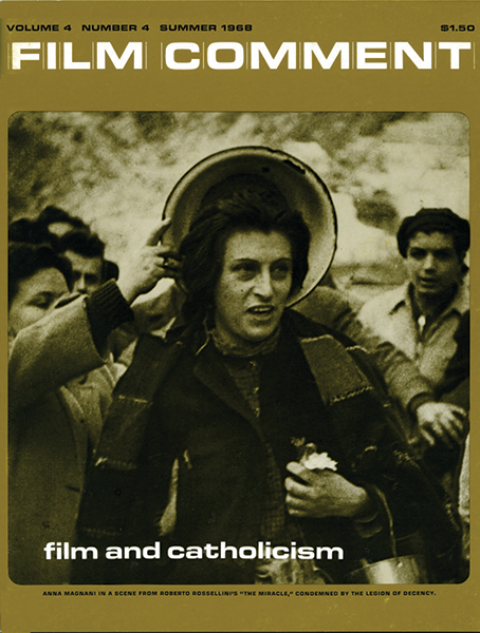

Interview: Satyajit Ray

This interview with Satyajit Ray was tape-recorded by Blue as preparation for his book on the directing of the non-actor in film. This special research has been sponsored by the Ford Foundation. Blue, at the time of the interview, was visiting India while directing A Few Notes on Our Food Problem, a color, 35mm, 40-minute U.S. Information Agency film on the world food and population problem, shot by Stevan Larner. Sailen Dutt, assistant to Ray on most of his films, assisted with the recording. Ray was at work then on a film that he described as a commercial “adventure story with big name stars.” Blue describes Ray as “a tall man, over six-feet-one, enormous for an Indian, whose deep and resonant voice surprises more than his height, because of his ability to manage—as a patrician might—the niceties of English speech.”

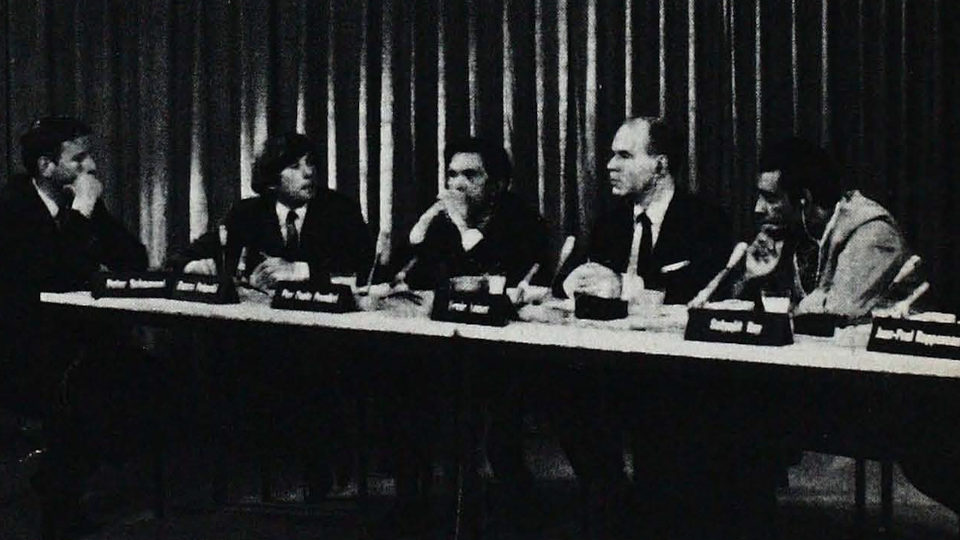

Ray, far right, at panel discussion in Berlin, 1963. With him, from left are Peter Schamoni (a German director), Roman Polanski, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Erwin Leiser.

SATYAJIT RAY: I have the whole thing in my head at all times. The whole sweep of the film. I know what it’s going to look like when cut. I’m absolutely sure of that, and so I don’t cover the scene from every possible angle—close, medium, long. There’s hardly anything left on the cutting-room floor after the cutting. It’s all cut in the camera.

For example, the mother-daughter fight scene in Pather Panchali—that was all in my head and I merely told my editor to join this strip, now that, now this…. And the strong scene where Durga dies—lots of shots there and the editor just didn’t know what he was doing. I had all the strips in my hand and then I popped them one after the other, now a bit of this, a bit of that. The editor just came in to help, you see, because we had to catch a deadline.

But I have an editor who’s very good indeed; he has often very creative suggestions. In small things, you see—particularly in long dialogue scenes involving three or four characters, where you can make small changes all the time, make improvements, he has very good suggestions.

I understand that in many of your films you have been at the camera yourself.

Ever since The Big City, which I shot in 1962, 1963, I have been operating the camera. All the shots, everything. It’s wonderful to direct through the Arriflex because that’s the only position to tell you where the actors are, in exact relations to each other. Sitting by or standing by is no good for a director.

I find that I am not able to both direct and shoot.

I find it easier, because the actors are not conscious of me watching, because I’m behind the lens. I’m behind the viewer and with a black cloth over my head, so I’m almost not there, you see. I find it easier because they’re freer, and particularly if you’re using a zoom. I am doing things with the zoom constantly, improvising constantly.

When you work with a cameraman, however, he is always saying—“Let’s have one more take.” I generally say—“Why? Tell me why?” He’s never able to specify exactly “why”—he is not sure, you see. Whereas, I am sure. Only the director can know when the technical operation needs to be all-important, you see. Whereas in certain shots maybe it’s not the operation that is all-important but it is something else that is really vital. So even if the panning is a little this way [making a jerky movement], it doesn’t matter. And the question of re-takes comes up also when you are working with very limited raw stock, you see. It’s mainly because of that that I have started operating the camera myself.

Then you operate the camera during the rehearsals also?

Yes, otherwise it’s pointless. Except there is a first rehearsal where I’m not behind the camera, where I’m just watching the whole thing for all the details of acting, you see. And just before the take, if it’s complicated, I have at least two rehearsals when I’m on the camera, to see whether I can actually do it, whether my limbs will permit it, you see. Because sometimes you’re in the most terrible position, lying down or half-reclining, and I take off the panning handle, I grab hold of the other sort of thing that sticks out and I grab hold of the whole camera and turn it like that, on its pivot.

Personally, I think that Subrata Mitra’s camera work is better than Raoul Coutard’s, but Gianni Di Venanzo I admire tremendously. 8½ is something extraordinary, I mean the daring things that Di Venanzo does there and pulls off. Largely, of course, it’s the director, too; it can’t be just the cameraman who is devising all that, all those over-exposed shots and everything that comes off.

Sometimes cameramen do this kind of thing for no reason at all, and that I don’t like. I mean, just tricks for tricks sake, which quite a number of these New Wave directors do. I mean Godard does it all the time, hand-held for no reason and you can see it going all the time. A long scene with Belmondo in Une Femme Est Une Femme, sitting in a bar or somewhere, talking, talking, and you have the camera hand-held, and you watch the edge of the screen and can see it wobbling all the time [Laughs]. And you tend to watch that not the action within the frame. You become interested in how well the chap was able to steady his camera.

Well, Godard’s is another style altogether, you see, where you use all kinds of things completely amateurish, completely improvised, and it all sort of hangs together as a kind of collage. Good, bad, indifferent. But that’s another category of films, I think.

I haven’t seen any cinéma vérité except for Jean Rouch’s Les Maîtres Fous, which he shot in Africa, a rather horrifying film but very impressive, very strong, I must say. And all a single man’s effort. It’s just one man, Rouch, doing everything. I met Richard Leacock at the Flaherty Seminar in 1958, but I don’t know his cinéma vérité work, nor do I know Chris Marker in France.

Although I don’t know cinéma vérité, I can see that it can be very interesting, and valid, in a way. But again, a different category, you see. I think that Frances Flaherty was slightly disappointed in my method of work, because she had thought that in Pather Panchali they were all actual villagers. But it doesn’t really matter whom you use, because it’s the ultimate effect that counts, you see. In all art it is like that.

I use the Arriflex. Because you can do very small zooms that are not noticeable, you can get your emphasis all the time with a zoom, and it’s lovely with that. And sometimes you don’t even notice that. You are not supposed to, most of the time. It’s not zoom-zoom, like that, it’s just a little bit. Sometimes combining with a tracking shot you can zoom in. I love the zoom. I think it’s wonderful, particularly now. For example, for a certain insert . . . what you can do is a little zoom.

How do you direct dialogue?

All actors are afraid of pauses because they can’t judge their weight. So with Sharmila Tagore in The World of Apu, I would say—“Well, you stop at this point and then resume when I tell you to resume.” So she would just stop and look at a certain point that had been previously indicated, and then I’d say—“Yes, now go on,” and she would resume. So the pauses would be there as I would need them. Otherwise, actors are terribly afraid of pauses, and it’s only the greatest professionals who know the real strength, the power, of pauses. For all non-actors and for inferior professionals, they just can’t judge pauses at all. For me, pauses are very important: something happening, waiting for the words, and when the words come you have that weight. So the pauses have to be worked out constantly.

Once he has memorized the line, it’s the hardest thing for an actor to make it sound as if he is thinking and talking rather than just mouthing lines. Sometimes there are certain words that don’t come easily. You must have the pause before a certain word. Not everybody is a linguist with a great command of vocabulary, so you have to vary it with actors, and those pauses are very significant. Sometimes you just can’t think of a word so you just hesitate, you see, and somebody else supplies it for you. So my dialogue is written like that, with a very plastic quality, which has its own filmic character, which is not stage dialogue, not literary dialogue. But it’s as lifelike as possible, with all the hems and haws and stuttering and stammering.

But you would not call it natural speech?

No, it’s not naturalistic but let’s call it “realistic.” It’s not as if it’s off a tape recorder, because then you would be wasting precious footage. You have to strike a mean between naturalism and a certain thing which is artistic, which is selective, you see. If you get the right balance, then you have this strange feeling of being lifelike, everything looking very lifelike and natural. But if you were to photograph candidly a domestic scene it wouldn’t be art at all. I mean, it could be interesting for certain revelations, but it wouldn’t itself be a work of art—a scene, whatever scene, unless you cut it. That’s being creative, you see. By being selective in your framing, in your cutting, in your choice of words, you are creating something artistic.

I think the cinema is the only medium that challenges you to be naturalistic, be realistic and yet be artistic at the same time. Because in the cutting is the creation, you see.

You shot Pather Panchali in sync sound?

Yes, absolutely, because it would be impossible to dub with a non-actor. Absolute disaster. I’ve tried it and it doesn’t work.

How do you dub? Do you use the French system?

No system. We devise our own system. I don’t even know what the French system is. Look, I don’t like dubbing because it’s too mechanical. I have devised a system of notation—I mean, you have to have a kind of guide-track . . . Sailen Dutt, my assistant, and several others, take notes or a code on the exact scanning of each word. Even if we do have a tape recorder, even if there is a guide-track, you need to do that. I play back and then make my own special notations for it, and then I work it from my notes, you see. Because you have got to have control yourself of how the lines are spoken. So that it sounds right, it conforms to the original speech. You have got to memorize it; you must know your lines.

When you go into the sound studio to dub the final cut, do you try to reproduce exactly what the actor has said in the picture?

Absolutely. But sometimes I try to improve. Most of my dubbing so far has involved, fortunately, professionals who have been able to do it with me. But somehow with Pather Panchali we had usable sound all the way through, more or less. Not much dialogue, and no crowds watching, because even whispering would create an enormous noise that ruins your track.

Yesterday we shot a scene in the village where you made Pather Panchali.

Did you? It’s unrecognizable now. It’s no longer pure. It’s spoiled. It was once very nice, indeed, with long areas of no huts, no refugee huts . . . [Note: the Pather Panchali village, like many others in Bengal, now contains refugees from East Pakistan as a result of Partition.]

Were people of that village cooperative when you began that first film of the Apu Trilogy?

Not in the early stage. No, they were fairly hostile people there. But we got to be friendly, and finally—because we were there for two years off and on—we got to be very friendly with them. They really missed us when we left. You can manage only by being polite with them, you see, sitting down and talking. They’re essentially nice people, but suspicious. To them all business has certain rather unpleasant associations. We were completely newcomers, nobody knew us, and today we wouldn’t have any trouble, except from people coming to watch.

For example, we have begun shooting our new film in Baraset, and the crowd has been increasing, and for the last two or three days we have had something like two thousand women and children watching. A wall was constructed around the compound, and outside the wall they would stand, looking over. And all the trees were full of people. And some of the branches gave way and a dozen people fell and collapsed, and one was seriously injured. Fortunately, we had a doctor in the cast, among the actors, and he gave first aid and sent them all to the hospital.

We found yesterday on location in your Pather Panchali village that we had almost 150 people around us—everybody excited and . . .

Yes, but at the time we made Pather Panchali, there was almost nobody watching. There were some during the first few days, of course, but then they lost interest in the actual work, so we could continue uninterrupted, absolutely. And nobody knew us, everyone was new, we had no stars. But this new film we are making has a big star, and he is the main draw of crowds, I think. But apart from that, nowadays shooting in a city street is almost impossible unless you do it with concealed cameras or dummy cameras or things like that. If you don’t use these means, then the shooting becomes too expensive. I shoot on a four-to-one ratio, you see.

Did you make Pather Panchali on a four-to-one ratio?

No, that’s the only film where I had scenes that eventually didn’t go into the film. Some scenes were not finished. And then I wasn’t sure of my cutting, so some of the stuff had just to be thrown away. The first two or three days work wouldn’t cut at all. Then later I sort of disciplined myself. You learn while you work. You learn quite quickly, in fact. We were forced to be economical, as you must when you have a ceiling to everything.

Of course, you have said that during Pather Panchali you did not have crowds disturbing the shooting and causing your actors to freeze up—but still, with so few takes, how did you manage to get relaxed behavior from non-professionals?

Sometimes it’s easier with non-professionals. I have no definite system. I use different methods with different actors. You have to modify your technique all the time. But you have to get to know the person you are working with, know his moods and his abilities and his intelligence. Sometimes I use them as puppets complete, and I do not tell them anything about motivation at all. I just try to get particular effects.

For example, the boy who played Apu in Pather Panchali—he was treated all along as a puppet. Completely. He didn’t know the story, only the vaguest outline. And it is really not a children’s story. It’s an adult thing with all the subtleties, really emotional.

Does this mean that you dictated his gestures?

Absolutely, down to the head movement—“Do this and that.” The first day I had some trouble.

It was a very simple shot of him walking, looking for Durga, his sister, in that field of flowers. Remember that? And that walk was so difficult to get right. So I put little obstacles in his way, which he had to cross, and it became natural immediately. Otherwise, he just walks like that [stiffening his body]. I had to put objects in his path and say—“you cross this piece of straw and then the next one”—not really large obstacles but things he had to be conscious of, to give him a purpose. That’s the most difficult thing to do—just walking, looking for somebody. Every turn of his head was dictated—“Now look this way!” I put three assistants at certain points, and A would call the boy and then B would call and then C. So the boy would walk, look, then hear a call, then walk again. It was like that. It’s the only thing to do. At first I didn’t work this way, but I immediately felt that something was wrong. So I sat down and thought it out and did it.

I hardly ever do more than three takes. It’s generally two. If the second one is not better than the first, then there’s a third take. I’ve never taken more than five or six, except for one shot in Pather Panchali involving synchronization with a dog. You see, when the confectioner comes the children run and follow him, and in the same shot you have a dog who is also supposed to run at a certain point. But this is not a trained dog, you see! The dog would be called, but it would just sit there and look up and not do anything. So that took eleven takes. I remember that very well because I had never had eleven takes to a shot.

One professional actor who let us down several times was the man who played the father in Pather Panchali. He was a professional of long standing, and he was muffing lines constantly because he was asked to do certain things along with speaking—combining action with speech—which I use very frequently, which I think is very important, which gives it that relaxed thing, you see. It’s both in work and talking.

You find actions to accompany speech constantly?

Yes, unless it is a scene that demands absolutely no action at all. In the second film of the Apu Trilogy, Aparajito, there is a scene towards the end where the mother is dead and the boy sits and cries on the little verandah, and there’s the old uncle smoking the hookah, and he sort of consoles Apu by saying—“You know, man is not immortal. Everybody has to die sooner or later, so don’t cry.” Now, that old man was a complete amateur. (He died the other day.) We found him in Benares on the grass. He had never seen a film, because he was living a retired life in Benares for thirty years with his wife, you know. I mean you find people like that. He seemed to be the right type, so we went up to him—we hadn’t cast that particular part yet—and I asked him whether he would be willing to act in the film. Immediately he said yes, why not? And then in this scene, the only scene where he needed to speak for a certain length of time, I couldn’t possibly cut because it needed to be a single set-up all the way through, to suggest that kind of gloom and, you know, hopelessness. I split up the dialogue into parts; between sentences he was asked to smoke, just take a pull at the hookah. Then stop for a certain length of time, then I would say go on. Well, he knew where to smoke, where to take a pull at the hookah, but he didn’t know where to resume speaking, and that I would dictate.

I understand De Sica uses quite a bit this method of handling actors as puppets, you see, telling them exactly what to do at every point. I felt that in Bicycle Thief; not with the boy so much as with the father. The boy was amazing, absolutely incredibly good. Particularly the last scene where he walks down and holds the father’s hand, where he’s crying.

I asked De Sica how he got that scene. He replied that he poked fun at the poverty of the boy’s family and made him cry. De Sica said—“I was so ashamed of myself when I got that scene . . . it was so shameful of me.” He said—“My little boy was so very proud and he lived in such poor conditions in the same room with his mother and father and his other brothers and sisters, and they all slept in the same bed, and yet he was terribly proud. And he didn’t want anyone to make fun of that, and so I made fun of it. And it made him mad and he cried and he cried and he cried,” said De Sica, “and then I got my picture.” And De Sica ended by saying—“Afterward I grabbed him and kissed him.”

It’s typical, yes. You use such methods, you always have to. Otherwise you can’t expect a child of five or six to be so brilliant in faking emotions, you see.

De Sica and his writer, Zavattini, both told me that their problems were to develop concrete actions within a scene so that, in the final analysis, the people were doing relatively simple things—picking up a coffee pot, closing a door, and so forth. The attempt to juxtapose all of these elements in the film made the person seem to be performing. Is there something of this approach in the way you construct scenes?

Very similar, yes indeed. In the domestic scenes of The Big City it’s all like that. Everyone is doing something and speaking at the same time, and the story is advancing and the drama developing and the relationships. It’s like that all the way through. Every scene has some sort of domestic action being performed all the time, and the time of day is being very strongly established in the lighting.

How did you handle the gradual changes of daylight in that film?

With Subrata Mitra and his assistant—who is now doing my camera work—we have devised a system of lighting whereby in a studio we can simulate daylight to a fantastic degree. It fools everybody, the best professionals. It’s a boost sort of light we use. If it’s a day-scene, we try to imitate available light by not using any direct lights; instead, we use bounce lights all the way through. Particularly if you saw Charulata—it’s my best film from many points of view. And in The World of Apu, his little room, that had a very convincing actual location atmosphere due to our lighting. Yet it’s a studio set. The lighting we use through the windows and also from the side of the camera is all bounce light, you see, and it’s very carefully graded for various times of the days. We may use a white card at various positions—here, there, like blackboards. Different greys, so that it’s one kind of lighting for a cloudy day, one for sun, one for mid-day, one for early morning—it’s all varied. In The World of Apu the matching of light is exceptional, and of course matching is not just a matter of lighting but it’s also the soundtrack, which is being matched all the time, because you’re carrying over sound from shot to shot, you see.

I read in American Cinematographer an article by Sven Nykvist, Bergman’s cameraman—they had just finished shooting Through a Glass Darkly—and Nykvist goes to great lengths describing the wonderful system that they have devised with bounce lights. Which we had been using for the last twelve years.

As I said, the Benares house where Apu lives is a studio set. We had a cloth stretched overhead, you see, for the light from above. Our lighting gives you a kind of dark eye-socket effect, but it doesn’t matter really, because it’s not a question of beautifying everybody. Ultimately it pays off, because you are sticking to a realistic mood.

But even on location, what we’ve been doing, instead of using those tinfoils and silver-paper reflectors—of course, you have to use those—but for all our close shots we have this enormous white cloth stretched so that you get that soft bounce. In Kanchenjungha, a color film, we had interior shots in the hotel, but we had no lights for color, so what we did was to use two or three large mirrors, about four feet square. We reflected the sunlight into the room onto stretched cloth, and that was just wonderful. You have to have sunlight, of course, to be able to do that; if it’s a cloudy day you’re finished. But if you have sun and you have mirrors, you reflect the sunlight into the room through the window. It’s worth it for the quality you get. You don’t feel the presence of lights around at all. They are not reflected in all sorts of little glistening props and things.

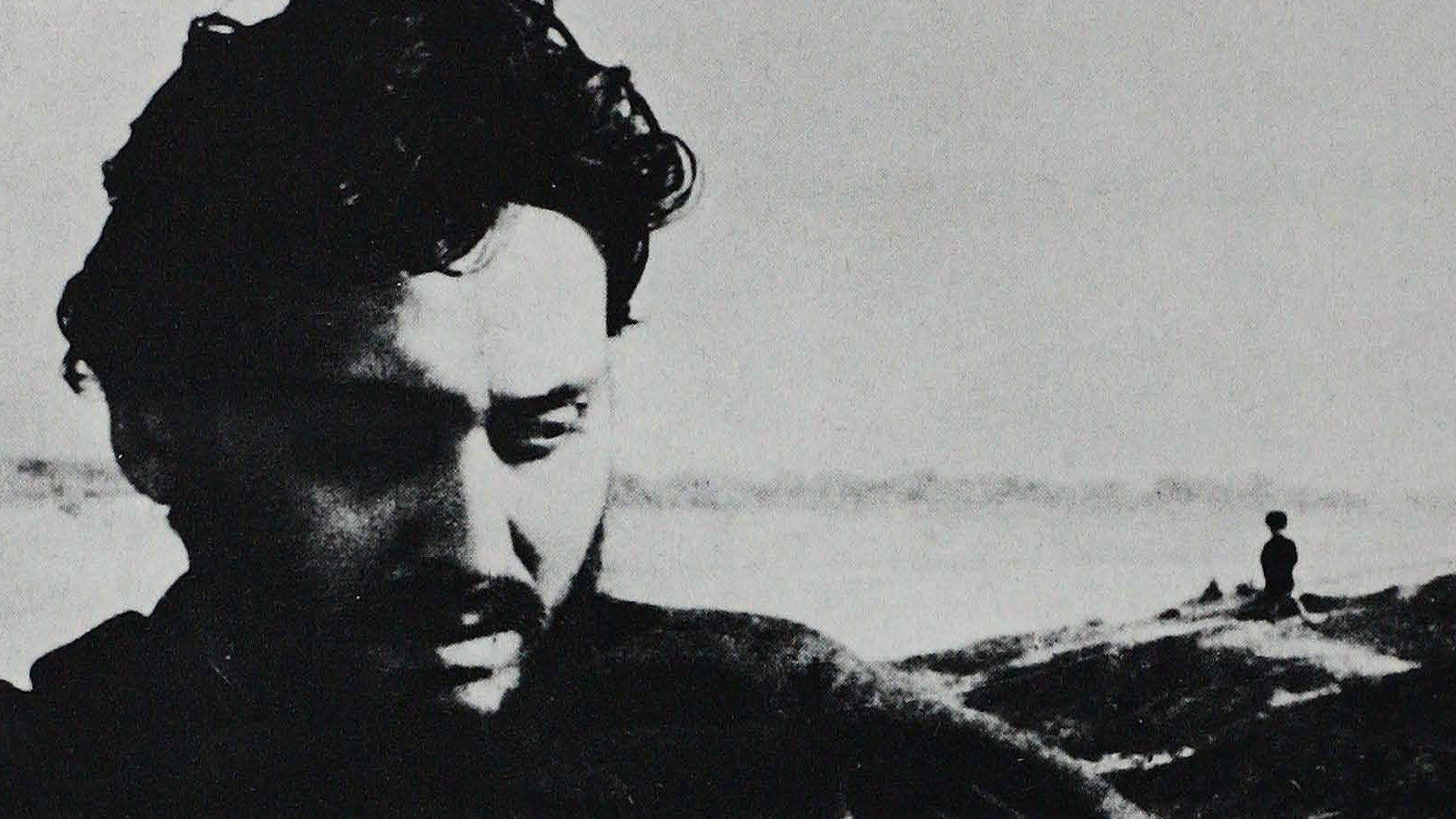

Pather Panchali

Why did you desire to work with non-actors?

I felt safer with non-actors. But there are certain types of stories and films that you can’t think of in terms of non-actors at all. I made quite a few like that—Devi or even The Music Room or Kanchenjungha. The last is a wordy sort of film involving a wealthy family.

So when you deal with a great amount of dialogue, you tend to prefer to use professionals?

I do, yes I do. Unless . . . you see, “non-actor” doesn’t necessarily mean a person without acting ability. I mean there are non-pros and non-pros; there are different kinds. The old lady in Pather Panchali I wouldn’t really call a non-actor because she had had some stage experience and she had the ability to memorize lines. That’s a great thing. Whereas, some non-actors just can’t remember their lines. This old man in Aparajito, for instance. He was a real, real amateur with no sense of acting at all. It’s only if you were able to convey to him a particular emotion, involvement or situation, if he was able to feel it, then he would be able to convey it, you see. But always relating it to some personal experience in his life.

I once asked De Sica about his handling of the old man in Umberto D…

Yes, but De Sica’s old man was the whole film there, you see, while my old man was there for only a week or something. That old man in Umberto D was a professor in an Italian university. He had very little to speak as far as I remember. He was alone most of the time. You have to direct an actor considerably if he hasn’t got the ability, because he doesn’t know the limits of his gestures and how far they are going to be exaggerated on the screen.

And so you must impose the gestures?

Oh certainly, all the time. That you have to do with professionals, too. I think most people in front of the camera have a tendency to over rather than under-act, even non-professionals.

Did you direct Duga, Apu’s sister in Pather Panchali, in this highly controlled, disciplined way?

Much less than the boy. Oh, she had great natural talent, the girl. I told her what I needed of course, because always you have to tell the actors what you need.

Sometimes I cheat—like suddenly you have a cracker going off right behind the boy Apu without his knowing it, and he does “this” and then you use it like that. We did that in Pather Panchali, particularly in the scene where Duga gets a thrashing from her mother after the necklace business, and the boy is standing and watching by the post, and all the expressions are sort of little tricks.

Did you use a firecracker at that point?

Not a firecracker exactly. He was made to stand up on a little wooden stool, and I had an assistant with a stick whack on the stool, you see, and suddenly the boy did this expression. Oh, that you do all the time, particularly with children. Because children are not always natural actors. Some of them are very hard to handle. You need all the patience in the world. And sometimes they’re just wonderful. The boy in The Great City, a very gifted boy, seven years old, had a wonderful memory for lines. I increased his dialogue, I added words as I went along, because I found that he was very good at speaking naturally, in front of the camera.

Generally, then, do you show your non-actors what gestures you want, or do you evoke them by saying do exactly as I say, or do you rely on such tricks as you’ve described to get reactions?

Such a trick would be only in special circumstances, for just a very brief insert sort of expression. But if it’s a sustained scene, then you can’t use such tricks, you see. You have to explain what you want. But even then, with small things like where to put the hand and which way to turn the head and where to take a little movement forward—all this has to be dictated pretty firmly.

Do you rehearse?

Not very much.

How can you get a four-to-one ratio without rehearsing?

Well, that has been the ratio so far. But there are lots of defects in all my films, with the one exception of Charulata, which I think is as near flawless as I could make it.

I rehearse at least once. Twice. Three times. Always, there is a little bit of rehearsal all the time. If it’s studio shooting, there is no rehearsing until the moment the set is completed, props and things, because I don’t rehearse as you rehearse a play in a drawing room. I can’t do that—read out the lines. Sometimes I read the lines out once, but don’t necessarily act it out. With a non-professional, I might act it out a little bit, but not too much. Not too much to completely dictate an acting manner to the person. I always like to find out what he or she has to give me in terms of acting, through her own ability, you see. I ask the person to act it out. First I read out the lines without movement, without anything, and then I dictate movement—“This is what you do, this is the way you pick up your little glass watch, or this is where you put water on the flower.” After the first rehearsal I use that as the raw material for little modifications, because then I know what they’re capable of. Sometimes they give me ideas, sometimes they do things that are even better than what I had conceived, you see, so I use that.

Do non-professionals lose their spontaneity?

In repeated rehearsal? Not necessarily. If you are having fifteen takes it gets the performance worse and worse—almost inevitably it gets worse. If the second take is not an improvement on the first there is bound to be a third take. But I never let the takes continue if I can help it.

What do you do if a non-professional child or adult freezes up? Has this happened?

With children, yes. One girl, one particular actress I couldn’t do anything with. So the entire part was completely omitted. Apu was to have had a girl friend in Calcutta. We had put ads in the papers; lots of replies, but nothing good. Then we found this girl who had the right looks. But in front of the camera she had mannerisms that just didn’t go with the part at all, and we couldn’t do anything with her. So I just dropped the part completely. She went out of the scenario. Her role, if we’d kept it, would have explained a little bit more Apu’s alienation from the mother. The girl was one of the elements in the city that drew him away from the village. But she is no longer in the film, and it looks a little mysterious, except that you explain it in terms of the inevitable adolescent sort of growing away from the mother, you see. It’s a convention, it’s something that happens, even without a girl friend being there. I suppose I’ve been lucky to a certain extent with my actors—because, for example, you can’t do anything about camera fright really. If they freeze up, there’s nothing very much you can do except give up for the day and try again the next day, or change the actor.

If I may be a little technical, I’m still amazed at this four-to-one ratio with non-professionals, and getting the results that you do. I suppose that this is partly due to the casting.

Yes, very much in the faces, in the voices, in the looks. Half the work is already done there, you see.

What kind of test do you make in casting?

I don’t make any. Generally screen tests are something that we don’t waste film on. Except in certain circumstances because a girl would look right but then something would be wrong with her speech or gait. Then I would want to see what she looked like in front of the camera, and so there would be screen tests. Normally if it’s a small part I don’t bother, but just the looks and then a couple of hours spent in this room, sitting and talking. That does it usually.

Do you do some things in order to adjust the person to this shock of being ill front of the camera? Do you build their confidence beforehand?

Well, I leave it to chance generally. Except that I get the crowd away sometimes, because I feel that if too many people are watching when a new person is facing the camera for the first time it may be difficult for him. But in any case the actor is surrounded by the crew, which is a small crew generally. It’s not a crowded place, the studio here, not as in Hollywood.

When you are shooting with non-actors, what procedures do you use in setting up the shot, in rehearsing it, and introducing the actors and technicians to the shot?

Well, I don’t generally make any distinction between a professional and a non-professional, you see. I don’t sort of make any special arrangements. “Look, this man is new so get away and let him be free.” Nothing of the sort. I just dump them in and see what happens.

Then what procedure do you follow in rehearsing the shot and setting it up for the camera?

I treat the children as adults, take them into my confidence. Except that I generally whisper my directions to the children. I never speak loudly to them. I sort of whisper into their ear, so that they think it something very confidential that’s being communicated, so they immediately sort of get interested. It’s all pre-planned. If it’s a location thing then I’m there several days beforehand. I make several trips and decide on the circumstances. Sometimes on location you have to make changes, improvise, because there’s a certain effect, the wind is blowing in a certain direction and you have the trees moving. You want to include that in the shot, so you change the set-up. But in the studio it’s all sketched out, you see, because I have my scenario in a graphic sort of form. It’s never sort of sheets of typewritten paper.

You have already spoken to the technicians, but have you always talked to the actors about the scene before you go out to do it?

Well, they know the scenario more or less, and they know which particular scene is being shot on a particular day, that they do know. Non-professionals also. I mean they all know the scenario. If it’s a big part, if it’s a considerable part, they know the whole story. Because again we have a reading session in which most of them are present, unless you have a very busy actor who can’t turn up on that particular day. Then I have another separate session for him, perhaps in my own home. So they know the story more or less.

And when you arrive on the set, on the location, your cameraman knows the angles already.

Yes, oh yes, unless I’ve made some changes in the previous evening, thought up something new, which r communicate to him immediately. The first thing I do the next morning when I’m on the location is tell him—“Look, I have this new angle.” For example, with this new picture we constantly have to make small changes in order to avoid the crowds.

Then immediately when you go on the set, and while the technicians are setting up, you are rehearsing, or do you wait?

I wait for everything to be ready. I rehearse after the lighting is finished.

Do you show your technicians any kind of run-through at all?

Just a bit of the movements. The movements here to here. If it’s a complicated scene involving something like fifteen people on the move all the time then you have to rehearse it with the actors, do it fairly carefully.

Except for large scenes with a lot of people you do no rehearsal until everything is set up?

Correct. Otherwise there is constant interruption. I don’t like interruptions when I’m rehearsing. But for movement, for lighting, naturally the cameraman has to know where the actors will go, what positions they’re going to take. So that is done, but the proper rehearsal begins after everything is finished. And immediately after the rehearsal I have the take. Immediately. While it’s fresh in their hearts, you see.

And there are no further interruptions from the technical crew after that point?

Small ones. Every cameraman will interrupt at least once during the final rehearsal. That is bound to occur but it’s nothing major.

In shooting Pather Panchali over a period of two years, did your actors start “acting”—rather than being pure non-actors?

They weren’t all amateurs—there were a few professionals in the cast. But we had great worries about the old woman, because it took so long to make the film and you don’t know what may happen in the meantime. During long periods when there was no shooting, we would make discreet inquiries as to her health, how she was feeling. Because we lost one actor half-way through—the confectioner, the man who sells the candies. As a result, there were two fat men in the film, two different ones, one standing in for the other. The old woman died two months after the film was completed, but she couldn’t see the completed film.

You got such a performance from her—for example, at the great moment when she comes back sick, after she has been ostracized by the family because she has accepted a shawl from a neighbor.

Oh, when she asks for a drink of water, yes. Those situations are so familiar. The actors can feel that what they’re being asked to perform is believable. The lines that they’re given, if they sound right and convincing and natural to them, you can get it. And certain things happen on location that don’t happen in a studio set, you see. They’re more relaxed somehow, surrounded by actual, natural things, trees and so on.

A new experience for me was a short-story film that I made as part of a television thing sponsored by Esso, part of a series called World Theater. They had something from Greece, something from Sweden, something from England, and they had three short films called the Indian section. One is the little ballet troupe of Bombay, and the other is Ravi Shanker playing the sitar, with some musical interpretations by the director. And sandwiched in they wanted me to do any story I liked lasting a few minutes with English dialogue. I didn’t want to do a Bengali film with English dialogue, so I made a film without dialogue involving two children. A rich boy and a poor boy. It’s all 16mm.

And this film you directed in the way you have described with precise control?

Yes, because it was shot in three days, you see; it was done so very quickly I couldn’t tell the boy actors the story or anything. They were asked to do certain things and it was the cutting which made the film. Lots of actions throughout the story, you see, particularly the rich boy. It’s a continuous-time story covering about fifteen minutes, a fifteen-minute long film. One rich boy alone in a big house, birthday party the previous night; he’s got balloons, toys, all sorts of things. At the opening of the film you find the mother just sort of waving as she goes out, and the boy is left alone and then he goes into his room where all the toys are arranged on the shelves, robots and things, mechanical toys which he sort of sets going, and through the window he suddenly sees a very poor boy living in a shack who has his own toys, little things you see, and a musical pipe and a kite. The film is this rivalry between the two, sort of displaying their positions, and finally the poor boy flies his kite—the rich boy hasn’t got a kite, so he’s jealous and he takes what do you call it?—a sling thing, and he tries to bring the kite down, but he misses, but then he’s got a little air-gun and he takes aim and shoots the kite down finally. And then he sets all his mechanical toys going. But his robot walks and tears down the rich boy’s little monument built with toy bricks that has been established previously. And the rich boy can suddenly hear the poor boy playing again his little pipe, you see. So the poor boy is indomitable in a way, that’s the final solution.

And these two boys, as actors, didn’t know at all what the story was?

No. They were told what they were supposed to do, but they didn’t know the import of the story. They didn’t know anything at all, because the two were handled separately. We establish their relation constantly through the juxtaposition of the two, cutting back and forth, you see. When the poor boy was supposed to perform something, dancing with masks on, he wasn’t told that he was doing it for the rich boy, he was just doing it looking in a certain direction. And the rich boy in the same way. I said, “Do this, do that”—I mean just that.

Very often in your films—especially, I think, in Two Daughter—such fleeting emotions pass across the face of a performer, making it very moving, that I think this must have required a real performance by the person. This is not a matter of editing…

Yes, I know, but then I had a very intelligent girl for The Postmaster, the first episode of that film. An amazing girl, only eleven but really wise and understanding, and I could tell her the story. But of course she probably had read it, because it is a very short story by Tagore which everybody knows, you see. Still, there were small things I told her, like, “When you go, look here and look there,” you see. Those things matter, those were all dictated, you see, often very carefully rehearsed in terms of where she was looking, how long she would pause, and those pauses were dictated. That creates the mood, I think, even for the man I was using, although he was a professional actor.

Playing on the intervals.

On the intervals, absolutely, because otherwise the sadness wouldn’t show through.

Are you also a musician?

Well, sort of, now that I’ve been composing. I have to call myself a musician. Music was my first love, before film, even since my school days. Both western and Indian classical music. I’m very conscious of the musical aspect of the cinema.

Do you ever play music on the set to condition the actors, as some directors do?

No, I haven’t done that. Lots of Indian directors do, using sad music to go with sad scenes, to create the mood. But I think the director gets into the mood himself, automatically. I do. You convey it by the manner of your speech and by how you talk to the actors. And if it’s an intelligent actor with a certain modicum of sensibility, he’ll automatically feel it himself. Playing records! I think that’s almost too theatrical! No, sometimes the mood happens without my trying. In Pather Panchali, in the scene where the father returns, and the mother breaks down, it was a terribly gloomy day—raining, raining, raining, and the slush and the light were very somber, you see. It put everything into that mood, and of course everybody felt that this was to be a key scene, everybody was sort of talking in whispers and was keyed up to it. It happened automatically—I didn’t make any efforts to create it.

The performers knew what the scene was to be?

Yes. I tell them when we reach every key sort of traumatic scene of emotion. I try, without imposing too much, to create the atmosphere, by myself not speaking above a certain level.

Do you insist that your crew be quiet on the set?

Yes, I’ve done that, because sometimes a little flippancy on somebody’s part . . . I would sort of ask him not to be.

I’ve seen all of your early films, and I had the feeling that you had made a definite effort to establish a contemplative mood and therefore you were almost not seeking effects through cutting.

This applies to the Apu Trilogy very much, I think, but not to some of the later films. Maharagor is less contemplative because it’s not that kind of a story. I have no set attitude to one particular kind of story. I like to make many kinds of films. This fantasy that I was hoping to make would have been a completely different type of film, with lots of tricks and things of cutting. A lot more mobility perhaps, because it’s not a contemplative story at all.

To sum up your approach: a very, very strong and careful preparation, with a very detailed rehearsal, and a spontaneous result!

Very much careful preparation to get a spontaneous effect. You see, that’s the whole point. You have to prepare for that effect. It can be improvised, off the cuff, or you can prepare carefully and get it. If you’re aiming for an effect all the time, then all your preparation goes toward that, you see. I would perhaps like to improvise a little more if raw stock weren’t such a problem, but you just can’t do that, you can’t afford to. You can’t afford to consciously ruin the man who’s backing you. You owe a certain responsibility to the man. After all, it’s not your own money, and I don’t have a large market. The market is very, very unsure—particularly now, after Pakistan and the west, although I don’t make my films primarily for the west. I have my own audience in mind first, because nobody’s sure ever of the west, now that the Japanese films, even the Japanese films, are not doing so well anymore. The Japanese cinema in New York closed down. No, I must be very sure of what I want when I make a film. Very, very sure. Sure in terms of acting, of set-up, of cutting, of everything.

Earlier Blue interview-articles on the directing of the non-actor, exclusive to FILM COMMENT, have dealt with Jean Rouch, Peter Watkins, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Richard Leacock, and the Maysles brothers.