Endgame

Fed up though we may be, it is of course pie in the sky to imagine a corporate climate in which serious confrontation with topical issues could become a priority. Indeed, leaving aside recent tinderboxes like Fahrenheit 9/11 or Million Dollar Baby, moviegoers still get in line for March of the Penguins rather than Iraq combat doc Occupation: Dreamland, flock to Batman Begins rather than…? Here’s where it gets interesting. Critics have continually argued that in lieu of genuine “problem films” (that long-abandoned post-WWII flurry of liberalism), Hollywood genres smuggle in hot-button political ideas and controversies through the trapdoor of allegory—hence the notion that, for instance, sci-fi charades in War of the Worlds conceal an otherwise unsanctioned message about imperialism. This sort of insight depends on an understanding of ideology as fraught with contradiction, and of genre as a risk-friendly receptacle, but it is at best peripheral to the clamor for “relevance.” Yet even assuming a rough consensus on what it means to produce cogent social dramas, is there an extant model of popular narrative cinema offering unvarnished perspectives on divisive themes?

A logical place to start is the European art film, celebrated at least since the Fifties for its ostensibly deeper engagement with the twin scourges of alienation and neocolonialism. Among other beacons of resistance, pantheon directors Godard, Fassbinder, Antonioni, and Makavejev provided valuable diagnoses of historically specific ills. Unfortunately, that tradition’s pulse-taking cachet has faded, dulled by exercises like Lars von Trier’s potted political cartoons and preoccupied of late with the burdens of multiculturalism—snooze material for a nation built on immigration and slavery. At the risk of echoing jingoistic cant, Americans exist in a post-9/11 universe, while advanced filmmaking in Donald Rumsfeld’s “Old Europe” often appears parochial or, as he delicately put it, “out of step” with the rough beasts that populate our waking nightmares.

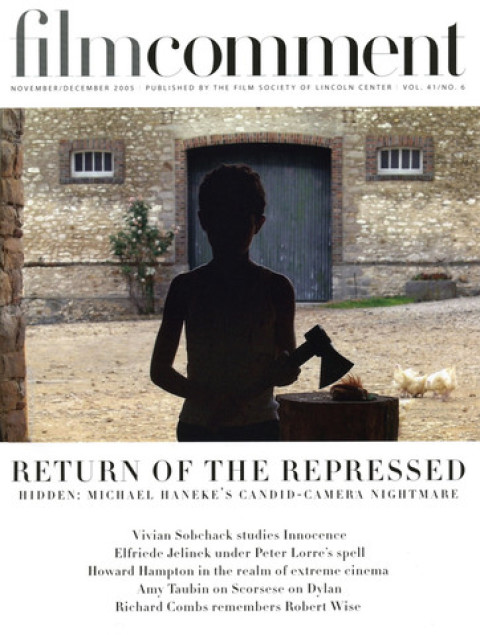

Who then possesses a creative sensibility befitting our contemporary hash of dread, disgust, and rage? Since his first theatrical feature in 1989, The Seventh Continent, German-born Michael Haneke has dispensed post-9/11 visions of violent, benumbed swatches of middle-class society on the brink of dissolution. Four years and numerous debacles after the onset of our apocalyptic era, it is increasingly clear that in our heads—as, for the most part, comfortable, educated, anxious urbanites who also constitute the prime audience for Euro art cinema—we inhabit the same unremittingly bleak, paranoid landscape within which Haneke conducts his nasty business. It is a place we would call home only under duress. Hidden (Caché), his latest and arguably most accomplished provocation, revolves around central characters and a plot predicament that—despite being set in an unnamed French city—feel terrifyingly familiar. That’s the operative word, terrifying. Haneke specializes in what Alexander Horwath labels “boundary transgression” narratives, in which upscale professionals—cushioned from harsh realities by racial and class privilege, as well as by an illusion of control derived from televised news programming—become suddenly vulnerable to hostile outsiders or, alternatively, to subversive acts from within the family circle, frequently committed by children.

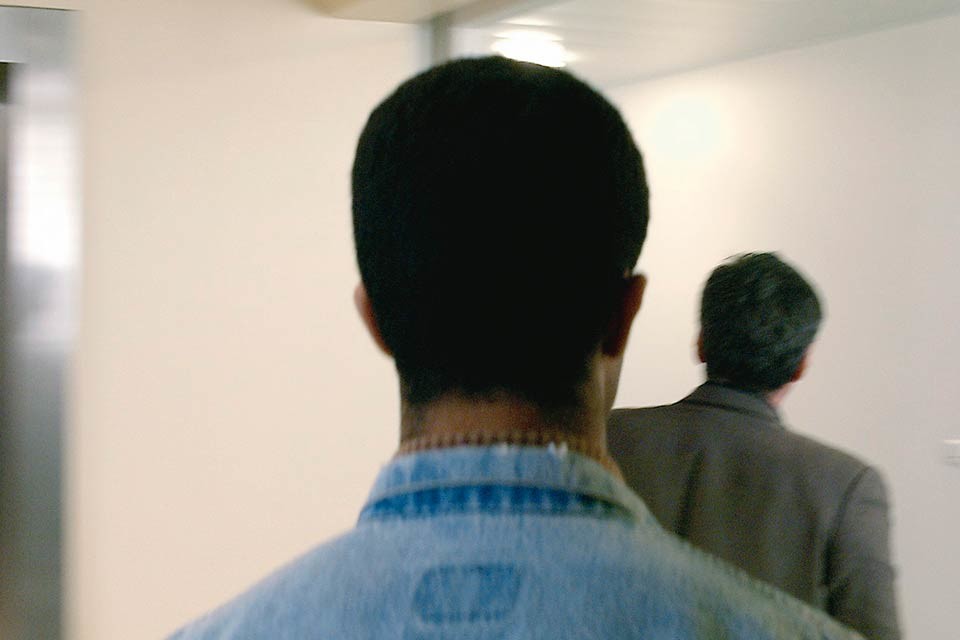

Like the repellently purgative Funny Games (97), Hidden mines an especially timely fable of domestic insecurity: home invasion as the trigger for personal/familial catastrophe. In this case, a pair of seemingly self-satisfied bourgeois bohemians—he hosts a Charlie Rose-type TV literary forum, she’s a book editor— receive a series of unsettling videotapes, at first just surveillance footage of the facade of their luxurious townhouse, accompanied soon after by crudely menacing drawings. As husband Georges (Daniel Auteuil) tries to investigate the source of these threats, his relationships with wife Anne (Juliette Binoche) and preteen son Pierrot (Lester Makedonsky) unravel, in part due to a long-suppressed secret from Georges’s childhood that oozes to the surface. To make matters worse, this revelation—the sketchy betrayal of a young Algerian friend adopted by Georges’s farm-owning parents after an infamous 1961 police massacre of anti-colonial protesters—is matched in disorienting impact by emerging betrayals, sexual and otherwise, perpetrated by Anne and Pierrot.

As usual, Haneke decks out inhospitable family spaces in glinting glass and metallic panels, omnipresent TV screens and rows of videotapes, doorways, and other architectural elements that simultaneously enforce separation and allow for unwanted encroachment. He surveys the disjointed, inconclusive action through a clinical grid of long takes, slow fades, and frontal master shots. Scenes of Georges’s dreams disrupt Hidden’s coolly distanced fabric with an anomalous jolt of subjectivity. In the end, despite an almost throwaway clue, the mystery of who set the fuse that atomizes the family, and why, remains unsolved. As in previous films, the director’s manipulation of genre expectations—a twisting of formula that never stoops to parody or quotation—redirects the hermeneutic energies of the thriller inward toward the protagonist’s flimsy identity and outward to his enveloping social context. The closest analogy would be classic film noir—say, Act of Violence or In a Lonely Place—mediated by the deceptions of the Bush administration instead of the Cold War.

In a move reminiscent of several Haneke films in which a scene is replayed on video, it pays to quickly rewind his career leading up to Hidden. The son of professional actors, he studied philosophy at the University of Vienna, and wrote and directed plays before logging a 15-year stint in commercial television, a medium repeatedly excoriated in his features as a desensitizing purveyor of violence. The opening chapter in his “trilogy of emotional glaciation,” The Seventh Continent, is loosely based on a real case, a common source for Haneke’s deadpan tabloid scripts. Understated to a fault, the film hovers over the silences and miscommunications in a household of bourgeois automatons who calmly decide to commit suicide, although not before smashing their worldly possessions to bits and flushing wads of money down the toilet. In Benny’s Video (92), a pampered teenage boy obsessed with footage he shot of a hog being killed with a stun gun on his parents’ weekend farm invites a disaffected girl to the family apartment, then kills her with the purloined weapon, only to have pragmatic Dad cover up the crime. 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (94) exudes more urban anomie and senseless murder, this time through a stark calculus of four separate stories of unfulfilled need, shards of which overlap during a shooting spree in a bank.

Haneke essentially tells two kinds of stories: chamber pieces that implode around a family triad—what the director dubs the “germinating cell for all conflicts”—and more expansive medleys involving socially disparate ensembles. They are distinctly urban, and distinctly European in texture. Moreover, the traditional Romantic remedy for estrangements of urban society, the pastoral sojourn, has long ceased to be an option. Nature is governed by brute Darwinian imperatives realized in motifs of dead livestock and desiccated forests. One of his few non-urban endgames, The Time of the Wolf (03), rehearses the dog-eat-dog aftermath of an unspecified national crisis suggestive perhaps of a massive terror attack. When an ineffectual paterfamilias is gunned down by an intruder in a rustic vacation cabin, Mom and two kids scavenge the countryside until they arrive at an improvised refugee center whose social dynamics resemble a Holocaust concentration camp; A Day in the Country it is not.

As is true with brand-name auteurs on both sides of the ocean, Hanekeland is filled with signature stylistic gestures, iconography, and thematic ploys. To be sure, each film nurtures its own discrete episodes and trajectories; given how thoroughly Haneke eschews behavioral explanations—forget Freud—there is surprisingly little cross-textual redundancy of character. That said, an almost Hitchcockian bounty of small obsessions (think chicken dinners) lends the oeuvre a dense personal tapestry: solitary women crying; people determined to sleep in the midst of upheaval; people named Anna and Georges; secondary characters with the surname “Schober” (a historical figure drawn from the messy life of Haneke’s beloved Schubert); mechanized rituals such as eating or tooth-brushing; supermarkets; reality TV footage as domestic wallpaper; letters spoken in voiceover; fences that occlude entrances to buildings; classical music; darkened bedrooms; pitch-black exteriors; vomit; self-inflicted wounds; blood seeping slowly from beneath inert bodies.

By the same token, no map of Haneke’s grim territory would be complete without mentioning its emotional ecology, predicaments replayed with slight variations, by which individual tales unfold. Latchkey children are primed to turn feral, or worse, given the opportunity. Chance meetings in public places fuel unforeseen narrative detours but rarely result in illumination for their harried participants or for us. Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle is by now thoroughly internalized. While speed is never a determining factor, auditory leaps from loud to soft—or, as a masochistic woman in The Piano Teacher (01) articulates Schubert’s tonal range,“from a scream to a whisper”—puncture an otherwise laid-back formal syntax. Since knowledge is always less absolute than situational, it is hard to take sides in heated cross-cultural skirmishes around gender or race—a stance that resembles but ultimately rejects postmodern skepticism. Domestic security is a mirage, like empathy or filmic subjectivity.

The withholding of crucial narrative information, including flagrant use of ellipses, becomes the formal embodiment of a reluctant ethics framed largely through negation. According to Haneke, his films are intended as “polemical statements against the [unthinking] American cinema and its disempowerment of the spectator.” In place of what he sees as simplistic explanations, a “clarifying distance” will transform the viewer from “simple consumer” to active evaluator: “The more radically answers are denied to him, the more likely he is to find his own.” In truth, this prescription for battling psychic evils associated with the Hollywood system—slow the pacing, deny subjective identification, refuse to tie up loose ends—has had numerous proponents; at times Haneke sounds like an anti-humanist version of André Bazin, champion of long-take perceptual ambiguity as practiced by Renoir, Welles, Bresson, et al.

It is no accident that Haneke refers to Bresson as his “idol,” or that he cites Antonioni’s urban anatomies as inspiration. Kubrick’s morbid detachment and paranoid outlook on technology spark additional comparisons (as homage, The Piano Teacher uses the Schubert piano trio featured in Barry Lyndon). Indeed, an abiding paradox in Haneke’s work is that its hermeticism can also foster copious links or affinities with wider artistic practices, especially those of postwar Germanic culture. Yes, Fassbinder’s Why Does Herr R. Run Amok? looms as godfather to Haneke’s early trilogy, but so do several of the Straub-Huillet literary adaptations. There are intriguing convergences with documentary essays by Harun Farocki, in particular his caustic 1990 rendering of mechanized learning in How to Live in the German Federal Republic. The flat affect Haneke adopts for even the most outrageous activities has a literary pedigree that extends from Kafka—whose novel The Castle was filmed by the director in 1997—to Heinrich Böll and Peter Handke. In the visual arts, Gerhard Richter’s expressionless paintings of the Baader-Meinhof gang resonate with several films, and the treatment of urban exteriors in Hidden and Code Unknown (00) recalls the huge architectural photo studies of Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky.

The crux of the problem in Hidden, as it often is in the work of Haneke’s artistic soul mates, revolves around questions of control, of power and emotional manipulation—more precisely, who is behind the surveillance tapes and what was their motive in making and sending them. Imagine the scenario of Rear Window re-presented from the perspective of wife-murderer Thorwald rather than voyeur-sleuth L.B. Jeffries (minus the resolution, of course). Except in this case the plaintive cry delivered by Thorwald when he enters the lair of his eager tormentor—“What do you want of me?”—is delivered by guilt-ridden investigator Georges to a hapless victim, when it should be directed inward at the deceptions propping up his fatuous sense of self. Once again, this is typical film noir turf implanted with the fleurs du mal of contemporary crisis. We feel insecure, stressed, threatened by elusive forces whose connection to us as individuals is obscure. Yet we can’t quite shake rumbles of complicity, of having acceded to something for which we will ultimately be held accountable and from which our unprecedented standard of living cannot protect us. It is this heart of darkness that beats beneath the icy surface of Haneke’s films. An unwelcoming site, we avoid it at our peril.