The Lives of Others

It is certain that neither men nor women are clearly defined personalities but rather vibrations, flows, schizzes and ‘knots.’ —Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus

“It may be true that one has to choose between ethics and aesthetics, but it is no less true that whichever one chooses, one will always find the other at the end of the road.” —Jean-Luc Godard

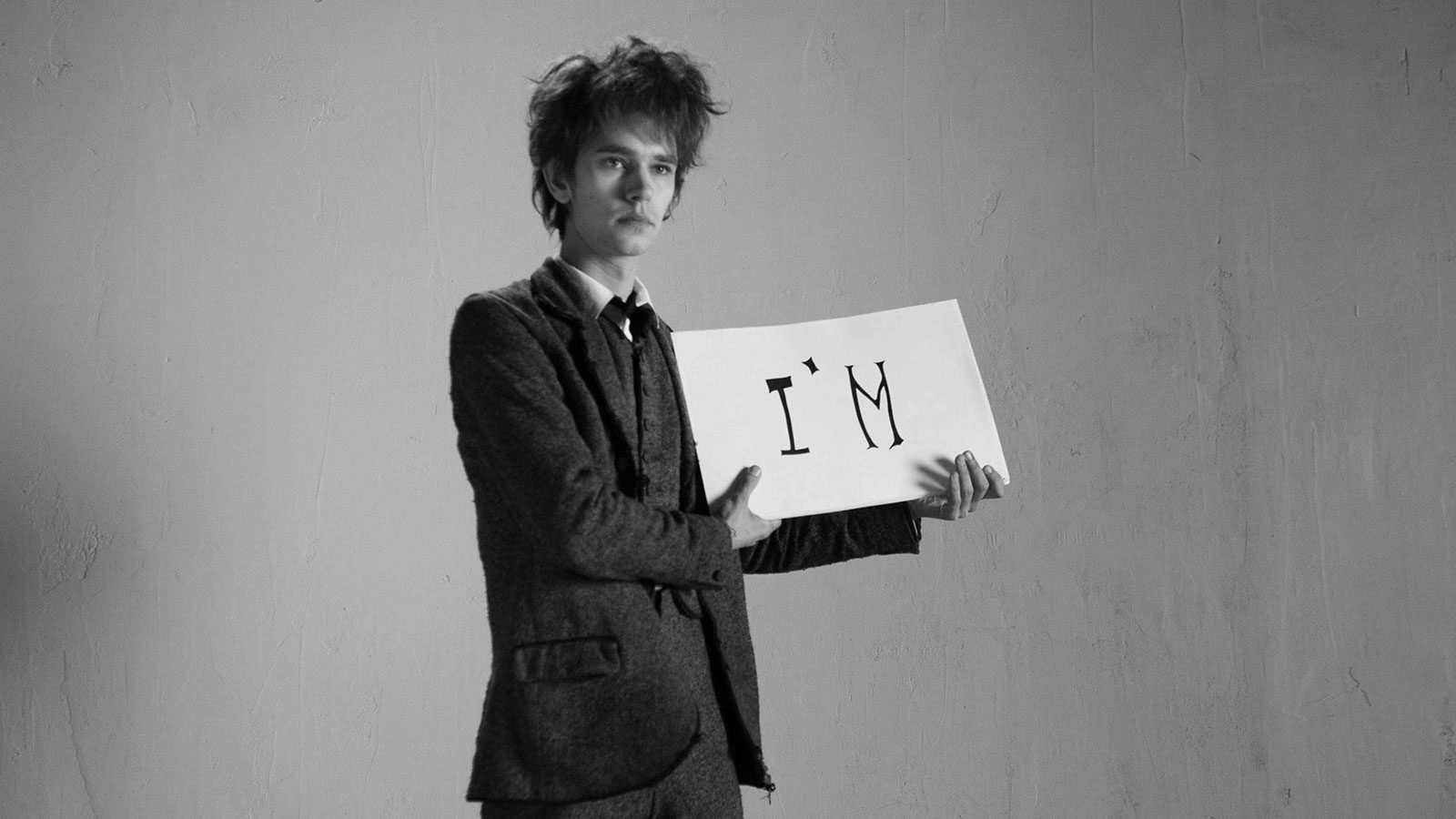

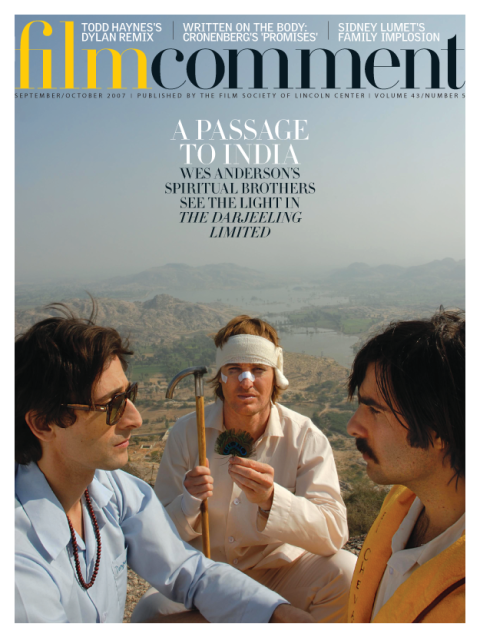

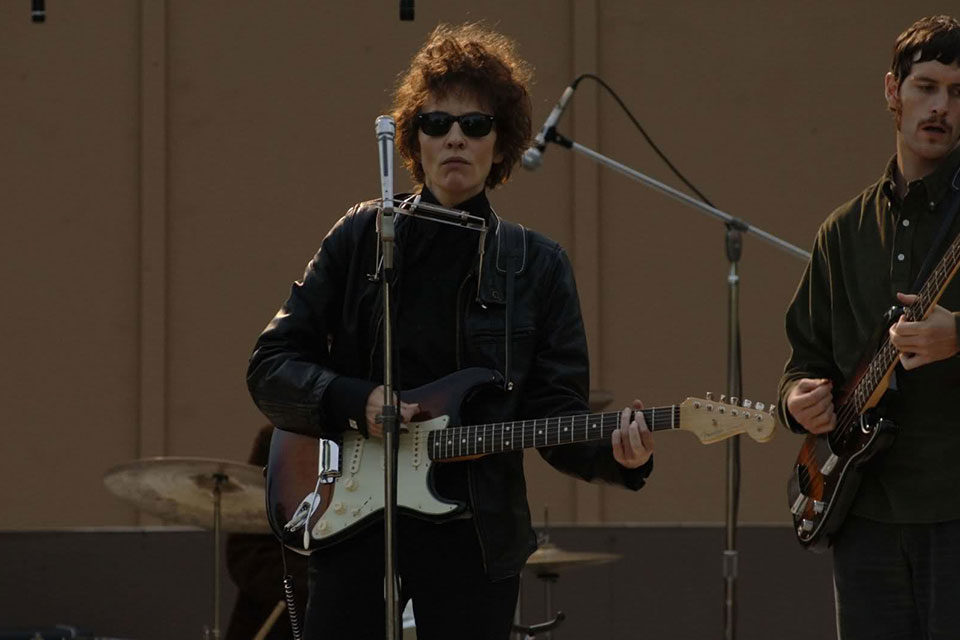

Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There is an essay-poem on the myth and history surrounding the career and music of Bob Dylan. Allusively complex, it’s also a Finnegans Wake–like meditation on Sixties film culture. Haynes’s references to films like Masculin-Féminin, Petulia, A Hard Day’s Night, 8 1/2, and Darling are not film-historical erudition for its own sake but serve to underscore that Sixties cinema was always already influencing the cultural-political reality from which Dylan sprang. Rather than one more recitation of biographical anecdote, Haynes’s conceit is the construction of a kind of ur-Dylan substance that is drastically collective, a-chronological, and non-psychological. Six Dylan alter egos circulate through the film: Cate Blanchett and Christian Bale are the nearest-to-literal incarnations, with Richard Gere as a mix of Dylan and Billy the Kid, Ben Whishaw as Dylan by way of Rimbaud, and Marcus Franklin, a 10-year-old African-American, embodying Dylan inhabiting the persona of Woody Guthrie. Finally, Heath Ledger plays a movie star haunted by the experience of having recently played “Dylan” in a film within the film. Haynes has previously tried constructing Chinese boxes of allusion, quotation, and pastiche in Superstar and Velvet Goldmine but he masters this strategy in I’m Not There. The film’s thematic center of gravity is the tragicomic success-and-failure of Dylan as a political prophet.

I’m Not There says, among other things, that the presence of politics in works of art, like the presence of the artist’s personality, is at once unavoidable and virtually inexpressible. The audacity, beauty, and complexity of Haynes’s ironic celebration-and-critique are, quite literally, unlike anything you’ve ever seen before. Incidentally, the music’s cool, too.

It’s a strange business,” says French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, “speaking for yourself, in your own name, because it doesn’t at all come with seeing yourself as an ego or a person or a subject. Individuals find a real name for themselves, rather, only through the harshest exercise in depersonalization, by opening themselves up to the multiplicities everywhere within them, to the intensities running through them . . . It’s depersonalization through love rather than subjection . . . We have to counter people who think ‘I’m this, I’m that’ . . . by thinking in strange, fluid unusual terms . . . Arguments from one’s own privileged experience are bad and reactionary arguments.”

Of course, the earliest, most memorably succinct formulation of this idea—the demolition of a stable, coherent, metaphysically grounded self—came from the 19th-century French poet who inspired Dylan and whom Haynes invokes early on in I’m Not There, Arthur Rimbaud: “Je est un autre” (“I is an other”). At the most literal level I’m Not There is not a biopic about Dylan, whose name is never mentioned in the film and whose “real” image only appears once at the end. Haynes isn’t interested in supplying a convincing representation of the events of Dylan’s life, nor some conclusive, coherent, emotionally rewarding interpretation of those events.

Yet at the same time, Dylan is everywhere in this film—as its inspiration, as its limit point, as its condition of possibility. The film’s dialogue probably contains more of Dylan’s actual words than we’ve ever heard before at one time. That’s because Haynes is more interested in what Dylan has created than in what his life has been like. (Indeed, it’s arguable that this ironic dichotomy has been a chief characteristic of that life. When Proust says, “A book is the product of a different self from the one we manifest in our habits, in our social life, in our vices,” he is implying that the “different self” who writes a book is the truer one.) But the panoply of quotations also suggests that there is a strong “documentary” component to Haynes’s radically artificial assemblage.

Six actors play Dylan. Is that right? Not quite. Since none are explicitly identified as Dylan, a different designation is required. Call them avatars, in honor of our era of Internet gaming.

These six Dylan avatars mix and match qualities, and Haynes constructs a way for each to embody not-Dylan from a fresh angle, with a different degree and distance from the literal source. Guthrie, Rimbaud, and Billy the Kid are personas Dylan adopted and they slip, relatively briefly, in and out of the film’s structure. Christian Bale’s Jack Rollins conveys the idea of Dylan most trapped and banalized by liberal political commentary (in this section Julianne Moore is quietly hilarious, evoking the commodification of Sixties political nostalgia by “doing” Joan Baez in more ways than one) and later by evangelical Christianity. Cate Blanchett’s Jude Griffin suggests the Dylan of Don’t Look Back through Blonde on Blonde, that is, Dylan when he almost perfected his persona, image, and voice. She is given his most memorable lines. And yet the change of gender renders her distance from literal truth uniquely extreme.

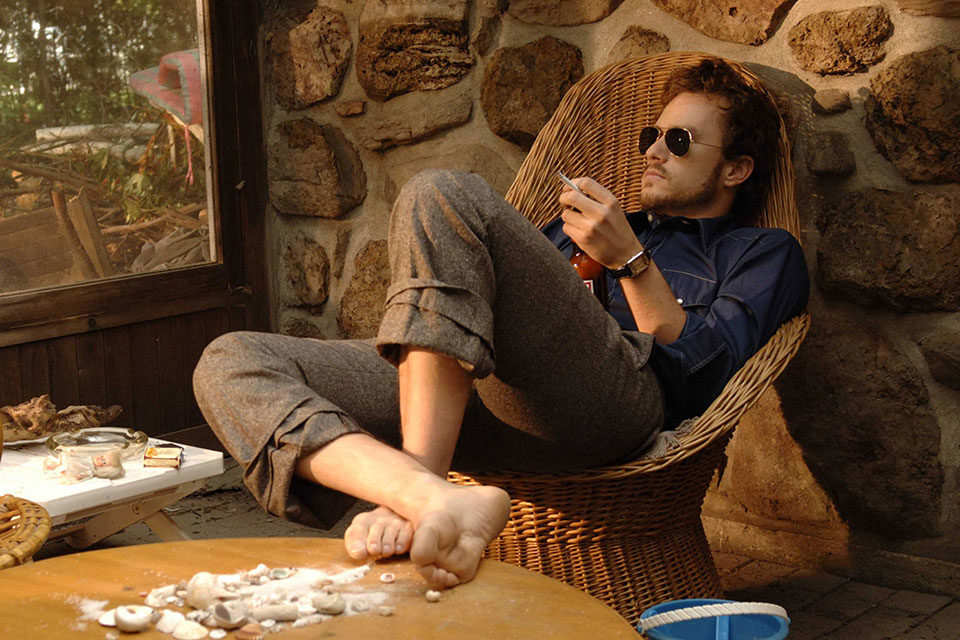

Heath Ledger, as an actor whose life is transformed after he plays Jack Rollins, is the simulacrum of Dylan—a fictional actor playing a fictional alternative version of a real person. Paradoxically, it is in his story that Haynes comes closest to showing details from the “true story” of Dylan’s existence, his unsettled love life, and ultimately unsuccessful attempt at marriage and family. In this section, he also employs Charlotte Gainsbourg as an inspired fusion/assemblage of Suze Rotolo—Haynes restages the famous photo of her and Dylan on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan—and Sarah Dylan.

It would be tempting to describe I’m Not There as being about six conflicting interpretations of Dylan, another Rashomon, another variant on Citizen Kane (a film that provided the structural template for Velvet Goldmine, Haynes’s first shot at devising the method for this film). Tempting to see it as one more contribution to the modernist canon dealing with the relativity of perspective, the anxiety of representing a Self. Tempting but ultimately misleading.

The film, though never quite upbeat, is urgent, energetic, embodying a newer, more open, more plural, and therefore affirmative kind of thought about identity. Because Haynes is more concerned with a certain Dylan-ness, or Dylan effect, and because Dylan-the-text matters more than Dylan-the-person, there is a prevailing grace and lightness of tone. Older, realistic, anecdotal, pathos-driven narrative structures aren’t merely critiqued or deconstructed. They’re bypassed, ignored. They’re surpassed.

Three artists were the apotheosis of what we still feel compelled to call the Sixties: Dylan, Warhol, and Godard. Each enacted the depersonalized singularity that Deleuze describes. Warhol—the point of intersection between high modernism, self-fashioning gay sexuality, and the awareness of media technology in art, and moreover the great contemporary reincarnation of Oscar Wilde—has at all times been in Haynes’s aesthetic DNA.

Is a cinematic poem of ideas possible? A film organized by concepts and argument that also manages to be entertaining and fun? One significant contemporary, whose concerns and practices overlapped with those of Dylan, thought so. In I’m Not There the director uses Dylan partly to conduct a conversation with Jean-Luc Godard. This is suggested from the outset: I’m Not There opens and closes with offscreen gunshots much like those that begin and end Masculin-Féminin, Godard’s most concerted effort to intervene in Sixties youth culture in its pop-music aspect (“the children of Marx and Coca-Cola”) and incidentally the only major film of the period to name-check Dylan. Casting Gainsbourg, a French actress, as the avatar of Dylan’s most serious love objects, obliquely suggests an overlap between Godard’s passions and Dylan’s: a dark (Anglo-) French gamine, she evokes Anna Karina, Godard’s muse, not to mention her own parents, Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin, French pop-culture icons and contemporaries of Dylan.

But besides these clues, there’s the film’s commitment to devices from the Godard playbook: pastiche, allusion, quotation, the use of actors to construct allegorical or phantasmatic images of people rather than plausibly represent or incarnate them, the utilization of stars not purely to recruit audiences but to inspire reflection on the multiplicity of identity and the illusion of a coherent self. Godard pioneered the use of these strategies. Haynes puts them all to use in I’m Not There. But if there are all sorts of practical uses for Godardian tactics here, there is also the fact of Godard’s role as a lightning rod for Sixties cultural change, just like Dylan. And like Dylan, if Godard helped to create the Sixties, they also decisively created him. Kent Jones even suggests in a recent essay reviewing Colin McCabe’s Godard biography that Godard’s most enduring artwork is his complex persona.

We’d often go to the movies. We’d shiver as the screen lit up. More often we’d be disappointed. The images flickered. Marilyn Monroe looked terribly old. It saddened us. It wasn’t the film we had dreamed, the film we all carried in our hearts, the film we wanted to make and, secretly, wanted to live.”

At a key moment, I’m Not There transposes these words, spoken by Jean-Pierre Léaud in voiceover in Masculin-Féminin (and drawn from a passage in Georges Perec’s 1965 novel Things: A Story of the Sixties). What’s of striking importance about this text is that it discloses a new cultural attitude about the appetite for cinematic representation, the possibility of “the film we wanted to make and, secretly, wanted to live.” Such a cinema was no longer merely a representation of or “about” people’s lives but rather a tool for directly inventing them. Of course, in today’s digital-Internet-reality-TV world, the image has an unprecedented authority, equal or greater to that which is represented. The negative consequences of this situation were decisively elaborated in Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, the diagnosis of late capitalism’s most recent mutation, the image as commodity, which in trapping our desire blocks and deforms our awareness of the real.

Haynes has absorbed everything wrought by the aesthetic-cultural revolution described by Godard and Debord (and ultimately Dylan), for better and for worse. The voracious power of the image positions conscious artists like Dylan in a uniquely influential place, but corporate and government forces are quick to learn that lesson. The image both liberates and imprisons. This double-sided, positive-negative conception of the image, which is also a positive-negative concept of its political meaning, and its capacity to represent the self, is what inspires what “story” there is in I’m Not There.

Whoever is serving as a Dylan avatar or phantasm at any given point in the film is constantly attempting to outrun the various alternative versions of himself instantaneously being generated in the media-enhanced culture at large, whether in the phenomenon of celebrity, journalistic analysis, or cinematic representation itself—and always at risk of being cannibalized by a relentless, never-ending process of idolatry, imitation, and interpretation.

So what governs and structures I’m Not There is a sense of Dylan as perpetually in flight from banal political interpretation and a celebrity/journalistic culture that seeks to limit, possess, and conclusively define his image. Bruce Greenwood is ominously effective as the reporter/mouthpiece for this process, speaking some of the same accusatory words Brit journalists directed at Dylan in Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back. Greenwood then morphs into a vindictive authority figure modeled on Pat Garrett, hunting Dylan-as-Billy-the-Kid, embodied by Richard Gere. Here, Haynes’s images suggestively conflate biographical and historical myth and Dylan’s own lyrical text, while using music Dylan composed for his 1973 collaboration with Sam Peckinpah on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Billy the Kid is invoked not only as Peckinpah saw him, a symbol of 19th-century Romantic ideas of rebellion, on the run from the inevitable encroachment of 20th-century capitalist forces, but also in terms of the back-to-the-land hippie nostalgia that arose when more radical political hopes were crushed at the end of the Sixties. And these motifs in turn conjure with the facts of Dylan’s disappearance after a motorcycle accident that temporarily removed him from the public eye. But Gere/Dylan/Billy isn’t shot down, he escapes the 19th-century law and finds the 20th-century guitar that once belonged to Woody Guthrie. This moment, with its strikingly “impossible” temporal logic, celebrates the essentially impersonal freedom of art. It’s the image that Blanchett’s avatar will further define in the film’s closing scene when she dismisses the concept of folk singing and replaces it with the idea of “traditional music,” declaring that “traditional music is too unreal to die.”

It’s in the Gere section that the full complexity of Haynes’s structure emerges and starts to assert itself. We realize that each avatar’s destiny is designed to infiltrate the domain of the others, yet no motif is ever completed, finalized, or closed off according to accepted linear models. Historical time, biographical time, mythical time, and the temporality of poetic discourse all reciprocally contaminate, enhance, and transform each other, their imagery cumulatively building and referring in every direction. I’m Not There is assembled from the flights, collisions, intensities, and jumps that constitute these disparate forms of discourse. And so its form is its argument. The film is made out of the very Dylan effect it seeks to describe. It talks the talk and walks the walk.

The audience to which I’m Not There will matter most consists of those concerned either practically or theoretically with the present and future of film, for whom it may mark a pivotal moment. I’m Not There joins Inland Empire, Zodiac, Syndromes and a Century, and I Don’t Want To Sleep Alone as part of a recent and broadly convergent body of work that revises, questions, and sometimes even tosses out narrative fictional structure, in light of our increasingly collective transnational digital culture.

What do these films have in common that I’m Not There pursues with perhaps the most rigorous and consciously elaborate ambition? Critiques of representations of identity and self with a corresponding sense of mutable sexual identity (none of these films are programatically queer and yet none of them are not-queer); narrative fiction incessantly invaded by documentary codes; cinema made with an entirely new post-Internet awareness of the permeability and fragility of all narrative structures; movies that in different ways scan information, in the modes of sampling and remixing. All of these portend an entirely new digital culture as yet impossible to envisage.

What makes I’m Not There the most ambitious of these films is its acute tragicomic-ironic determination to think about the use of this methodology, proverbially linked with postmodernity’s disassociation from political and historical content, precisely to pursue the issue of the representation of political and historical content—or to be more exact, to put the possibility of representing them, in our dangerously ahistorical, apolitical culture, squarely back on the agenda.

Yet as I’ve said, in any easily recognizable or familiar thematic sense I’m Not There is not a political film. At the end of the day, it neither celebrates the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, and the Sixties ethos of sexual/gender freedom nor specifically condemns them for being insufficiently radical or successful. But it is profoundly concerned with—and a demonstration of—the possible impossibility of there being such a thing as a political film. It incessantly questions and critiques how politics appears, reappears, appropriates, and is appropriated, in our culture then and, by implication, now. We are given a chain of hypotheses, models, and allegorical scenes concerning what the political in art ought to be conscious of and worried about.

From the first long moving POV shot traveling from backstage out into the spotlight to the scenes of Blanchett moving among vampiric fans, journalists, and hangers-on (scenes that manage to conflate Fellini, Warhol, Schlesinger, and Pennebaker) to Billy-the-Kid-Dylan catching the same train that the Woody-Guthrie-Dylan rode, Haynes builds a huge circular pattern of images confirming the necessity of the wary American popular artist’s flight from the cultural forces that want to coerce, distort, and possess him.

How can a work not give us politics and yet be so political? In Anti-Oedipus, back in 1972, Deleuze and Guattari assert that “from the moment there is genius, there is something that belongs to no school, no period, something that achieves a breakthrough—art as a process without a goal.” While confronting and scrutinizing the Dylan effect as a component in a myth of our cultural political past, I’m Not There, like all great historical fiction, supplies an image of, and relays back a message about, the undecided fate of our present and future. At the end of his journey, Haynes knows that it may be true that one has to choose between ethics and aesthetics, but he meanwhile retains a tiny margin of political hope by discovering his own distinctive way of choosing not to choose.