Over the course of the seventies more than 40 Chilean filmmakers went into exile in France. One of them was Raúl Ruiz. He left Chile for Europe a month after the military coup that replaced Salvador Allende’s Socialist government with Pinochet’s hard-line regime. The majority of Ruiz’s over 100 subsequent films—many of them edited by his wife and fellow expat Valeria Sarmiento—were made in his new home country, of which he became a citizen. Towards the end of his life, though, he returned to Santiago to shoot what became his final work. Aware that he was dying, Ruiz intended the film to be shown posthumously. He passed away in Paris in August 2011, but he was buried in the country of his birth. Night Across the Street, his final testament, premiered at Cannes last year.

The film is based on two stories by the Chilean writer Hernán del Solar, but typically, it’s not so much an adaptation as what Ruiz called an “adoption,” incorporating references to certain of his own films, his cinematic influences, and personal history, and imaginative twists and turns of his devising. The nominal story centers on Don Celso (Sergio Hernandez), an elderly clerk nearing forced retirement whose wind-up alarm clock dances noisily when it’s time to take his pills. Don Celso is keenly aware of and even obsessed with the passage of time. As he discusses his life with exiled French writer Jean Giono (Christian Vadim), he also knows that he will soon die.

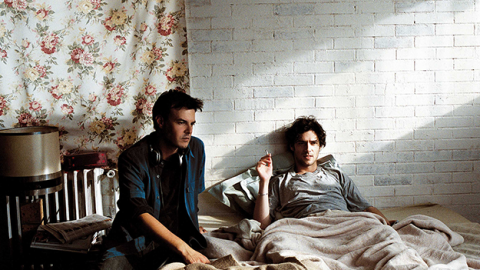

While he anticipates his imminent murder by a mysterious assassin, images from his youth appear. He sees an adolescent self (Santiago Figueroa), nicknamed “Rhododendron,” in deepening friendship with the aging Long John Silver (Pedro Villagra), and explaining the modern world to Beethoven (Sergio Schmied), his favorite historical figure, whose need for recognition as a great artist gives his own life purpose. As the composer examines a battery he’s picked up from the ground during a funeral procession, little Rodo tells him that machines are going to do everything for men. Beethoven walks away muttering, “How sad.”

A viewer might find this moment irrelevant, but then again why not include it? Indeed, after Don Celso’s boss tells him that he’s lately become incoherent, the film itself seems to come to the defense of incoherence. The port city of Antofagasta, rendered flagrantly artificial in Night and filled with old-fashioned, oddly gleaming buildings, exists outside of time. Past, present, and future, and illusion and reality, dissolve as the film’s scenes line up like marbles, all of equal weight and value. This approach to storytelling is present throughout Ruiz’s body of work, whether lovingly star-studded or blithely obscure. In his 1995 book Poetics of Cinema 1: Miscellanies, Ruiz rejects what he calls “central conflict theory”—the Hollywood- inherited notion that a story must work towards resolving a single driving conflict—in favor of a “shamanic cinema” which can summon real and imagined memories in intuitive sequence.

Don Celso lives in a world in which anything seems possible at any moment. Yet the free-associative mind dictating Night Across the Street’s action belongs neither to him, nor to any other character’s, but rather to the film itself. Ruiz aimed to create entire films with which viewers could identify. Night, which liberates its lowly clerk from the dread of a humdrum life, looks with eyes liberated from many kinds of dictatorships—the dictatorship of narrative, as well as those of bureaucracy, patriotism, power worship, and official histories.

Throughout his life, Ruiz sought to respond to the world’s finite number of official histories with an infinite number of imagined stories, free of all constraints, including mortality. “You can’t kill yourself. You lend yourself to death,” Don Celso tells Jean Giono, echoing one of Ruiz’s favorite maxims: “Dying is no big thing.” In time, the film shows death to be just a place across the street, and when people go there, friends await them.