Film of the Week: What Will People Say

What Will People Say, the second feature by Iram Haq (I Am Yours), is based on the Norwegian director’s own experience: at the age of 14, she was kidnapped by her own parents and forced to live for a year and a half in Pakistan. Given her film’s traumatic inspiration, it might seem surprising that the result comes across on-screen as a little impersonal—yet, that makes a kind of sense. The film isn’t just Haq’s story, nor that of 16-year-old Nisha (Maria Mozhdah); it’s the story of Nishas all over the world—girls from Islamic families caught between the modern secular societies to which their parents have migrated and the old traditional values. What Will People Say suffers a little from feeling like a film expressly designed to trigger urgent post-screening debates, but it’s a forceful and moving piece that has more nuances than its intense drama ostensibly conveys.

Nisha, the daughter of Pakistani immigrants to Norway, is first seen living a secret after-hours life as an Oslo teenager—running home after an evening with friends to sneak into her family’s apartment unnoticed by father Mirza (Adil Hussain), as he does his late night rounds, checking that everyone’s tucked in bed. Nisha loves hanging out with a mixed-race, mixed-gender crowd, playing ball, dancing, enjoying an after-school joint—but her secular self has to be rather more discreet than she’s always able to manage. At a family party, Nisha texts friends on the sly, and it’s a wonder that her parents don’t respond to her phone’s telltale pings (or the suspended text messages that Haq places floating around the screen).

The film grants Nisha one brief first-act moment of rapture: she dances at a club in slo-mo, a deep sonic boom ominously enveloping her before the music cuts in. It’s rather more euphoric than the tentative romantic moment that comes soon after, an altogether chaste moment of intimacy with high school boyfriend Daniel, who has climbed with her through her bedroom window. “Have you asked my parents if you can marry me?” she joke—but neither of them have taken the family’s sense of propriety seriously enough. A moment later, a shocked Mirza walks in on them and beats the living daylights out of the boy.

Facing social workers after, Nisha shows that—as is often naturally the case with adolescents—the spirit of rebellion only goes so far. Rather than feel rage, her first response is, “I shouldn’t have done that.” One of the social workers calmly assures her, “Once your father and you have had a chance to talk, everything should be fine”—perhaps the heaviest touch of irony in the film. Mirza turns up with a list of demands, notably that Nisha must marry Daniel; flying off the handle, he doesn’t believe for a second that Nisha hasn’t slept with the boy, but by the criteria he’s using, a shy kiss is tantamount to orgiastic libertinage.

The film is most interesting when illustrating its title: the agony for Nisha’s parents is not just that she has ceased to play the proper role of a chaste daughter, but that her actions, such as they are, threaten to make them pariahs in their community. People have stopped coming to the family shop; later, Nisha’s mother, Najma (Ekavali Khanna), complains that they’re no longer being invited to weddings. Fathers in the community insist that Nisha be punished, lest her bad example set off an epidemic of youthful impropriety. The parents’ need to conform is sketched in with some sensitivity: we understand they’ve struggled hard to establish themselves in a new country. Then comes the capper, which adolescents hear from disapproving parents in every culture, every day of the year: it was all for the children’s sake, “and you do this to us.”

The film takes a turn towards grim thriller after Najma tells her daughter she can leave the shelter where she’s permanently staying: all will be well. Nisha believes her and eagerly steps out, but doesn’t understand why Mirza and his son Asif are taking her for a drive. There’s some bleak humor in this sequence: while Nisha is ordered to shut up and sit quietly, the men chat blithely about cars. She makes a run for it; Asif grabs her and drags her back to her car. Could this happen to a young woman in broad daylight, with no-one intervening? Haq doesn’t let you doubt for a moment that it can, and does.

Cut abruptly to Pakistan, where Nisha and Mirza are welcomed by family members in Islamabad. She’s fussed over: her cousin, a younger girl, wants to know if she prefers Beyoncé or Rihanna. She’s drolly warned against mosquitos: “They’ll suck out your European blood. You’re an imported delicacy.” But it’s clear that Nisha is in prison, and knows it. She makes a desperate attempt to get online, is caught and locked up, her passport burned. Now, says her uncle, “you are our daughter.”

Eight months later, Nisha seems to have become the model Pakistani daughter, meek and serious at school, in blue and white uniform with headscarf, calmly ignoring her female classmates’ innuendoes. At this point in the film, we don’t really know what’s going through her mind: it’s a subtle touch on Haq’s part to distance us from the Nisha we’ve seen earlier. She seems to have embraced the ways of Pakistani courtship: she and her dashing male Amir have fallen for each other, and close-ups show their fingers coyly interlinked as they walk through the market. One night, they go into the city to find a quiet place to bill and coo—nothing remotely torrid, though Nadim Carlsen’s camerawork, hovering close on Nisha, captures her in a traditionally romantic languor. That’s when things go horribly wrong, as both Nisha and Amir are suddenly submitted to a violent form of humiliation from an unexpected quarter—the film’s most unnerving moment.

This episode, in fact, is a lot more troubling than the climactic moment of truth between Nisha and her father when he returns to Pakistan to confront her. It’s clear that they’ve now both become the despair of her family—the daughter and the father who can’t keep her in line. The life-and-death cliff-top confrontation that follows isn’t entirely convincing. Does Mirza really want her to jump? Would he really push her if she didn’t? It perhaps makes most sense as a melodramatic acting out of the fact that both of them appear to have reached the end of their respective lines: both are on the edges of their own abysses.

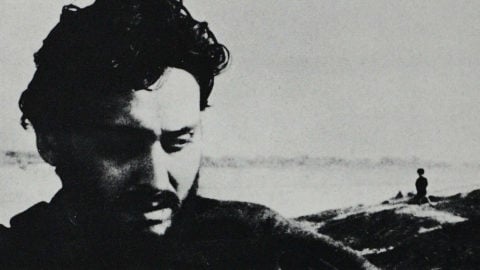

Maria Mozhdah is extremely good as Nisha, her heavy-browed, stark beauty fitting perfectly both as the exuberant Western teenager and the introverted maiden that she seems to become. The surprise that the film successfully manages off is that, having at the start established Nisha as a rebel—albeit a cautious one—it doesn’t insist on her fighting all the way through. Instead, it shows the effect of fear, the instinct of self-preservation, and indeed her respect for her parents and the culture she’s been raised in: a potent combination that no Nisha could work through overnight.

What also gives some nuance to what might have been a schematic drama is that everything isn’t laid at the feet of a repressive patriarchy: it shows the family itself as a repressive institution. (This is hardly an exclusively Islamic theme: the motif of daughters imprisoned by their religious families is a staple of early 19th-century European Gothic fiction, where cell doors are forever slamming shut on girls destined for convents). Haq doesn’t only identify Mirza, his male friends, and relatives as the oppressors, but shows women’s part in the process: the aunt in Islamabad and Najma, who—perhaps most damningly—reassuringly lures her daughter back to the fold so that she can be punished.

As for Mirza, he’s given a softer, gentler focus that makes him more vulnerable: his delight in dancing at a party to his favorite song (something his wife thinks is utterly inappropriate) or, having dragged his daughter forcibly across two continents, clumsily attempting to show his love by offering her chocolate cookies. As Mirza, Adil Hussain has a thoughtful, delicate demeanor that contrasts with the punishing rage—and his most telling moment is the rueful look Mirza gives as he realizes that the fate that’s being put in place for Nisha isn’t quite what he would have wanted for her—one that would have involved a little more self-determination and status.

The film is good on specifics, on little cultural details that you assume come from Haq’s own experience: whether it’s the pleasure of being young and hanging out in the Oslo snow, or the bickering between her uncle and his ancient mother-in-law, or her uncle’s threat of a rural marriage if she misbehaves: one false step and “you’ll be milking buffalos for the rest of your life.” Such touches make something a little more distinctive of a film that’s tough and clearly from the heart, but that at times feels closer than Haq likely intended to being an impersonal headline-news melodrama.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.