Magic Touch: The Eyes of Orson Welles and The Mystery of Picasso

“You were mad for contact with the world,” director Mark Cousins says, addressing the subject of his film The Eyes of Orson Welles. And we are mad for contact with him, for some way to get inside his head, see through his eyes, fathom his astronomically vast but maddeningly messy gifts. We want to get under his skin the way he has gotten under ours. But how can we? In 1956, Henri-Georges Clouzot suggested an answer, stating in the prologue to his astonishing film The Mystery of Picasso that “to understand a painter’s mind, one need only follow his hand.” Cousins takes a similar tack, building a portrait of Welles around the drawings and paintings he made throughout his life. Sketches, doodles, handmade Christmas cards, finished paintings emerge from archival storage boxes and fill the screen. Occasionally they appear through animation, as though an invisible hand were creating them on the spot. Drawings are direct traces of physical contact and movement—what someone saw and how they translated it through their body into a permanent image. Bringing together Welles’s artworks and his films reveals their similarity; both, in their visceral expressiveness, their stylization, their physicality, let us follow his eye and his hand.

The chance to see these artworks would make The Eyes of Orson Welles required viewing even if it were not for the lively intelligence with which Cousins shapes his investigation of Welles as a political activist, an adventurous traveler, an “omnivorous” lover, a satirist, an elegist. The result is more of an essay film than a documentary, built around thematic chapters woven together by the director’s very personal narration, delivered in a charming Scots-Irish brogue. This structure allows Welles to appear in all his contradictions: an ardent sympathizer with the marginalized and persecuted who was also endlessly fascinated by tyrants and tycoons; a quixotic lover of lost edens who was forever moving on and leaving things behind. (“You wanted to be Falstaff, but let’s face it, you were Hal,” Cousins says in one of his sharpest observations.) The actress Geraldine Fitzgerald, one of Welles’s many lovers, summed him up when she compared him to a lighthouse, utterly dazzling when his beam shone on you, then plunging you into darkness when the beam passed on. Like a steadily revolving light, one image of Welles keeps returning to the screen: a photograph in which he sprawls across a bed, his huge saucer-like eyes gazing straight at us, expressionless, his mouth slightly open. It is not an especially flattering picture, but it shows the great performer and showman as a watcher and listener, wide open, insatiable. In his narration, Cousins addresses Welles in the second person, with a stream of questions and rhapsodies and provocations. At one point, he imagines his beloved responding, with actor Jack Klaff channeling Welles’s sonorous growl.

That Orson Welles was, on top of everything else, a prodigiously talented artist is just one of those cosmic inequities. His sketches of passengers on the boat he took to Ireland as a teenager, and of people he saw in Morocco not long after, are gracefully economical in their use of line to suggest form and gesture. “A line is a dot that goes for a walk” is attributed to the artist Paul Klee; Cousins repeatedly uses this image of “taking a line for a walk” to convey the exploratory nature of sketching, the pencil moving through space without a fixed route or goal. The word “sketchy” can mean vague, incomplete, untrustworthy, even risky. But sketchiness could also mean immediacy and intensity of focus; a sketch is fresh, the start of something, imperfect in the literal sense of unfinished. Welles, as time went on, produced less and less finished work, but everything he touched had the flair and character of an inspired doodle.

Chimes of Midnight (Orson Welles, 1965)

Looking at Welles’s movies through his artworks, Cousins—the director of the mini-series The Story of Film: An Odyssey (2011)—tosses off eloquently concise insights into his visual style: the way his preference for wide-angle camera lenses makes the world “bulge,” his love of actors “swirling,” especially through labyrinthine spaces like the tavern in Chimes at Midnight (1965) or the arcades of Los Robles in Touch of Evil (1958). The Shakespeare films (Macbeth, Othello, Chimes at Midnight) reveal their likeness to charcoal drawings—thick-lined, shadowy, tactile, making up in style and intensity what they lack in precision. Welles’s use of low-angle shots is no news, but when Cousins calls him “the greatest filmmaker of looking up,” the phrase captures an essential quality that unites the look, the themes, and the feel of his movies, the way his bulging, swirling world looms above us, always threatening to topple under its own weight.

If Welles was the greatest filmmaker of looking up, he was also one of the greatest filmmakers of looking back. He said in an interview that every artist ought to feel out of his time. Yet it remains an enduring mystery how and why a prodigy in his mid-twenties and on top of the world brought forth two of the best films (Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons) ever made about aging and its cruelest side effect: the inconsolable sense of loss, regret, and waste. Irresistibly drawn to the pathos of the old, he aged himself with makeup to play Charles Foster Kane entombed in his mausoleum of a mansion; the bloated wreck of Sheriff Hank Quinlan following the sound of a player-piano to Tanya’s lost-in-time bordello; Falstaff rejected by the newly crowned King Henry V (“I know thee not, old man”). When the middle-aged Isabel Amberson Minafer (Dolores Costello) sits in her parlor at twilight, knowing she cannot repair her life by reuniting with the man she should have married, it looks like all of the light is slowly draining out of the world. Throughout The Eyes of Orson Welles, Cousins makes then-and-now comparisons of places where Welles lived, worked or traveled, many changed beyond recognition, a few, like the Irish countryside, unaltered. He suggests that the world in the 21st century has become “more Wellesian”: hyper-visual, overstimulated, grotesquely exaggerated, and ever more in thrall to frauds and tyrants. Ever more nostalgic too, perhaps, because so much of the past can now be seen and heard, but it is no less gone for all that.

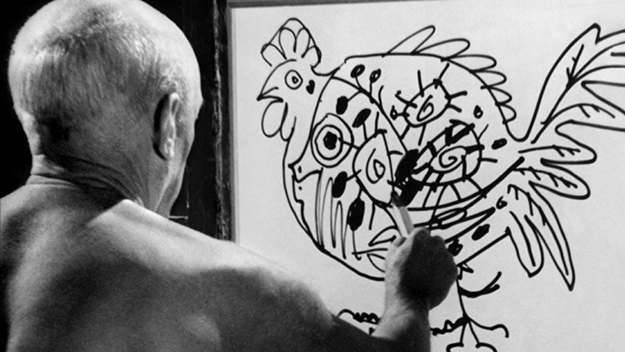

In The Mystery of Picasso, Clouzot filmed the artist in the act of creation; most of the works he made on screen were destroyed afterwards, leaving only their images on film. Clouzot and Picasso collaborated to devise a new method, shooting from the back side of a translucent canvas on which Picasso drew and painted with inks, so the lines and washes of color seem to appear by themselves on the screen. A dot goes for a walk, skips and hops and dances a jig; colors bleed and run and eat up space. Sometimes the only sound is the squeak of a marker, the lines talking to themselves as they spring to life; at other times, they are set to music (by Georges Auric): bright trumpet fanfares, flamenco guitars for drawings of bulls and matadors, thumping drums for abstract cubist patterns. After a series of these animated vignettes of pictures coming into being, Clouzot gives away the secret of how it is done, revealing the canvas, the lights and camera, the crew, and the seventy-something Picasso, shirtless, calm, with a dark-eyed gaze that bores holes in the screen. The entr’acte plays as deadpan comedy, the master painting against the clock—or rather than footage meter—as the cameraman runs out of film. The richly graded, sharp and lustrous black and white of this sequence contrasts beautifully with the bright colors and scratchy, fuzzy lines of the artworks (especially in a pristine new 4K restoration, screened at Film Forum in March).

So, what do we learn from getting inside the mind of the painter? That he worked in layers, or—as he puts it—in stages. He does not rough out an overall design, he does not start with a loose sketch and add detail, like the amateur. He just touches his pen or brush to the canvas and the drawing sprouts and spreads like a vine from a magic bean. Somewhere along the way, a pair of woman’s breasts will appear, often ogled by a short, fat, ugly man. (In F for Fake [1973], Orson Welles concocted an elaborate hoax about the elderly, lecherous Picasso painting the nude Oja Kodar.) Once he has a complete, delicate drawing, he often swamps it with dark shadows or shapeless colors. He has second thoughts. He draws a fish, then turns it into a chicken, then at the last moment turns it into a face.

“We haven’t gone below the surface yet,” Picasso says halfway through the film. “We should go deeper.”

So, in the second half, Clouzot turns to a different technique, using stop-motion to present the development of oil paintings, through layers and erasures and revisions, compressing into a few minutes a five-hour struggle. “When looking at any significant work of art,” Paul Klee wrote in his diary in 1904, “Remember that a more significant one probably has had to be sacrificed.”

The climax of The Mystery of Picasso is an epic battle over a light-hearted beach scene centering on a girl in a bikini: a tragi-comedy of obsessive overworking. (“It’s going badly. Very badly,” Picasso remarks placidly.) Day turns to night, heads are endlessly erased and replaced, strange mythical figures appear, disappear, reappear. The painter murders his darlings. Only an artist with enormous self-confidence, and an odd kind of humility, would let us see him work this way. In the noir thrillers for which he is best known—Le Corbeau, Les Diaboliques, Wages of Fear—Clouzot dazzlingly revealed humanity at its worst. Here, cinema’s great misanthrope shows Man at his best: playful, inventive, unselfconscious, indefatigable.

“Genius,” to quote Klee one more time, is “the error in the system.”

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, and has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere. Phantom Light is her regular column for Film Comment.