first-time feature filmmaker. László Nemes, 38, born in Budapest, has lived in Paris and New York and worked a decade ago as an assistant to ultra-existentialist Béla Tarr. Admittedly he has managed to pull off his debut with a bang. For Nemes is not simply providing us with yet another Holocaust drama. He is trying to reinvent the history of Holocaust cinema, to use the memories of survivors as the basis for an innovative art-house thriller. Son of Saul is set in a carefully chosen time and a very concrete place: it is October 1944 in Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most infamous of Nazi death camps. Is that the place for a thriller? Was there suspense inside Auschwitz?

Most critics happily brushed aside spoilsport considerations of this sort, feeling relieved by the simple fact that The Holocaust Movie, that dreaded subgenre, suddenly looked so new, so exciting, so vital. The problem is: vitality is not what the Shoah was all about and excitement was not exactly its chief characteristic. In its pursuit of controversy, Son of Saul plumbs unforeseeably new depths of revulsion.

Son of Saul

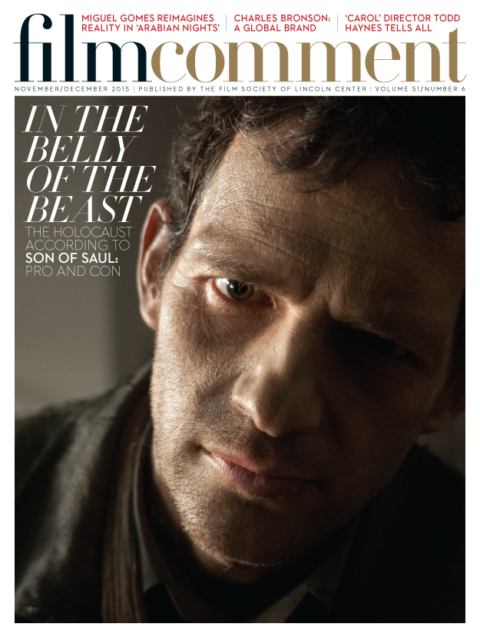

Winning one of the top trophies at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the Grand Prix, Son of Saul is indeed a provocative vision. The story revolves around an insane project, the mission of Saul Ausländer, a member of the Jewish Sonderkommando, played with great intensity by nonprofessional actor and poet Géza Röhrig, his mien fittingly numb and traumatized. While mechanically taking care of his tasks, Saul attempts to prevent the corpse of a boy (who he claims is his son) from being dissected and incinerated, hoping to find a rabbi among the prisoners to formally bury the child in the midst of all the slaughter. This somewhat absurd motive drives the minimalist plot: the search for redemption through sacrifice, an act of faith in a world beyond comprehension. Risking his own life, Saul sets himself a goal, kindling a spark of humanity in the face of the utmost barbarity.

Saul’s quite unrealistic freedom of movement within the camp is the dramaturgical prerequisite: it allows him (and us) to witness the power structure and manipulations within and around the Sonderkommando, all the bribery and theft, the mechanisms of industrial mass murder. As an art-house experiment that refuses sentimentality and character identification, it is the antithesis of Spielberg’s Holocaust—but like Schindler’s List, it remains at a distance from the reality it reaches for, no matter how hard Nemes tries. The camera, capably handled by Mátyás Erdély, follows hard on the protagonist’s heels, always alongside or behind him, creating the illusion of total immediacy, of complete immersion in this man-made inferno.

The atrocities remain largely off screen or out of focus, emphasizing the obscenity of the film’s sound, a collection of noises of doom, an atonal opera of bellowing, beating, and butchering. One shudders to think what it must have been like to shoot and record the sound for this film: what is it like to make extras simulate the sound of being gassed to death? How do you go about choreographing the Sonderkommando’s labors with a pile of naked female corpses? In the end, Son of Saul is an exploitation film not despite but because of its technical skill and resolute cunning. And it does not—unfortunately—require courage to experience.

Purchase the November/December issue to continue reading this feature.