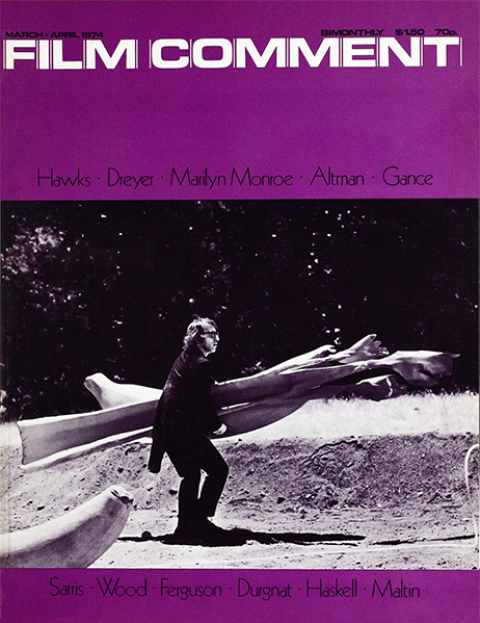

By Molly Haskell in the March-April 1974 Issue

Howard Hawks: Masculine Feminine

Hawks’ view of a world precariously divided between the male and female principles

After a decade of critical rehabilitation, Howard Hawks now stands securely within the triumvirate of classical Hollywood commercial directors: Ford, Hitchcock, and Hawks, with Hawks perhaps playing Adler to their Jung and Freud. His work has been analyzed in terms of a consistent oeuvre that sets forth—in the alternating heroic and mock-heroic terms from which it is inseparable—a vision of man as a ramrod of courage and tenacity, and a squiggle in the margin of the universe. The intuitively American quality of Hawks’ films expresses itself in themes of male-female competition, sexual inversion, and the struggle between adolescence and maturity for a grown man’s soul.

From the March-April 1974 Issue

Also in this issue

Once one has accepted the interdependence of comedy and tragedy in his work, it is hard to miss the deeper implications: the picture of man poised, comically or heroically, against an antagonistic universe, a nothingness as devoid of meaning as Beckett’s, but determined nonetheless to act out his destiny, to assert mind against mindlessness. In his tales of man struggling against the environment; in his odysseys (for even when the locales are stationary, the films are journeys) of fraternal bands in remote places with only themselves to rely on, Hawks’ vision is one of man (and woman) stripped of ecclesiastical significance, self-created to the point where not only God but mothers are absent, and evolved to a precarious ascendancy over nature and animals which he must fight to maintain.

Because of the remarkable consistency of Hawks’ films even from the beginning, and the degree of artistic and stylistic control he exercised over almost all of his projects, we are likely to underestimate the evolution in his work, particularly in his vision of women, and his mellowing attitude toward “the group”—at first all-male, and later marked by a relaxation of the criteria of admission to include freaks and outsiders, cripples and women. There is a feeling for character in his films that, while rooted in sex-role expectations, goes beyond these to the reversals that are, as much as the mixture of comic and tragic moods, the source of humor and peril in Hawks’ view of a world precariously divided between the male and female principles.

The masculine and feminine instincts are locked in perennial combat. A consummately Hawksian scene is the sexual duel that begins His Girl Friday, a brilliantly choreographed and edited sequence in which the balance changes every second: between the characters, as first Cary Grant, then Rosalind Russell gains the upper hand; between the prevailing strategy, as each uses “masculine” tactics (physical assault) and “feminine” wiles (pleading and wheedling); and in the alternating tone of the scene, from emotional (close-ups) to comic (medium shots). Beneath the vigorous and sometimes-willed virility of the action pictures, Hawks’ genius consists of bipolar impulses; thus his ability to understand, and portray, in men, the temptation to regress, to succumb, to be passive, to be taken care of (Cary Grant in Bringing Up Baby and I Was a Male War Bride), and, in women, the opposing need to initiate, act, dominate.

His Girl Friday

The perilousness of Hawks’ world, the sense of a cosmic (and comic) disequilibrium, comes from the problematic nature of sexual differentiation, an issue that is never completely resolved. But there is an evolution: the “feminine” side that is viewed by the young man as dangerous or debilitating (the “weakening” effect of the emotions) is gradually welcomed as a crucial element in adult men’s lives; and the aggressive side of woman becomes less and less incompatible with femininity.

The “Hawksian woman” does not really blossom until the late Thirties. Though often found in Hawksian situations, the women of his Twenties films are closer to the general stereotypes prevailing in silent film than to his own gutsy, deep-voiced (voice being important to Hawks’ women), modern, and very American heroines. His first film, The Road to Glory (made in 1926, and no relation to his 1936 war film), starred May McAvoy in a tragedy about a blind girl. Possibly Hawks’ most downbeat film, it indicates something of his mood and bent before he determined that tragedy “wasn’t what audiences wanted to see, so, in my next film, I changed the tone.”

The silent films, callow and occasionally charming, have none of the qualities we associate with the later Hawks. Only A Girl in Every Port has sustained more than marginal interest. The plot, in which a beautiful circus entertainer threatens to break up a beautiful male friendship, presents the prototypal triangle of the Hawks male adventure film; but the movie’s high reputation with the French seems based on the presence of Louise Brooks rather than any inherent virtues in the film itself. And even Brooks is far less interesting here than in her films with Pabst, or even her non-Hawks Paramount films. Hawks was not really at home with the femme fatale. Indeed, he was at ease with the overtly sensual woman only when, as with Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not, or Angie Dickinson in Rio Bravo, he could play around with their sensuality, suggest a kind of gamesmanship that was the equivalent of a man’s self-deprecating bravery.

The melodramas of the Thirties present the ideal of male heroism and self-sufficiency in its purest form: men at war, facing death daily as fliers (Dawn Patrol, Ceiling Zero), soldiers (The Road to Glory), torpedo boat pilots (Today We Live), lapsed heroes trying to redeem themselves or expiate guilt by taking a friend’s place on a suicide mission; men engaged in high risk commercial ventures like tuna fishing (Tiger Shark), commercial aviation (Only Angels Have Wings), auto racing (The Crowd Roars), organized crime (Scarface), taking outrageous risks without questioning the ground rules, attracted by what Robin Wood has called “the lure of irresponsibility”—men ruined, separated, betrayed, goaded to their death by women.

Dawn Patrol

In the framework of the early action films, the woman who disrupts the friendship of two men, or precipitates their downfall, is more symbolical than real: a projection of the grown-up world—of civilization, the home, the family, adult responsibility—that is hateful to the adolescent and inhibiting to the free play of his fantasies of adventure and omnipotence. But the women to whom Hawks eventually gravitates are not “killjoys,” not hearth-and-home types, but women who (for better or worse, and feminists are divided on this point) could get along in a man’s world. Women at this early stage (and in this Hawks is no different from other male artists—Jean Renoir, for example) are fantasy figures who conveniently bear the brunt of youth’s disillusionment.

Significantly, the femme fatale in The Dawn Patrol (1930), Hawks first sound film, is not even present in person. Her malfeasance—a rupture in the friendship of flight commander Neil Hamilton and his second in command Richard Barthelmess—has been accomplished offscreen. The “woman problem” is adduced to intensify the existing conflict between the man in authority who must send fliers out to their death each day and the intermediary who pleads for mercy. The retreat to the all-male world, as well as the projection of woman as an evil force, suggests a fear of the feminine side of oneself—a side that is especially, and delightfully, prominent in Hawks. Manny Farber astutely commented on “Hawks’s uncelebrated female touch,” and it is as much responsible for the mixed moods of his films as for the graceful movements of his actors.

In The Dawn Patrol, there is already the strong sense of contrast between the two worlds: the exhilaration and danger of the action world, and the comforting womblike enclosure of the base. But the relation between the two is more paradoxical: for if the action world entails the greatest risk to life, it also provides, in the submergence of the self in a womanless world, a cathartic release, while in the interior world, for all its physical security, there is greater friction between people, in relationships that are complicated, explicitly or implicitly, by women.

Tiger Shark

The two worlds are more deftly threaded together in Tiger Shark (1932), where the extraordinary fishing sequences are directly related to the tragic Ahab-like character of Edward G. Robinson, and the rivalry over the woman (played by Zita Johann) culminating in Robinson’s death coincides with that other Hawksian theme of the superiority of the “whole” man over the mutilated one. Robinson—old, unattractive, and without an arm—loses the girl to the young and handsome Richard Arlen (just as Robinson loses Miriam Hopkins to Joel McCrea in Barbary Coast) in a ruthless application of the law of survival in which, as Andrew Sarris has pointed out, woman is the equivalent of God and nature in arbitrating the process of natural selection. And yet, once again, Hawks seems to be projecting onto woman something that he himself feels a distaste for the ugly, the maimed, the unfit. In The Big Sky (1952) the fingerless Kirk Douglas must lose the Indian princess (Elizabeth Threatt) to Dewey Martin; but it is Douglas himself, and not the girl, who makes this decision, sending Martin back in the end to remain with her on the reservation.

The bond between brothers or brother-surrogates is the bond of emotional or blood kinship (and thus the brother and sister in Scarface are analogous to the brothers in The Crowd Roars)—a rapport between people who understand and are at ease with each other instinctively rather than by intellectual or emotional effort, who come together without the tension created by sexual attraction/antagonism. The girl in Ceiling Zero hugs her confederate, Pat O’Brien, and shakes hands with her boyfriend. Hawks directs scenes of action and robust affection with the utmost fluidity but is awkward in love scenes (like the culminating one in Barbary Coast, in which he cuts nervously between, and away from, Hopkins and McCrea). But when the sexual antagonism is confronted, or transmuted into the artful chaos of the comedies, it creates an emotional field that is in some ways richer and more dynamic than the relatively straightforward simple, and overt expression of love among “likes.”

Like the Platonic (as opposed to physical) homosexuality that Robert Graves criticizes in The White Goddess, or the incestuous pull that D.H. Lawrence finds in Poe, this “love affair between two men” is ultimately a form of narcissism the self-fixation of man unable or unwilling to acknowledge the Other, or take the necessary steps (ranging from an acknowledgement of dependency to a willingness to be depended upon) to understanding this creature who plays the moon to his sun. Both the glorification of the two brothers in The Crowd Roars and the shared doom of Paul Muni and Ann Dvorak in Scarface, are a means of isolating them from heterogeneous humanity.

In Ceiling Zero—with James Cagney as the daredevil flier and Pat O’Brien as the boss enmeshed in bureaucracy—the world of action and enclosure, of women and men, of comedy and tragedy, are integrated to an unusual degree even for Hawks. Cagney, cocksure and irresistible, a flier of the old order that Hawks admires, fakes illness to stay behind and date a cute girl flier named Tommy (June Travis). One of the first examples of the Hawksian woman, the excitement she generates, as a bright and active woman as obsessed with her job as any man, is beyond the dimensions of her role. In an even smaller part, Isabel Jewell, as one of the flier’s wives, begins as a conventional nag and killjoy but turns, with her husband’s death, into a figure out of Greek tragedy.

Bringing Up Baby

All this zaniness—or so it seems in the women Hawks chooses—is something of a defense mechanism, a cover for an underlying vulnerability. Bringing Up Baby’s Susan and The Twentieth Century’s Lily Garland, so headstrong and self-reliant, are socially and sexually insecure. (Ann Sheridan’s Catherine Gates in I Was a Male War Bride, is professionally competent, but a sexual dunce.) Susan and Lily don’t know how to “play games”; and in allying themselves with the forces of nature, in hurling themselves at the opposite sex like hurricanes, they increase their chances of survival in a man’s world. But the moment they turn into pure whimsical aggression their targets reveal themselves to be not male supremacists, stalwart and secure, but specimens of the opposite sex as faltering and insecure as they are. In the safari metaphors of the comedies—Paula Prentiss tracking down and exposing Rock Hudson’s phony fisherman in a California hunting resort in Man’s Favorite Sport?; Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant ploughing up a lawn in search of a fossil (and Grant winding up in a net); the lexicographers in Ball of Fire entangling themselves in the briars and brambles of Sugarpuss O’Shea’s slang underworld; Grant and Sheridan on their circuitous mission through Germany—the bravado and fear and sexual uncertainty of the American dating ritual are comically exposed.

Grasping the principle that a fundamental sobriety is essential to comedy, Hawks intensifies his characters’ seriousness until it becomes a kind of maniacal self-absorption, the obsessiveness that is the madness of the screwball characters. The breakneck pacing of the comedies comes from the fact that in a sense no one is sane. Cary Grant’s paleontologist is, in Hawks’ view of the pure scientist, as abnormal as Hepburn’s country club playgirl. Rosalind Russell is headed for suffocation and slow death in her prospective marriage to Ralph Bellamy; Ginger Rogers’ understanding wife, in Monkey Business, is full of hidden resentments which emerge, like truth in alcohol, once she has taken the drug. Two madnesses must collide to shake the male-female antagonists into some kind of awareness of each other, of themselves, and of a mutual destiny that, if problematic, is definitely not that of the average suburban couple.

Another comparison that strikingly illuminates the uniquely Hawksian view is the difference in treatment between Red River and Raoul Walsh ‘s version of what is basically the same story in The Tall Men. In Walsh’s relaxed attitude towards women, some might find a more mature vision of the sexes. The Jane Russell character is more of a companion than a threat, and even the distracting influence she represents is treated with affection rather than resentment. She is bawdy, sexy, and tough. And yet it is the women in Red River—Coleen Gray as Fen, the woman left behind by Wayne, and Joanne Dru, as Tess, the Fen-surrogate who falls in love with Matthew (Montgomery Clift) who are crucial in the elaboration of the intense primal conflicts that make the Hawks a greater film.

Only Angels Have Wings

In the Forties, there is a detente with women—prefigured, perhaps, in the reconciliation which concludes Only Angels Have Wings, in which Grant, having lost his closest friend (Thomas Mitchell) is united with Jean Arthur, and the close mother-son relationship of Sergeant York (1941), with Margaret Wycherly as one of the only major mother figures in all of Hawks. There is still, in Only Angels Have Wings, a strong streak of self-pity disguised as tough indifference, but within the fogbound base of the civil aviators in South America, one of Hawks’ moodiest and most romantic fantasies unfolds. Rita Hayworth is a more sympathetic version of the femme fatale, but Jean Arthur, lacking the worldly independence of later heroines in the same situation, is too craven in her availability; she makes one wince in embarrassment to the tune of woman as second fiddle. The use of woman is again symbolic—she is the “emotional” element—so that although the film’s cast and setting prove almost irresistible, one almost prefers the all-male world of Air Force (1943) in which Hawks takes the ethic of the group—and the submergence of individuals in a common purpose (the adventures of a B-17 crew during and after Pearl Harbor)—to an almost Fordian extreme, the point at which the fliers become one with their mission or, in this case, their machine.

It was Hawks’ idea to pair Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946), and although he must be credited as the originator of their best roles, they did bring something of their own to the films, a personal chemistry, to create the one truly and magically equal couple in all of Hawks’ cinema—a rarity in any art form where the personality of one person, the artist, necessarily dominates his sexual opposite. This is not to say that Bacall somehow escapes being a male fantasy, but she pulls her own weight—verbally, professionally, sexually—to a much greater degree than most movie heroines. She’s tough, smart, feminine, neither virgin nor whore, and if she makes no bones about loving Bogey, she somehow gains the upper hand by having the confidence to be open and funny and honest. She not only isn’t a threat to male supremacy but, in To Have and Have Not, she represents the alternative—heterosexual pairing of equals—that is, finally and unequivocally, both adult and fun.

Like so many of those behind-the-scene accidents of chemistry whose effects on movies we can never fully know or measure, her success as a character can probably be attributed to Hawks’ dislike for Bogart, and consequent identification with Bacall. “You are about the most insolent man on the screen,” Hawks is quoted as having said to Bogart before The Big Sleep, “and I’m going to make a girl a little more insolent than you are.”

Thus whereas before the Bacall-Bogart movies, and even after them (in The Big Sky, Rio Bravo, and El Dorado), the woman would take a back seat to the friendship between two men, in To Have and Have Not they are completely on a par, her work corresponding to his. While Walter Brennan, as the loyal but enfeebled sidekick, will reappear in the later films, the peer comrade whose later counterpart is Dean Martin and Robert Mitchum, is here played by Bacall.

To Have and Have Not

The interests of melodrama and comedy are perfectly fused in the sexually pregnant atmosphere of The Big Sleep, beginning with the initiation of Marlowe into the hothouse-greenhouse world of General Sternwood, a scene that comes straight out of Raymond Chandler. To the assorted dames of the author, Hawks added a few, creating the sense of a world run and manipulated by women (the two Sternwood sisters run their father, Dorothy Malone runs a bookstore, Peggy Knudsen fronts for the gangsters, and an unbilled woman runs a taxi!) that would recur only in Rio Lobo (1970).

Hawks was ahead of his time, not only in a certain cavalier indifference to plot connections, but in his sophistication about drugs (in the spaced-out Martha Vickers character, and in plot mysteries which a drug-based operation explains) and homosexuality (Bogart does a “fairy” imitation, and back in Bringing Up Baby Grant actually used the word “gay”). Such references, so apparently glib, are more central to the themes of Hawks work than their casual introduction would indicate, to the sense of complex and conflicting character tendencies and the struggle to maintain an equilibrium that is felt less as a natural inclination than as a social and moral necessity. Thus, however simple Hawks’ idea of maleness, or femaleness, may seem to a modern, liberated, technological society, it is a moral, existential view; and if the professionalism that becomes the “solution” to character is simple, the urges behind it are not.

That Hawks feels at once the difficulty and the importance of heterosexual coupling becomes explicitly clear in The Big Sky when after the trapping expedition Douglas sends Dewey Martin back to his Indian wife. The dialectic between emotions and obligations, between the natural inclination and the socially-correct resolution has never been expressed in quite such mutually exclusive terms. A situation which Lubitsch might have concluded with a triangular “design for living” is resolved in a coercive either/or manner to signal a young man’s coming of age, weaning himself from a father figure who has exercised far too dominating an influence on him. The act of the will by which he fulfills both his conjugal and filial debt becomes, at least theoretically, a triumphant synthesis. The Indian princess, denied the power of (English) speech, is the most physical of Hawks’ heroines, and establishes (and secures) her identity not only by her expertise as a guide, but by keeping her husband on the reservation rather than following him as chattel in his world.

From The Big Sky onward, including films like Land of the Pharaohs and Hatari!, the group is more of a mixed proposition, and the struggle itself becomes more communal rather than individual. The youthful all-male platoons and patrols give way to heterodox collectives of widely varying ages, who are engaged in a primal struggle to assert themselves against an indifferent nature. Through his John Wayne surrogate, Hawks begins to delegate authority to the younger generation—or in Red Line 7, 000, to turn the film over to them. It’s a long way from Tony Camonte’s egocentric motto and the driving, jabbing, angular world of Scarface to the pastel end-of-day (but no less violent) world of Rio Lobo, with a wounded John Wayne hobbling along, supported by a pretty but unmemorable ingénue. But before this dissemination of power, there is one last gunfighter duet—only the gunfighters are gold-diggers, and they aren’t men, but women.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which seemed completely immersed in Fifties garishness when it appeared in 1953, looks somewhat more skeptical today—a musical that is as close to satire as Hawks’ films ever get on the nature (and perversions) of sexual relations in America, particularly in the mammary-mad Fifties. As the Dean Martin and John Wayne of the transatlantic liner, Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell have not only the biggest knockers in the West (a monumentality to which the ship’s passengers pay hushed tribute as they pass by) but the best relationship in the film. Russell defends Monroe against her critics, and Monroe loves Russell in return. The men in their lives consist of a rich old sugar daddy (Charles Coburn, in a switch from his customary benevolent paternal roles), a precocious child (George Winslow), an effeminate fiancé (Tommy Noonan), and an ostensibly-normal suitor (Elliott Reid) who turns out be a spy.

Hawks totally transforms the original—a Broadway play adapted from the Anita Loos novel—by making a mythic link between greed and sexual freakishness, and creating a whole world that revolves on a principle of unnatural sexuality. There is the magnificent gag with the porthole in which Monroe’s protruding head perches atop an elongated blanketed torso concealing little Winslow. He croaks complaints while Coburn caresses his extended hand and Monroe tries desperately to “control” her body, in a hilarious three-way image of sexual short-circuitry. The other biting, brilliant commentary on sexual cross-purposes is, of course, the song number in which Russell, surrounded by a corps of bodybuilding athletes too intent on toning themselves up to notice her, sings “Is there anyone here for love?”

The debate as to whether Russell represents “normal” or excessive sexual drives is answered in the ambiguity with which Hawks perceives Monroe and Russell as filling their roles as sex goddesses. Indicating his awareness of their quintessentially Fifties “front,” Hawks has pointed, in interviews, to the irony of Russell marrying her high school boyfriend and settling into domesticity (a condition she has recently, and perhaps not so illogically, exchanged for religious fanaticism), and of Monroe being a wallflower at a party with no one to drive her home. This sense of incongruity is felt at the heart of the sexual exaggeration and masquerade. In a funny but truly pessimistic ending, Russell finally gives up on finding anything like a normal relationship and joins Monroe as a mock-blonde, opting for gold over diamonds, securing her future against a sexist tradition which will either avoid her, or leave her eventually for a younger version of herself.

It is a tradition to which Hawks himself is not altogether immune, not just in the ethic of his films, but in his choice of actresses, who reflect the sexual taste of the man as much as the professional criteria of the director. Men like Grant and Wayne appeared over and over again, accumulating character lines, gaining resonance with familiarity, being allowed to grow old. But, with the exception of Bacall, his women stars appeared only once, carrying the implication that having once served, a woman had had her day and, like the aftermath of a love affair, was now “used.” Hawks gravitated to a certain kind of woman and coached her to conform to a taste for a woman who would look young but seem older. Thus if Angie Dickinson, sensual and active, womanly and direct, is one of his most exciting heroines, she is also the impossible dream of male fantasy, being at once the blossom and the fruit, ripe and yet virginal, sexually aware and yet somehow newborn for the hero. An active woman, she is suddenly willing to wait as he works things out with the men who occupy first place in his life. She brings her independence only as far as the threshold of a relationship, as a sort of gift, and no further. If Rio Bravo is a movie one loves and returns to like an old friend, isn’t this partly because there is something clubby and reassuring in the male enclosure, where the dimension of risk—the real risk, created by women rather than “bad guys”—has been artificially excluded?

Hatari!

Hatari! (1961) will show a commune of men and women engaged, under John Wayne’s guidance, in big-game hunting. The youthful unknown cast of Red Line 7000 will work out their own definitions of professionalism and love in a world that seems devoid of most of the Hawksian graces. The later westerns of the Rio Bravo trilogy—El Dorado (1967) and Rio Lobo (1970)—show Wayne aging and edging toward the periphery of the action, and the Rio Lobo community, composed largely of females, becomes the protagonist, redefining itself as the film progresses. But Rio Bravo presents Wayne as the apotheosis of the Hawksian hero, older, still strong but requiring help (with that very need becoming the instrument of salvation for his weaker colleagues), generous, firm, a little foolish about women, but coming to terms with his prejudices by recognizing that a woman can act with the resolve and daring of a man, and thus accepting his “weakness”—his need for her—through her own “masculinization.”

The charge leveled by feminists that Hawks’ women must model themselves after men to get their attention is largely true. For one thing, his men are somewhat retarded in the process of learning how to deal with women. But the behavior of his tomboys and bachelor girls is also an explicit challenge to traditional stereotypes of what a woman is and should be. Their aggressiveness arises from a variety of motives and instincts, from ambition, energy, intelligence, sexual insecurity, and from a frustration, perhaps, at being so long excluded from the world of action and camaraderie and non-sexual love that Hawks’ cinema celebrates.

For better or worse, the maternal (childbearing and nurturing) side of woman—so beautifully evoked in Ford, and so blindly and exclusively honored by most male artists—is foreign to Hawks. Its loss is felt not in the most obvious area of character invention and the absence of older women, but in some subtler, more shadowy region of the sensibility. A mature acceptance of the dual principles of life in which woman is complementary to man would undoubtedly have given Hawks a more complete and stimulating vision, a richer and more mystical view of the world. But perhaps it would have removed the sexual tension, and the tension with nature (as Mother Earth) that is at the heart of Hawks’ work, and that activates the genius of an artist who has been at once the most knowing and naive, the most elegant and the most awkward, the most male and female, the most American of directors.