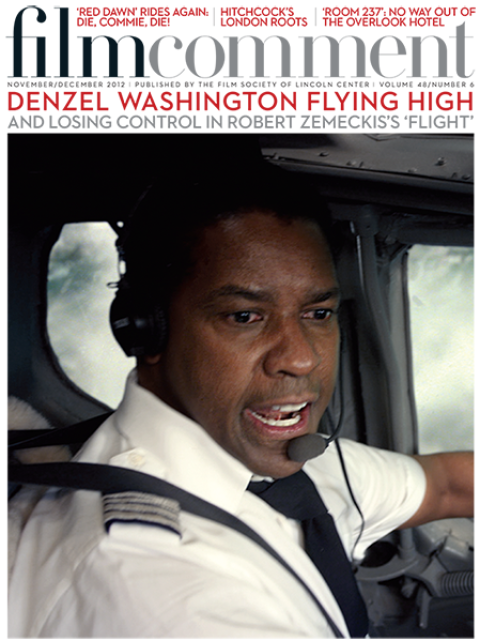

Flight

“God help me,” mutters airline pilot “Whip” Whitaker at the climactic moment of truth in Robert Zemeckis’s Flight. Whip has been hailed as a hero for saving 96 “souls” by crash-landing his crippled plane, having pulled off a daring, decidedly nontextbook aerial maneuver while maintaining the calm professionalism of a heart surgeon. Whip also happens to be an alcoholic and drug user with a messiah complex who’s almost continuously under the influence from the first moment we see him until the film’s final minutes. Like his jetliner, he’s locked into an uncontrolled descent.

The film’s redemption narrative depicting the downward spiral of a self-destructive individual is familiar enough. But what makes Flight a superior version of this narrative is a special effect that tops anything in the terrifying and skillfully directed crash sequence—Denzel Washington’s riveting performance as Whip.

Playing a character for whom lying and self-deception have become almost second nature, Washington gives us, with immense subtlety, the wrenching spectacle of a man who disappoints us without fail. This subtlety is present at every turn, for example in the segue from defensiveness to belligerence when his union rep (Bruce Greenwood) and defense lawyer (Don Cheadle) inform Whip that he may be facing a criminal manslaughter charge after his blood sample tests positive for alcohol and cocaine during the flight. That scene is capped by Whip falling off the wagon in the hotel bar: after slowly turning his double vodka around and around on its place mat Washington downs it in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it acting moment that tells us everything we need to know about misery drinking. And then there’s Washington’s sharp rendition of mortification and shame when Whip attempts, at the funeral of his flight-attendant girlfriend no less, to persuade one of his cabin crew to lie about his condition on the day of the flight.

There’s no apparent calculation and little vanity in this kind of performance. Like any good actor, Washington gives himself the necessary emotional freedom, within the framework of the scene and the dialogue, to find the moments in real time, often with unpredictable results—he’s simultaneously in control and in a state of abandon. At the midpoint of a brief scene in which the intoxicated pilot pays an abortive visit to his ex-wife, careening from aggression through desperation to humiliation in two loaded minutes, there’s a fumbling hug-cum-wrestle between unwelcome father and hostile teenage son that’s simply extraordinary—and perhaps couldn’t have been written. Going well beyond his comfort zone, Washington refrains from explosive grandstanding. With a quietly devastating sense of pathos, he makes Whip’s disintegration and denial almost unbearable to watch.

Integrity. that’s the quality that Washington has most come to embody in his acting across 30-plus years. It lies at the heart of his appeal, and on screen, circumstances permitting, he seems to naturally exude it. We don’t know much about the man behind these performances (nor do we need to), aside from the fact that he’s a committed Christian and the son of a Baptist preacher who in one interview stated that “my work has been my ministry.” That’s an intriguing declaration, since there’s certainly nothing to indicate that he systematically chooses projects that send “positive” messages or strives to be a role model. As it happens, a pronounced Christian motif embellishes Flight’s tale of moral downfall, but the actor is equally at home and just as compelling as a manipulative rogue agent settling scores with the CIA in Safe House (12), Flight’s immediate predecessor in the Washington canon.

Training Day

It’s tempting to conflate Washington’s reliable, casually authoritative screen presence with the man himself. He prefers to shun the spotlight, and professes not to regard his status as a bona fide A-list star as anything more than a label. The only other actor that comes close to embodying the same kind of relaxed confidence, self-possession, and innate strength of character is probably George Clooney, and both have charisma and charm to spare. But unlike Clooney, Washington remains comfortably unglamorous, projecting regularguy at all times. (Interestingly, to his regret, Washington passed on Michael Clayton due to the inexperience of the director.) And while he has plenty of sex appeal (People’s Sexiest Man of 1996), Washington’s characters tend to be settled family men—only a handful of his films feature love interests, and since Spike Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues (90), actual love scenes are few and far between in the actor’s filmography. Also unlike Clooney, Washington has made a great deal of money for the studios over the last 20 years and is therefore, in the eyes of the film industry, a high-value commodity at the top of his game. So far, that’s given Washington the leverage to produce and direct two respectable passion projects, Antwone Fisher (02) and The Great Debaters (07)—albeit with the proviso that he take major roles in each—and made it possible for relatively risky propositions like Flight and American Gangster (i.e., “adult-themed” films) to be green-lit.

Washington’s five-thriller collaboration with the late Tony Scott forms the bedrock of his mainstream success. Is there an underlying pattern to the actor’s buttoned-down submarine executive officer in Crimson Tide (95), death-dealing bodyguard in Man on Fire (04), time-travelling ATF agent in Deja Vu (06), compromised subway dispatcher in The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3 (09), and veteran railroad engineer in Unstoppable (10)? What these characters share, along with the investigative journalist in The Pelican Brief (93), the hustling lawyer in Philadelphia (93), the laid-off factory worker turned private eye in Devil in a Blue Dress (95), the federal agent in The Siege (98), and the police detective in Inside Man (06), is that they’re reassuringly capable professionals—ordinary, flawed individuals who are faced with extraordinary circumstances. As played by Washington, with his instinct to contain rather than externalize, they maintain their cool and don’t make a drama out of a crisis. Self-control is key. As a rule, Washington doesn’t do misfits, mavericks, or loners. In other words, in contrast to someone like Nicolas Cage, he embraces genre material while anchoring it to resolutely level-headed life-sized humanity—no mean feat in today’s Hollywood. That goes double for the traumatized and troubled army officers he’s played in Courage Under Fire (96) and most impressively in The Manchurian Candidate (04); he never goes over the top. (To date, his only venture into mythic larger-than-life heroism is the post-apocalyptic neo-Western The Book of Eli (10), as a lone warrior on a mission to safeguard the last surviving copy of the Holy Bible.)

American Gangster

It’s ironic then, that in his two most iconic and acclaimed roles (Flight should make it a hat trick) Washington plays characters that couldn’t be more at odds with the honest everymen that are his bread and butter. His performance as the eponymous Nation of Islam spokesman and black nationalist in Spike Lee’s milestone biopic Malcolm X (92) resulted in an Academy Award nomination, but it was as corrupt narcotics detective Alonzo Harris in Antoine Fuqua’s Training Day (01) that Washington finally finally won Best Actor. Set over the course of 24 hours, Training Day raised the bar with its depiction of renegade cops as de facto gangsters, and it’s safe to say that Washington’s tour de force as a ruthless streetwise narc completely upended people’s expectations of his capabilities as an actor. A pungent study in hardcore moral turpitude, Washington’s Jekyll-and-Hyde performance is frighteningly believable. In this one-man game of good cop/bad cop, Washington, who has said the part wasn’t difficult to play, gets the joke: Alonzo is giving one long showboating performance from beginning to end. He’s the id inside every actor, running amok, stealing every scene and upstaging his co-stars. But Washington also gives us the fear inside every bully in a meeting with three senior detectives who come off like Mafia kingpins, and, in the film’s penultimate scene, he gives us the weakness inside every strongman in a laughing/crying rant at the inhabitants of a gang-infested hood who’ve finally had their fill of his strong-arming tyranny (shades of The Emperor Jones). Washington even finds room for a fleeting glimpse of Alonzo’s humanity, when he visits his mistress and speaks almost tenderly to a little boy who’s clearly his son—although later he’s perfectly ready to use the child as a human shield.

Washington had a head start when it came to the role of Malcolm X, having played him in the New Federal Theatre’s 1981 production of Laurence Holder’s When the Chickens Came Home to Roost—which is where Spike Lee first saw the actor. Malcolm X’s 202-minute chronicle called for Washington to play the character in several phases beginning with his early years as a small-time criminal and convict, and his performance accumulates ever more gravitas and heft once he emerges from prison and rises to prominence as a minister in the Nation of Islam. Washington is so convincing and authoritative, and so free of strain, that the question of verisimilitude becomes irrelevant. You’re left in no doubt that his Malcolm X is the smartest guy in the room. The actor does full justice to the richly expressive, sometimes almost playful public delivery that was one of Malcolm X’s hallmarks—notice the infectious, delighted smile during the “powder keg” speech—and it’s as if Washington treats these press conferences and sermons as classical performance pieces. Indeed, a handy YouTube side-by-side comparison of Washington and the real Malcolm X making the same speech shows the extent to which the actor made the delivery his own. By the same token he finds moments to offset the man’s public persona: his sigh of relief in the phone booth, after his successful long-distance marriage proposal to Angela Bassett’s Betty Shabazz; or the five-second pause he takes before giving Peter Boyle’s police captain an amused, slightly gloating smile when the cop calls for the protesters to disperse after a tense standoff outside a hospital is defused.

Malcolm X

The ethos of discipline, self-control, and pride that’s embodied in the Nation of Islam scenes in Malcolm X resonates with the self-possession and emotional containment that are so often characteristic of Washington’s screen presence. They’re also echoed in other performances he’s given, the most recent being real-life drug dealer Frank Lucas in Ridley Scott’s American Gangster (07), played by Washington with solemn restraint as a strict and remote figure who operates with locked-down, businesslike professionalism, until, after he’s caught, he relaxes, lowers his defenses, and reveals a disarmingly agreeable man—almost indistinguishable from one of Washington’s good-natured regular guys. In Norman Jewison’s The Hurricane (99), through sheer willpower, wrongfully convicted boxer Rubin Carter moves beyond despair to attain a kind of ascetic transcendentalism that enables him to endure imprisonment and hold onto a sense of personal freedom and dignity. In an appreciative 2002 entry on Washington in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson suggested that Washington “is the first black whose stardom transcends race.” That said, his characters in Training Day and Malcolm X take their place alongside a number of other performances that to a greater or lesser extent foreground a sense of crisis in African-American masculinity, framed in terms of self respect, an inability to accept responsibility, and, once again, self-control. That’s what lies behind the misfortunes that befall Washington’s jazz trumpeter in Mo’ Better Blues (90) and furloughed convict in He Got Game (98)—the latter devastatingly tells his estranged basketball prodigy son: “Get that hatred out your heart boy, or you’re gonna end up just another nigger, like your father.” Self-realization through the instilling of respect is at the core of the Civil War drama Glory (89), in which a disorderly, untrained rabble of African-American volunteers is transformed into a disciplined and formidable fighting force. Standing out from the ensemble (and winning a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award), Washington plays Pvt. Trip, a bully whose contempt for his fellow soldiers masks his own self-loathing.

“The star by right of talent,” Pauline Kael accurately wrote, 25 years ago, of Denzel Washington in Cry Freedom (87), in which he played murdered South African political activist Steve Biko—the first of the real-life civil-rights icons that Washington would play. As written, Biko functions as little more than a tour guide to the iniquities of apartheid, but Washington brings him to life with humor, charm, and undemonstrative moral authority, and when he’s arrested and brutally interrogated, the actor doesn’t make the mistake of playing him as a fearless saint. Hitherto best known as an ensemble player in Norman Jewison’s A Soldier’s Story (85) and the TV medical drama St. Elsewhere (82-88), Washington disappears from the film at the halfway mark. But Cry Freedom, which made a real contribution to the anti-apartheid crusade of the Eighties, clearly announced the advent of a major new actor. Over the 37 films in which he’s appeared in the subsequent 25 years (setting aside his stage work), Washington has quietly but surely advanced to the front ranks, shrewdly avoiding the readily available stock roles reserved for African-American actors—and without ever straining for the false greatness of an “important” performance.

Like I said: integrity.