It’s About Time

The title of Richard Linklater’s new film is misleading: Boyhood isn’t really about boyhood at all. True, it charts the nervous insecurities, roiling family dramas, and quotidian travails of a particular boy. And there are connections to be drawn between this film and the images of maturing young men crafted by other directors throughout the history of cinema: François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel, for example, offers a parallel, while Gus Van Sant’s gritty young hustlers in My Own Private Idaho and Larry Clark’s wiry boy bodies in films like Kids and Bully offer counterpoints. But at its core, Linklater’s attentive portrait of a Texan boy named Mason is less about what it means to be a young male than it is an evocation of another key theme in the filmmaker’s body of work, namely time. And not just time as a philosophical concept, but our time, the present moment, and what it means to be alive now. Right now.

The film focuses on Mason (Ellar Coltrane) as he and his sister Samantha (Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter), mother Olivia (Patricia Arquette), and father Mason Sr. (Ethan Hawke) learn, grow, and fight, ignore, and taunt one another, facing life’s myriad ups and downs over the course of a dozen years. What makes Boyhood so remarkable, though, is that Linklater actually shot the film in short annual increments across 12 years, so that we witness not just the arc of a story but the actual physical and emotional transformations of the characters—and the actors—as they grow and age. Accordion-like, the film collapses those 12 years into just under three hours. The effect is stunning.

Mason/Ellar slowly transforms from a boy in first grade to a young man who, at age 18, is ready for college. His sister also grows up before our eyes, from a bratty kid bent on harassing her younger brother to a pensive young woman pondering what’s next in life. Their mother endures a series of bad partners while trying to build a career and take care of her family. And their father drifts in and out of their lives, a goofy boy in a grown man’s body who refuses to acquiesce to adulthood and its responsibilities, until he capitulates two-thirds of the way through the story, trading in his prized GTO for a minivan to appease a new wife and baby.

Mason and Samantha are little kids, then tweens, and then teens, their soft and round young faces becoming more angular and specific, their bodies elongating—Mason develops a slow, lanky insouciance, while Samantha turns into a dark-eyed, petite twentysomething. For Olivia and Mason Sr., the transformation is more subtle, but no less striking as time marks its passage across their faces, creasing their eyes, while the weight of wisdom settles over their hunched shoulders.

Linklater’s latest temporal gambit shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. Anyone familiar with the director’s increasingly sophisticated body of work knows that time is a recurring theme. In films as radically diverse as Tape (01), which unfolds in real time, or Waking Life (01), in which the story’s dreamy meandering creates the sense of a continuously unfolding present, Linklater has repeatedly explored the vicissitudes of temporality, and line after line of dialogue in these movies reflects on the subjective experience of time, or questions its philosophical significance, or considers its sly complexity. “Time goes by, and people cry, and everything goes too fast,” sings Céline (Julie Delpy) at the start of Before Sunset (04), for example.

Indeed, Linklater comes closest to the feat of Boyhood and its temporal exploration with his Before Sunrise/Before Sunset/Before Midnight trilogy, a masterful chronicle of love and marriage similarly shot at intervals, in this case spanning 18 years. The story begins with Before Sunrise (95), when Céline and Jesse (Ethan Hawke) meet on a train. Jesse convinces Céline to join him in Vienna for the evening before he catches a plane home, and the two spend the next 12 hours together. The film continuously reminds us of time—we’re aware of the pair’s constraints, and the half-day shared between them feels very much like real time. And this sense of real time is enhanced by several particularly long takes, including a beautiful unbroken six-minute shot on a streetcar as the couple talks. We can feel the present moment unfolding before our eyes.

The story picks up nine years later with Before Sunset, a film that bumps the temporal experimentation up a notch by making the two-hour movie cover a two-hour span. Once again, we experience a sense of urgency due to Jesse’s impending departure and the literal reality of the minutes passing. Simultaneously, we also feel the pull of the past, the sense of longing and loss for a relationship that never had time to blossom. These two temporalities merge overtly in the opening shots, as Linklater introduces a series of flashbacks, intercutting imagery of the characters in 1995 and in the present; on a metaphorical level, the images from Before Sunrise imbue Before Sunset with an aura of memory—recollections of a woozy past rich with ardor underscore the urge to rekindle old yearnings.

With the newest film, we lurch forward another nine years, into a marriage and a sense of intimacy fraught with tension, bitterness, and the weight of time spent together. Before Midnight (13) is set in Greece as Jesse and Céline, along with their twin daughters, try in vain to enjoy a vacation together. If the previous two films delight in their ability to conjure the delicious pleasures of early romance and erotic possibility, Before Midnight burns with its unerring portrait of lovers who feel like they have exhausted all the possibilities and are thus stuck not with the unknown but the known. They comprehend all too well each other’s irritating foibles, disappointing flaws, and pettiness. Céline’s self-righteousness is grating, and Jesse’s immaturity—after all these years—is infuriating. Bickering has replaced flirtation; disdain has replaced desire; and the way forward requires a new reckoning with intimacy. The temporal experimentation in this film is less overt than in the previous two films in the trilogy—the film is structured as a series of vignettes. Each segment, however, boasts a vivid sense of the present tense thanks in part to the use of long takes once again.

Overall, the brilliance of the trilogy lies in its beautiful demonstration of how time unfurls, not necessarily forward in an easy and smooth progression, but in fits and starts, in moments of searing intensity surrounded by years of relentless longing and frustration. Time opens up into a languorous sprawl, which might concentrate in one moment, then clip along in a blur of months and even years.

The trilogy achieves something else quite remarkable: it charts Linklater’s two-decade maturation, and that of a generation that grew up alongside him. And it’s this sense of maturation that infuses Boyhood, catapulting it beyond a typical indie-film narrative to something far more ambitious in scope.

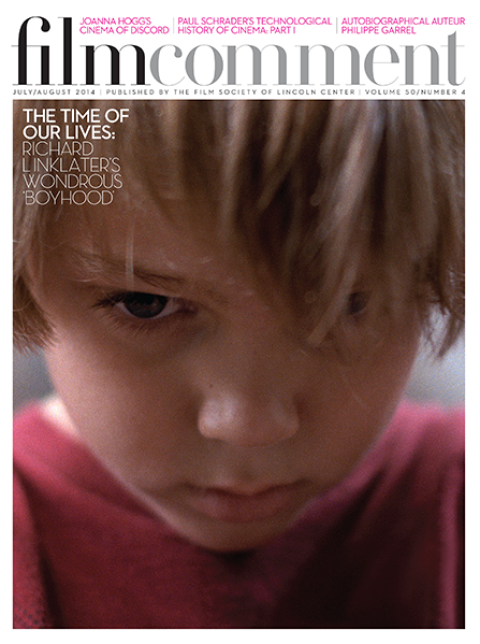

Boyhood begins in black with just the sound of a guitar strumming. It’s the opening riff of Coldplay’s “Yellow.” Then we see a blue sky dotted with puffy clouds, and as the lyrics begin—“Look at the stars, see how they shine for you”—the film reveals a close-up of a boy’s face (one that recalls Linklater’s own boyish looks). It’s Mason, and he’s lying on the grass, his pensive eyes gazing upward, and in both his dreamy countenance and his sense of wonder, we’re invited to consider the passage of time through his perspective, and therefore with interest, curiosity, even serenity. The film’s point of view will embody these qualities throughout. A minute later we meet Mason’s mother, Olivia, and a few minutes after that, the boy is riding a bike, then spray-painting graffiti, watching TV, bowling with his dad. There’s a violent stepdad, baseball games, camping trips, visits with grandparents, the prom, and high-school graduation. There are quiet conversations, brooding accusations, and surprising revelations. We move from age 7 to 8 to 9, and then suddenly at some point—oh my God!—Mason is a sulky teenager with long stringy hair and pouty lips. One event rolls into another, time unfolds, and, as in so many of Linklater’s films, there’s no traditional narrative structure to force conflict, no three acts to dictate development. Instead, a series of non-hierarchical situations take place, or perhaps more accurately in this case, they take time.

Hawke has described Boyhood as an example of “human time-lapse photography,” and in so doing, he identifies the film’s essential feat: it returns cinema to its original mandate, to reflect reality as it occurs in time in a sequence of images. This is an important point. The displacement of celluloid images by digital images has been a consistent source of cultural anxiety for more than a decade now, as has the concomitant loss of trust in the veracity of images. Distrust of the digital is wrapped up in our larger ambivalence about technological progress, and our conviction that the modern condition of living in a state of distraction is directly tied to the dizzying array of new devices.

Linklater, however, renews our expectation of cinema as a realm of wonder—but not by advancing its techniques or reveling in its increasing capacity to reshape reality in its portrayals. Just as the goal of time-lapse photography is to present normally imperceptible phenomena for scrutiny—flowers blossoming, clouds tumbling across the sky, and so on—he finds a way to give us the lives and bodies of his characters, who grow and change against the backdrop of the world and its events.

Boyhood allows us to move back and forth between the figure and ground of story and history, between fictional characters and our own world, and in the process we witness the passage of time for a sustained and unparalleled duration.

We live in an era that celebrates the self-regarding glimpse (selfies), that has found some strange pleasure in the repetition of seven-second video loops (Vines), and that has even engineered something as ineffably ephemeral as the Snapchat image that vanishes after 10 seconds. Time as it’s represented in contemporary image culture is instantaneous, fleeting, and quickly forgotten. Looking at our culture more broadly, we constantly fret about the accelerating pace of contemporary life and about the future, which used to sprawl in front of us across a vast horizon and now looms all too close. Even glaciers are moving faster, and events that were previously calculated to take place in 500 years are now supposed to happen in 50. Time is no longer thought of in terms of progress or a contemplative unfurling of placid duration. Against this backdrop, Linklater proposes a different vector: he invites us to be present—to look at the stars and see how they shine for us.

A year or two before Linklater began shooting Boyhood, author, economist, and “technology thinker” W. Brian Arthur argued that we need to adopt a new kind of knowing to align with a technology-based economy. In a world characterized by rapid change and technological development, it is no longer enough to rely on previous experience or old frameworks for understanding and knowledge. While previous eras emphasized order, determinacy, and stasis, our current era emphasizes, in Arthur’s words, contingency, indeterminacy, sense-making, and openness to change. In the 2005 book Presence: An Exploration of Profound Change in People, Organizations, and Society, Arthur described a new way of knowing in this context, explaining: “You need to ‘feel out’ what to do. You hang back, you observe. You’re more like a surfer or a really good race-car driver. You don’t act out of deduction, you act out of an inner feel, making sense as you go. You’re not even thinking. You’re at one with the situation.”

In a sense, this way of knowing is what Linklater represents in Boyhood. We’re invited to hang back and observe rather than rely on conventional story frameworks. We’re asked to feel and empathize with Mason and the other characters rather than enjoy the usual roller-coaster ride of dramatic conflict. We’re asked to be open to indeterminacy and change. Can we accept the film’s invitation to be at one with the events on screen?

A new era requires a new sense of time, and dozens of artists, especially media artists, have been engaging with time as a topic—from Douglas Gordon’s iconic 1993 video installation 24 Hour Psycho, which slows Alfred Hitchcock’s 104-minute film down to last 1,440 minutes, to Christian Marclay’s 2010 The Clock, which excerpts and arranges snippets pegged to certain times culled from the history of cinema to create a 24-hour chronicle. An army of media artists, including Sharon Lockhart, Tacita Dean, Bill Viola, Mark Lewis, and Candice Breitz, to name just a few, participate in similar temporal investigations with films, videos, and installations. Taken together, this work disrupts the easy forward flow of the past rolling into the present toward an oncoming future, in order to explore new configurations. Time is suspended and questioned; it is reconfigured, recombined, reoriented.

Linklater bridges the gap between these more art-oriented projects and contemporary narrative cinema. He offers us a new sense of knowing time by inviting us to be present as it unfurls. His perspective is deftly formulated by Mason, who says with wonder toward the end of Boyhood: “It’s as if all of time unfolded so that we could be here.” It has, asserts Linklater. It has.